A few years ago I made a long anticipated trip to the beautiful Island of Samos. I had always wanted to visit its museums and archaeological sites, as well as the memorials to its role in the Greek War of Independence. But I also wanted to walk in the footsteps of its more recent heroes – those who bravely helped the Allies in both world wars. I have written of its experience of WW2. Today I write of its history and Samos’ lesser known role in WW1.

I came to Samos in July, the Island basking in summer sunshine and the waters full of sailing boats and bathers. Arriving at the capital of Vathy is the best place to start your Samos experience. Along the harbour just outside the Town Hall can be found the Lion Statue, erected to commemorate the centenary of the Greek war of independence. Nearby is one of Samos’ impressive archaeological museums. And after a tour of the museum it is surely time for a refreshing stop at one of the many tavernas, to enjoy some of Samos’ muscat wine, famed since antiquity. The success of its winemakers draws on Samos’ fertile soil. It is no wonder that the classical poet Anacreon, who came to Samos from Asia Minor, praised Samos’ wine in poetry, once calling on all to bring on Homer’s lute, obey the laws of wine, to drink and dance!

Any visit to Samos must involve a journey across the Island to the port of Pythagorio, with its statue of the great mathematician Pythagoras who was born on the Island in 580BC, and the nearby archaeological sites of the Heraion and the Tunnel of Epalinos, together rightly listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Herodotus once wrote that the former contained “the largest of all temples we know of”. One cannot but be impressed by the great column and altar dedicated to the Goddess Hera, said to have been born nearby on the banks of the Imvrassos River. The Tunnel is one of the engineering achievements of ancient civilization, carved from the solid rock, creating an underground channel to provide fresh water to the then capital. South-west of Pythagorio is another reminder of Samos’ part in the Greek war of independence, the ruins of the Castle of Logothetis, the headquarters of the leader of the Samian rising of 1821 Lykourgos Logothetis and said to have been built on the site of Samos’ oldest acropolis. Standing near the Castle, outside the Church of the Transfiguration – erected to commemorate the Greek naval victory of Gerontas in 1824 – is Lykourgos’ statue.

Looking down on the Aegean from Samos’ forested mountains and cultivated valleys one is immediately struck by the importance of the sea to the Island. It would be its location in the Aegean that would see Samos’ population engaged in the First World War. Where Lemnos (along with Imbros and Tenedos) played key roles in the Gallipoli campaign, the people of Samos would take a major part on one of the lesser-known but important Allied campaigns of the war.

After the Gallipoli campaign, the Allies maintained naval and other forces in the Aegean to protect the supply lines to their troops on the Salonika Front and to ensure that Ottoman naval forces did not enter the Aegean. It was between March and October 1916 that the Allies decided to take their defence a step further and conduct a series of raids on the Asia Minor coast. The main aims of these raids was not only to harass Ottoman forces and destroy military infrastructure but also to round up livestock, denying it to the enemy who were seizing it from the local owners for transport to Germany then suffering from the Allied naval blockade.

