A few years ago a statue of a Greek Prime Minister went missing. Did this happen in Athens? Thessaloniki? No, it happened in East Brunswick.

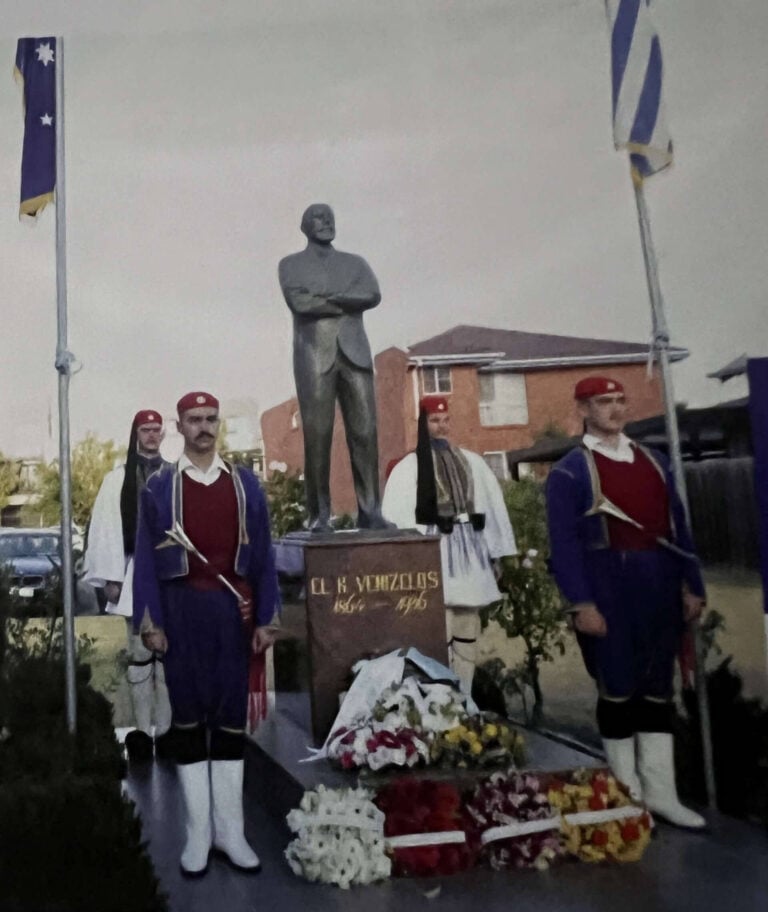

For decades, a statue of Eleftherios Venizelos stood prominently outside the Cretan Brotherhood Hall in East Brunswick. Over the years, the statue watched over hundreds of young Cretans attending their dance classes, and confused many passersby catching the tram to work.

However, the statue no longer watches over East Brunswick. Initially, it was moved into storage to make way for a property development, but it has since vanished into thin air, devastating the Cretan Community that commissioned it. Like many others, the Cretan Community was already struggling with the slow demise of its first generation members, but now it was also left mourning the loss of what should have been a permanent legacy.

The Cretan Community weren’t the only victims of such a heist though, in fact multiple statues around Brunswick were targeted around the same time, including installations of Father John Brosnan outside of the Brosnan Centre, and the locally lauded ‘Sparkly Bear’ at Barclay Square. The Cretan Community was likely just another victim of a professional crime syndicate, who potentially melted down the statue of Venizelos to profit from the value of its metal.

Just like the Golden Statue of Athena that graced the Parthenon, and the Colossus of Rhodes that towered over incoming boats, the statue of Venizelos is now just a memory, leaving an empty space on the Cretan Brotherhood property, and a pain that is carried by the Cretan community’s members. It was a pain that I had been carrying undisturbed for years, until a friend of mine shared a link that reopened that poorly healed wound.

What was shared with me was a series of Facebook posts, published by Greek-Australian author Dean Kalimniou, telling the fictional story of an effort to recover of the statue of Venizelos. Being so close to the actual incident left me squirming at the fictional account of my community, and unable to stomach even just the first post. I was too angered by the reality of the situation, that the missing statue was gone for good, and with it, also a part of the community’s identity.

However, the story did help me realise that the statue of Venizelos was significant to many beyond the Cretan Community. I began to reflect on the impact of public art and the contrasting works commissioned in Greece and Australia. The statue of Venizelos was in fact a bridge between these two art worlds, demonstrating a European tradition of historically inspired monuments, as well as representing a part of Australia’s more eclectic public art scene.

When I think about European public art, the images I conjure up tend to be works inspired by historical events or people. These include statues and fountains installed over the course of hundreds of years by wealthier classes of people, often to reinforce their own cultural dominance. In Greece this includes statues of priests, politicians and revolutionaries, so as a consequence, walking through a city can also feel like a journey through its history, showcasing its key figures and events. The statue of Venizelos was very much of this tradition, offering the local community a view into early 20th century Greece, and projecting the contribution of the local Cretan Community in the area.

