The recent exhibition of French Impressionist masterpieces at the National Gallery of Victoria, replete with ethereal tableaux of sunlit seascapes, perfumed gardens, and the fleeting splendours of modern life as captured by Monet, Renoir, and their contemporaries, has not only reaffirmed the enduring allure of this revolutionary artistic movement but has also, perhaps unwittingly, rekindled a latent question: where is the Hellenic presence in this radiant dialectic of light and colour? Among Monet’s translucent visions of Antibes, Renoir’s effulgent Mediterranean bays, and Cézanne’s sun-scorched Provençal orchards, there pulses a sensibility kindred to the Aegean, one that intimates, though never articulates, a Hellenic gaze. One leaves the gallery imbued with a sense of something glimpsed but unspoken, something familiar yet absent, a silence wherein the Greek response to the aesthetic revolution of Impressionism ought to have been inscribed.

This omission, however, is not the result of a historical void but rather of historiographical oversight. For Greece, emerging from the crucible of revolution and imperial unravelling in the nineteenth century, did indeed cultivate its own Impressionists, painters who, though inspired by the same Parisian ethos of optical immediacy and atmospheric sensation, articulated through their art a profoundly indigenous engagement with light, place, and national identity. Greek Impressionism did not proceed as a passive imitation of foreign aesthetic currents, but as a luminous act of reappropriation, in which the palette of the West was applied to the particular topography of Hellenic experience.

To comprehend the emergence of Greek Impressionism is to peer into the shifting soul of a nascent nation. Following the hard-won independence from Ottoman dominion, the modern Greek state found itself engaged in an epic endeavour of cultural reclamation. Visual art, alongside the reconstitution of language, education, and public ceremony, became a pivotal vehicle for asserting the continuity of modern Hellenism with its classical antecedents. In this context, the prevailing artistic orthodoxy was Neoclassicism, upheld with near-doctrinal rigidity by the so-called Munich School, whose exponents, trained in the ateliers of Germany, populated their canvases with allegories drawn from antiquity and tableaux exalting the Greek War of Independence.

Yet as the nineteenth century waned and the sun of the twentieth began its slow ascent, a younger generation of Greek artists began to resist the constraints of didactic historicism. Many turned their eyes toward Paris, that fecund crucible of modern art, where they encountered Impressionism in full flower. There, in the cafés and salons of the Left Bank, in the gardens of Montmartre and along the Seine, they came into contact with a visual language that privileged sensation over symbol, immediacy over monumentality, and light itself as both subject and medium. What they beheld was not merely a technique but a revelation: a way of painting the world as it was seen and felt, not as it was remembered or codified.