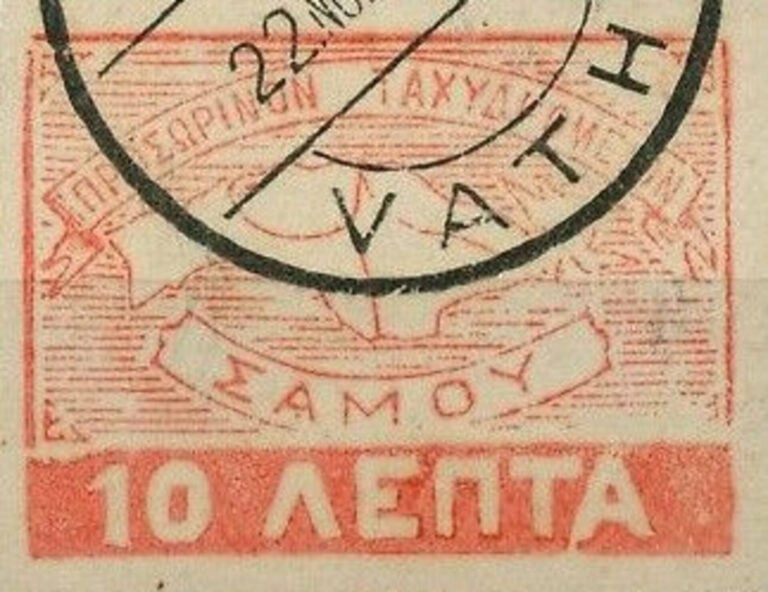

The raids would be led by British naval officers and comprise both armed and unarmed Greek volunteers. Following in the footsteps of Anacreon, some of these Hellenic volunteers came from Asia Minor; many others were recruited from the Aegean Islands, including Samos. It was estimated that Samos alone provided “some hundreds” of these volunteers, with much competition for the right to join up. The volunteers were engaged on a monthly contract, received training and arms, and were allowed to keep approximately 50 per cent of the animals seized, with additional payment for captured Ottoman soldiers and military equipment.

They were organized by village in squads of ten – dekanos – wearing distinctive head kerchiefs “of which they were very proud”, reported one of their commanders. They would sail as part of three detached squadrons consisting of both Royal Navy vessels and local Greek caique fishing boats. One of these vessels – the Monitor M33 – is preserved at the British Royal Navy’s Museum at Portsmouth, England. The raiders would sail from bases established across the Aegean Islands – at Lesvos, Agathonisi, Astypalaia and Leros – as well as from Long Island (modern day Uzunada, ancient Drymoussa) in the Gulf of Smyrna.

The raids began in March with the landing of 36 Greek volunteers and their Royal Navy officers just north of modern day Kusadasi. The raid was considered a great success, with nearly 700 animals seized. Ambushing local Ottoman forces, the Greek volunteers captured six and wounded several more. The whole landing was supported by shelling from the HMS Whitby Abbey. Commending the volunteers, their British Lieutenant Commander Drake wrote that “no better men could have been found than the irregulars, they acted with promptitude and pluck, obeying the orders given them.”

At the end of April, 150 Samian volunteers in 14 fishing boats joined HMS Aster and HMS Whitby Abbey in another raid near Kusadasi. Despite being subject to enemy air attacks and suffering 2 Samian volunteers killed, the raiders took off nearly 2,000 cattle. In May another raid saw over 230 livestock taken for no loss. In June, 25 Greek volunteers from Samos, Kos and Kalymnos raided Karada (modern day Bodrum) attacking an Ottoman patrol, killing 8 and capturing 7. This was followed by a large raid in July at the northern end of the Smyrna coastline, comprising a number of Royal Navy vessels and 18 local fishing boats carrying over 170 Greek volunteers. This force spread far inland, destroying communication and other military targets and herding over 3,100 livestock animals. The last major raid took place in September at Asin, where 130 volunteers supported by 2 destroyers and 3 trawlers took off 300 head of livestock. These were just some of many raids conducted across the Asia Minor coast throughout 1915, from Bodrum to Ayvalik.

