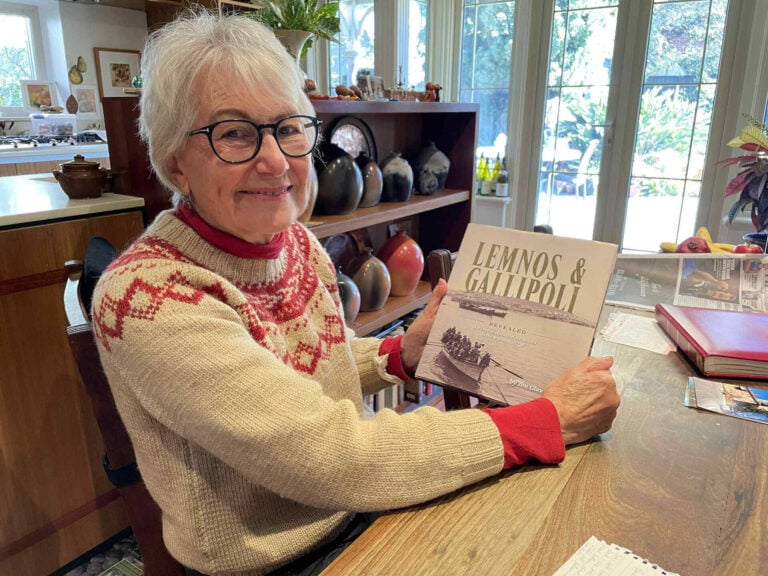

The sun streamed through French windows as Alexandra Lovell (née Alexandridis) outlined her story of migration and survival across generations.

Her family history stretches from the Greek communities of Pontus to Russia, Georgia and Ukraine, and from Thessaloniki to Australia. It spans the days of the Ottoman and Tsarist Russian Empires, the Asia Minor Catastrophe and refugee resettlement in northern Greece, and follows the broader social upheavals of modern Greek history.

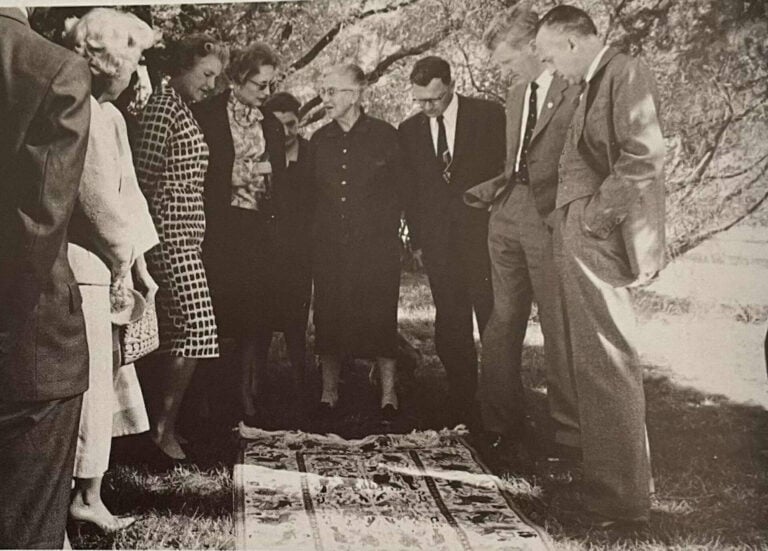

What had drawn the three of us together was the work of Australian refugee workers Joice and Sydney Loch, who lived and worked in northern Greece in the years following the Asia Minor Catastrophe. They were based at the Tower of Ouranoupoli, assisting in refugee resettlement there and at the American Farm School, helping Greeks displaced from the former Ottoman Empire to rebuild their lives.

Alexandra was excited to learn that Melbourne artist George Petrou and academic Dr Harry Ballis had recently visited both the School and the Tower to commemorate the work of the Lochs, with gifts of George’s paintings. The events were attended by the Australian Ambassador to Greece, Alison Duncan. A member of the Greek Community of Melbourne and an avid reader of Neos Kosmos, Alexandra had read about this in my earlier article.

Dr Ballis has since embarked on his own journey of discovery, researching the life and work of the Lochs with the aim of producing a new, groundbreaking biography. His work has taken him to archives in Australia, Greece, and the United Kingdom, where he has uncovered a vast collection of material previously unexamined. This research will allow for the first comprehensive and thoroughly documented biography of these important Australians.