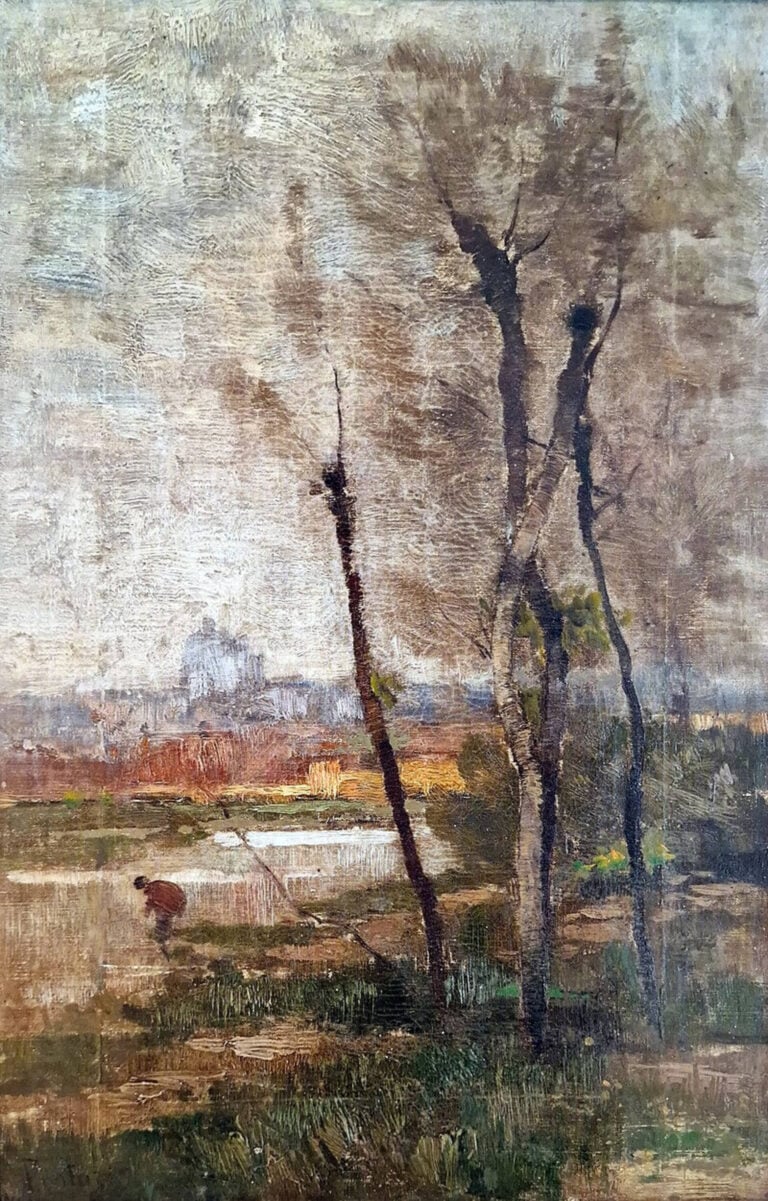

Nevertheless, the Greek artists who absorbed the tenets of Impressionism did not do so without discernment. Where the French had turned their gaze upon the ephemeral pleasures of the city, its boulevards, cafés, and leisure, the Greeks brought their focus to the enduring rhythms of the countryside, the insistent brilliance of the Aegean sun, the play of shadow across whitewashed stone, and the repose of domestic life. In so doing, they created an art that was at once modern and rooted, international in its methods yet profoundly Hellenic in its substance.

The ideology underpinning Greek Impressionism is best apprehended not as a manifesto, for none was issued, nor as a school, for no formal cohesion existed, but as an ethos, a mood, a chromatic attitude toward the world. It is an art that seeks to render the ineffable, to depict not merely what lies before the eye but the shimmer of memory, the tremor of place, the warmth of afternoon falling upon a marble sill. It constitutes a deliberate turning away from the heroic and monumental toward the quotidian and atmospheric, affirming in each stroke of the brush a new vision of Hellenic identity grounded in lived experience rather than mythic abstraction.

This reorientation did not signal a retreat from the national idea, but rather a subtle refinement of it. In depicting a shepherd beneath Mount Penteli, a woman in repose beneath a fig tree, or the cerulean undulation of a fishing boat in an island harbour, the Greek Impressionists were not abandoning the narrative of nationhood; they were enriching it, endowing it with intimacy, with light, with breath.

Among these artists, the figure of Periklis Pantazis stands preeminent as the most faithful, in both technique and temperament, to the spirit of the French Impressionists. Born in Athens and trained in Paris under the tutelage of Gustave Courbet and Gustave Boulanger, Pantazis later established himself in Brussels, where he fell under the influence of Belgian realism and the avant-garde. His oeuvre, though tragically curtailed by premature death, reveals a masterful command of atmospheric nuance.

In his celebrated Woman with a White Cap, Pantazis evokes the quiet poetry of domestic interiority. The figure, her features softened by a haze of afternoon light, is rendered with a lyricism that rivals the tender moments of Degas or Berthe Morisot. Similarly, his Still Life with Fish transcends its humble subject through a vibrant choreography of colour and form, transforming the ordinary into the sublime. In Pantazis, the Mediterranean palette fuses with northern technique to produce something entirely original, a luminous hybrid of place and method.

