Cornelius Castoriadis reflected on humans. He decided that the role of each person in the social-historical context is essential.

Castoriadis was himself in awe of ideas. Ideas are what, in time, brought about his faith in humanity. He was the Greek–French thinker who honoured our Hellenic ancestors’ philosophical enquiries.

Castoriadis lived in three cities: Constantinople (Istanbul), Athens, and Paris. Born in Polis in 1922, he grew up in Athens, where he studied law and philosophy, and then left for Paris at the age of 23. He lived and worked in Paris until he died in 1997.

Castoriadis was contemplative from a young age and was a voracious reader. In Athens, his house—according to author Mimika Kranaki, a friend of his youth—was “located behind the Metropolis, the main Cathedral of Athens.”

The size of this temple would later underscore his thinking against God and all religions. Castoriadis grew up “in the shadow of God.”

In this house, at the age of six, he “attempted to kill himself” by grabbing an electricity cable with wet hands.

Castoriadis was interested in a wide range of intellectual pursuits. He began to read early and learned how to promote thought. Max Weber’s work on bureaucracy inspired him. Karl Marx’s texts were also read by him in his home. This is where he returned after school and later after attending lectures by the neo-Kantian philosopher K. Despotopoulos at university.

He was also a brave young man. At the age of just 13, he lost all his hair. His mother, Sophia Castoriadis, became mentally ill and, tragically, died a few months later. His father, Caesar Castoriadis, made sure that he did not miss out on anything—they even had a phonograph in the house. His father, a Voltairean, did not allow his son to stay up all night to complete the written punishment that the school had imposed on him, which almost caused young Cornelius to grab the wet cable, as mentioned above.

At the same time, the loss of hair gave him strength at a very young age. His friends bullied him by calling him “globos” or “light-globe.” In his first steps, he recognised the power that “small circles or small groups” have in the evolution of history and ideas.

Castoriadis’s Odyssey

The real Odyssey began in 1945: Paris—with its libraries, its students, the groups that write history, and the ‘biggest A’ in the world.

In Paris in 1948, Castoriadis, along with Claude Lefort and other friends and partners, created the group and magazine Socialism or Barbarism (1949–1965) – a forum and often a battlefield of ideas. In it, under various pseudonyms, Castoriadis published a mass of theoretical texts.

He also worked as a professional economist for the OECD, and his writings were another reason he used pseudonyms, such as Paul Gardan. Paris is the city that emboldened his thinking. Sigmund Freud influenced him decisively, and through Freud’s work, he recognised what was missing from Marx: the human subject.

Marx underestimated the importance of the individual—and the moral dimension. Castoriadis’s work is a continuous critique, open to critical interpretation. The two pillars of Castoriadian creation are: the imaginary institution of society and autonomy. He contributed to many areas of thought.

A personal acquaintance

I knew him in person. We exchanged letters, and I spoke to him on the phone. I sent him the first letter when I was 18 years old, and he replied. His kindness was noteworthy. He was extremely polite in our meetings—in his office or when we went for a swim. He radiated light and had a sophisticated sense of humour and wit.

With him, it was impossible not to smile or laugh at something he would say or a passing remark. He was also an active man who did much in a single day. I saw him swim in the Greek seas—he could swim from island to island in the Aegean. I cannot forget the image of him swimming.