In contrast, when I think about Australian public art, the images I conjure up tend to be more abstract. Think ‘Vault’ in Southbank, or ‘Three Businessmen’ on Bourke Street. There are of course many historical figures immortalised in our cities, however these are less prominent in Australia then in Europe. Rather than offering an external story for viewers to engage with, abstract art can inspire a more introspective line of questioning. ‘How does this make me feel?’ rather than ‘Who is that?’. In this context, the statue of Venizelos stands out as something that was quite different to what you’d typically expect in Brunswick – that is until you also consider the diversity of Australia’s public art ecosystem.

Unlike cities like Paris or Athens, which are dominated by more homogenous aesthetics and where new art is held up against a more defined standard, Australian cities offer a relatively blank canvas that grows with its sprawling suburbs. Partly because of this, Australia’s public art can also be very eclectic, but this is also a reflection of Australia’s diverse cultural communities. In this way the statue of Venizelos was very Australian, it was bold, seemed initially out of place, but came to be a loved part of the neighborhood – just as the Greek diaspora found its place in Australia’s multicultural community.

However, this same multicultural environment can often give rise to works that are deliberately not reflective of anyone. In an effort to avoid offending some or excluding others, councils often err towards the safety of abstract or broad pieces. In this way, the statue of Venizelos stood out as a bold form of community self-expression that almost certainly would never had existed were it not for community self-funding.

Ethnic communities often find it extremely challenging to receive council and government commitments for such monuments, as they can trigger political controversy due to their subject matter or community controversy due to their permanence. Although dissenting members of the community can stomach council funded murals (which can be graffitied), or festivals (operating on a year by year basis), statues are often subject to increased scrutiny in part due to their expense and prominence. As such, statues are often subject to local opposition for many reasons, even sometimes from communities that are seen as advocates for diversity.

This was seen when a statue of King Leonidas was the subject of great opposition ahead of its installation in Brunswick. Some traders came out in public decrying the imminent installation (supposedly on artistic grounds) which was set to acknowledge the council’s large Laconian population as well as its sister city relationship with Sparta. Thankfully for the Greek community though, the statue was eventually installed and today can be found welcoming passersby on their way to the nearby shops or when coming to enjoy one of the famous local live Jazz nights.

The King Leonidas case study underlines the importance of independent community self-expression as well as the challenges of getting into bed with councils or governments. The statue of Venizelos was rare in that it was community funded and as a result, represented a bold form of community-self expression. Encouragingly though, the statue of Venizelos would still eventually become an accepted and valued part of the broader neighbourhood, just as was the case for the statue of King Leonidas in Brunswick, the statue of Saint Dimitrios on Lonsdale Street, and the Lemnos Gallipoli Monument in Albert Park.

What’s fascinating about the integration of monuments within neighbourhoods is that the integration is characterized by unique relationships that vary from person to person. In the case of the statue of Venizelos, some people loved it for its artistry, for others it was a favourite landmark on PokemonGo, and for many people I suspect it was simply a curiosity that they passed on their daily walk to the nearby tram stop.

As a member of the Cretan Brotherhood, I was told how the statue of Venizelos provided a focus for my Grandparent’s community work, and oversaw my father take my mother to her first Cretan functions. The statue watched me grow up playing soccer with my brother after dance practices, and provided a quiet space for me to talk with my mates during Youth Tavern Nights. But for me the statue provided more than just a physical presence, it also inspired curiosity. The statue of Venizelos caused me to question why politicians inspire monuments, to learn more about modern Greek history, and to accept that Greeks do deserve to be commemorated in Australia.

The statue of Venizlos helped me explore my cultural identity and it was my hope that in spite of deteriorating Greek language usage and diminishing community institutions, that the statue of Venizelos would still be there to inspire my children with the same curiosities. Who is this guy? Who put him here? By inspiring these kinds questions, the statue of Venizelos would have done its job, by guiding people towards answers that reveal the history of the local area and insights into their own identities.

The loss of the statue now means that these questions will not be asked by future generations in the same way, but rather than silence, I hope that the void is replaced with a warning for us as we navigate our changing community. We are already struggling with a fading first generation of migrants but we must also recognise that even their physical legacies aren’t permanent without responsible custodianship. We cannot take any aspects of our community infrastructure or legacy for granted.

That takes us back to the current reality. The statue of Venizelos is gone, and unfortunately Kalimniou’s fiction won’t bring him back. It’s my sincerest hope though, that we have learnt our lesson from this tragedy and that in response to the loss of one statue, many more will one day take its place.

When I contacted the Cretan Brotherhood on the issue they echoed this sentiment. President Milton Stamatakos provided the following statement:

“The Cretan Brotherhood of Melbourne and Victoria, together with its committee, remains deeply committed to honouring the legacy of Eleftherios Venizelos. His statue stood proudly outside our club for decades as a symbol of our heritage, our community’s history, and our connection to both Crete and Australia. We are determined to see the Venizelos statue restored to its rightful place, so it can once again stand prominently at the front of our Brotherhood and continue to inspire future generations.”