Another towering presence is that of Konstantinos Parthenis, whose idiosyncratic vision straddled the realms of Impressionism, Symbolism, and metaphysical introspection. Born in Alexandria and educated in Vienna, Parthenis was both painter and philosopher, seeker and seer. His early works, such as The Harbour of Corfu, evidence a delicate Impressionist brush, but one inflected with spiritual yearning. In The Garden of the Nuns, one detects not only the ambient interplay of light and foliage, but also a deeper allegorical resonance, as though the scene were transfigured by the contemplative gaze of Byzantine iconography.

Parthenis’s engagement with Impressionism was never merely ocular. It was spiritual, an attempt to reveal the numinous through the visible, to paint what light suggests but does not declare. His subsequent turn toward modernist and religious imagery should not obscure this earlier period, in which his brush rendered not the materiality of the world alone but its metaphysical aura.

The Paris-based Iakovos Rizos presents a more urbane dimension of Greek Impressionism, one oriented less toward landscape than toward interiority. His paintings, often of women engaged in quiet reverie, combine the compositional elegance of Manet with a distinctly Mediterranean intimacy. In Young Woman Reading, a shaft of sunlight falls gently upon the subject’s lap, illuminating not only the folds of her gown but the texture of silence itself. The restraint of Rizos’s brush, more refined than broken, suggests an Impressionism tempered by classical clarity.

Rizos’s contribution lies in his affirmation of the domestic and the feminine as worthy subjects of high art, and in his capacity to suffuse these interiors with a light not merely physical but emotional. His art is one of stillness and suggestion, of elegance suffused with quietude.

In Thalia Flora-Karavia we encounter a singular figure, not only for being a woman in a predominantly male artistic world, but also for her vast geographical scope and ethnographic sensitivity. Educated in Munich and widely travelled throughout Asia Minor, the Balkans, and Egypt, she applied Impressionist technique to subjects far removed from Parisian boulevards. In Women of Cairo, she depicts with unflinching warmth and acuity the cultural plurality of the Levantine world, her palette fluid, her brush unburdened by exoticism.

Flora-Karavia also distinguished herself as a war artist, capturing the human cost of conflict during the Balkan Wars. Her swift sketches of soldiers and refugees, rendered in pastel or oil, combine journalistic immediacy with painterly compassion. In her hands, Impressionism becomes a mode of witnessing, of attending to the overlooked and the endangered with luminous fidelity.

Georgios Roilos, initially an adherent of the academic Munich style, underwent a gradual transformation that brought him into the orbit of Impressionism. As a pedagogue at the Athens School of Fine Arts, he played a pivotal role in disseminating new visual approaches to a younger generation. His painting The Conversation exemplifies his mature synthesis: two women beneath a pergola, the dappled light filtering through vine leaves onto their garments and skin, the moment unremarkable yet imbued with a profound psychological resonance.

Roilos, more than a painter, was a transmitter of vision, a midwife to the evolving eye of Greek art. His legacy lies not only in his own canvases but in the sensibility he cultivated among his students, a sensibility receptive to light, to nuance, to the quiet profundity of everyday life.

Greek Impressionism never coalesced into a movement in the formal sense. It issued no polemics, no manifestos. Yet its impact upon the cultural imagination of Greece was immense. It signalled a shift from the monumental to the intimate, from the allegorical to the atmospheric, from the fixed icon to the ephemeral impression. It offered a new visual idiom through which Greece could contemplate itself, not as the static heir of antiquity, but as a living, breathing presence in the modern world.

The legacy of the Greek Impressionists lies in their capacity to refract light not only through pigment but through history, to allow the nation to behold its own landscape, its own people, its own interior world with fresh and unguarded eyes. Their paintings are not merely aesthetic artefacts. They are meditations on presence, on memory, on the profound resonance of the seen and the felt. TAnd thus, while the Mediterranean may have shimmered evocatively through the masterworks of Monet and Renoir, glimpsed as a luminous abstraction or as the distant promise of warmth, it is through the canvases of Pantazis, Parthenis, Flora Karavia, Rizos, and Roilos that the much vaunted Greek light is not merely remembered but enriched, not only celebrated but deepened. In their hands, it becomes not a borrowed motif but a native radiance, rendered with intimacy, suffused with ancestral memory, and imbued with an enduring Hellenic eloquence.