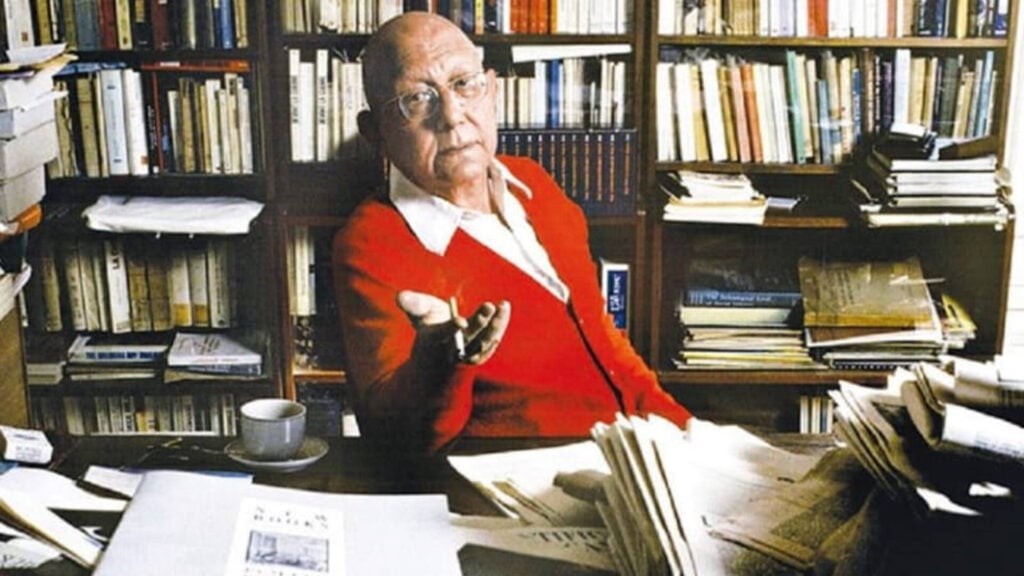

He moved his hands a lot—not in the water, but mostly out of it. His thought had an experiential depth and ethos that I saw with my own eyes.

Castoriadis, exuberant in expression and strong in spirit, was constantly evolving. Affairs, gambling, cigars, whiskey, the stock market, and songs with a sad theme—moirologia, traditional Greek laments for the dead—played their part.

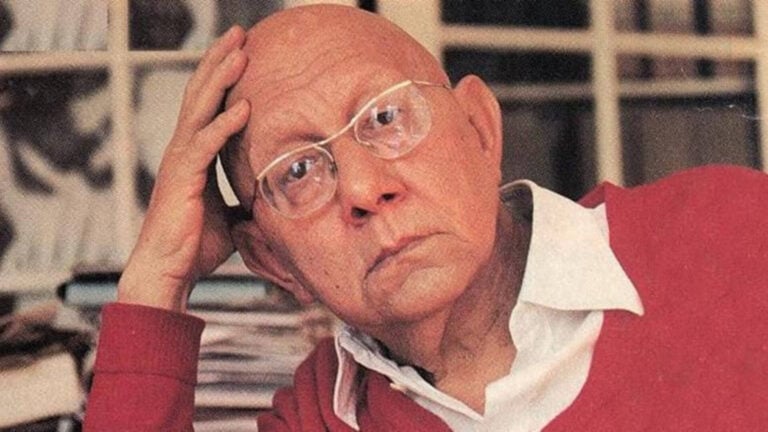

His strong personality ensured his path was a lonely one, outside the intellectual fashions of Paris. He stood out.

Castoriadis loved dialogue. He loved ideas, and once told me when we met in his office:

“When a new idea comes to my mind, I feel a great surprise.”

His awe for ideas led him to reflect on the uniqueness that every human being deserves—the uniqueness of, say, the militant Nikitaras, hero of the 1821 Greek War of Independence, who shouted to the Turks: “Persians, let’s fight!”

The only ‘theory’ Castoriadis left behind was his imprint as a human being. An imprint that marked those who knew him up close.

Exuberant and powerful spirit

When asked how he knew that a cow appearing before them was wild, he answered, “It has an expression on its face.” (It was, apparently, the peculiar breed of cow from the Greek island of Tinos.)

He impressed the listener and imparted knowledge hand-in-hand with humour.

How did I find myself in the car, driven by Castoriadis himself, in 1996? This is the personal testimony I developed in the humble book of 2014.

The rare gift of humour that the ‘atheist Castoriadis’ had is like the sharp stings you receive when you read him. He had a sense of humour—and a sense of humanity, as I said.

And those bites of humour make you say, “The West—Hellenism—gave birth to a genius.”

The legacy of Cornelius Castoriadis is priceless. And although we are separated from ancient Greece by 130,000 weeks, Castoriadis was, as I often say, “an ancient Greek in Paris.” A person dies at some point, but his ideas remain standing. I believe he will continue to inspire… just like the Parthenon.

The thoughts published here were delivered in a lecture in Greek on Sunday, by Dimitris Eleas on October 13, 2024, at the Institute of Research and Study Thucydides. An early manuscript was read by the Australian intellectual and professor, Mr. Vrasidas Karalis, whose apt observations honour him in particular.

*Dimitris Eleas is a political scientist, writer and researcher living in New York.