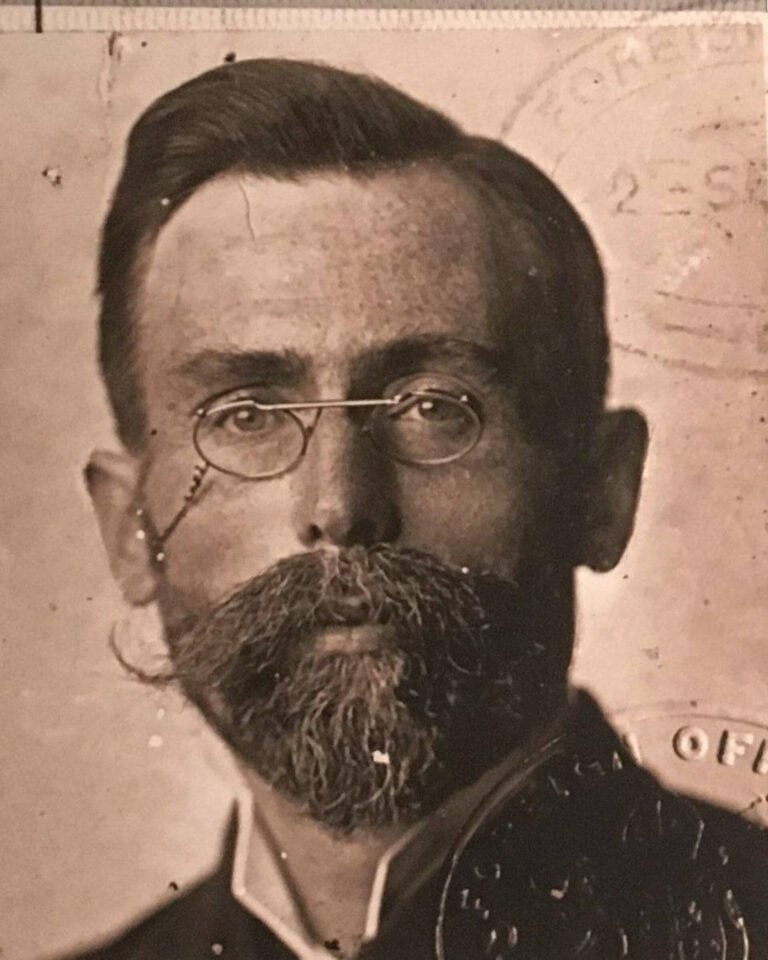

Some of the raids were led by British Royal Naval Reserve Officer John Myres, a pre-war Oxford Classics Professor who had travelled throughout Greece and Asia Minor before the war. His part in the raids would earn him the title of “the Blackbeard of the Aegean” and he would record his account of the raids in his memoir Praeterita.

One of the volunteer leaders was Asfalia from Samos –generally known as “Longshanks.” His leadership and military skills were such that he was recommended for permanent engagement with the Allied forces. Another was known as “Blue Eye” – probably the alias of one Aleko Anastasiades – a former regular soldier who loved to be part of the fighting. Surnames like Maillis, Argyris, Tseros, Kajahianos, Bambakas, Bourjoukas, Kontogeorgis, Konstantianos, Sophoulas, Stylianou, Leventis, Pagonis and Viananos can be found in the raiders’ archive. The raiders had their own chaplain, an unbeneficed priest, “a sort of Orthodox Friar Tuck”.

Myres wrote that the raids were preceded by the volunteers attending church, followed by hearty meals, of olives, bread, grapes, the occasional lamb, with coffee and tobacco! The raids saw some Asia Minor Greeks fearing reprisals being brought to safety. In September a farmer named Hadji Stephanos was brought off with his family, his furniture and stores due to these concerns. But the intimate connections between locals on both sides of the border would see Myres face the fury of one female Samian owner of a building on the Asia Minor coast destroyed as part of a raid! Samos was not only a source of volunteers, but its ports were regularly visited by the raiders, and its livestock traders feature as purchasers of the fruits of the raids.

While the raids were deemed a success, tying down some 6,000 Ottoman troops, international concerns at the use of irregular forces and Venizelos’ need to recruit locals for his anti-royalist force saw the raids end in October. For his service Myres would be promoted to Lieutenant Commander, awarded the Order of the British Empire, the Greek Order of George 1st and mentioned in dispatches.

As I sat on the balcony of my hotel, drinking Samian wine and eating fresh strawberries, I wondered if any of the locals wandering in the street below were descendants of these brave Samians. It would be great to find out if there are any local recollections of this aspect of Samos’ history. So here’s a toast of fine Samian wine to the Goddess Hera, Pythagoras the mathematician and the poet Ancareon, to Lykourgos Logothetis and liberators of 1821 – and to Asfalia and the Samian Raiders of 1916!.

Maybe the time has come for a commemorative plaque dedicated to Lieutenant Commander Myers – the Bluebeard of the Aegean – his brave Samian followers and their little known but essential part in the WW1 Allied campaign in the Aegean.

*Jim Claven is a trained historian, freelance writer, Secretary of the Lemnos Gallipoli Commemorative Committee and author of Lemnos & Gallipoli Revealed: A Pictorial History of the Anzacs in the Aegean, 1915-16. For more information see J.N.L. Myers’ Commander J.L. Myers RNVR – The Blackbeard of the Aegean, Richard Clogg’s “Academics at War” in the British School of Athens Studies (Vol 17:2009), Hadaway’s Pyramids and Fleshpots and Halpern’s The Royal Navy in the Mediterranean. He can be contacted at jimclaven@yahoo.com.au.