My own interest in the Lochs began years ago when I visited the Tower and its museum, which revealed tantalising glimpses of their story. At the time, I had been researching the life and refugee work of Ballarat’s Major George Devine Treloar in northern Greece—a journey that took me to Thrace’s Thrylorio and Komotini, and ultimately led to the creation of the George Treloar Memorial in Ballarat.

Imagine our excitement when Alexandra laid out her personal archive before us: original photographs, rare publications and reports, letters, and official documents, all offering fresh insights into the Lochs’ story and more. Around her large dining table, she began to weave her family history and its connection to Joice and Sydney.

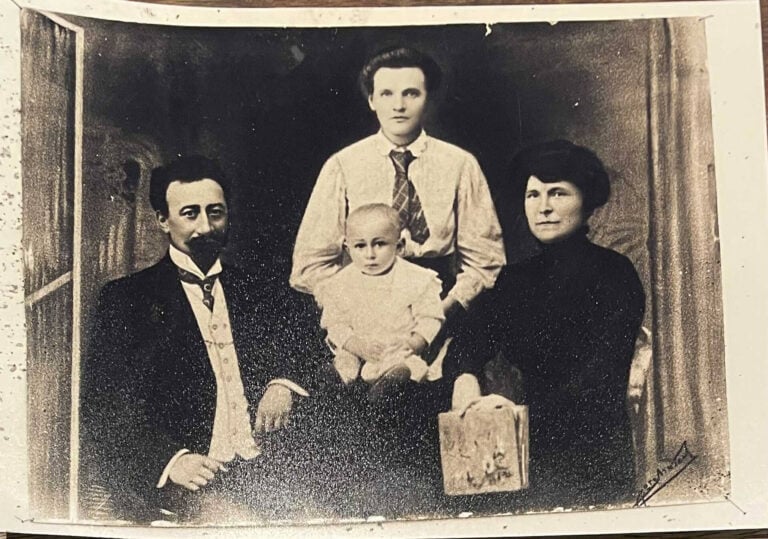

Her grandparents had been deeply affected by the turmoil that followed the First World War. Her paternal grandfather, Elias Alexandridis, was a Pontian Greek who had moved to Batumi in Tsarist Russia at the turn of the century. A photograph shows him as a successful trader, immaculately dressed with his wife, son, and governess. His wife, Alexandra (née Shlusarenko), was of Ukrainian or Belarusian birth, and their son Panayiotis—Alexandra’s father—was born in 1908. Their stately two-storey home was abandoned when the Russian Revolution and Civil War forced them, like hundreds of thousands of others, to flee across the Black Sea. Known collectively as “White Russians,” many sought refuge in Allied-occupied Constantinople before moving on.

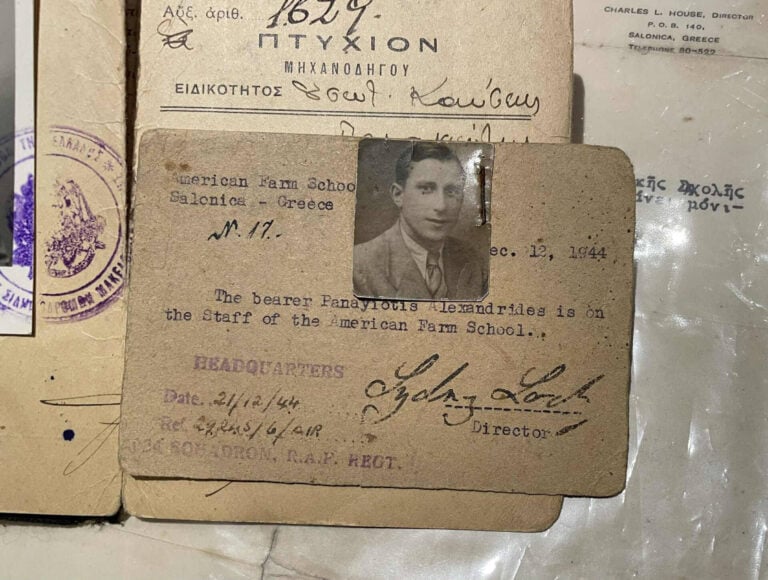

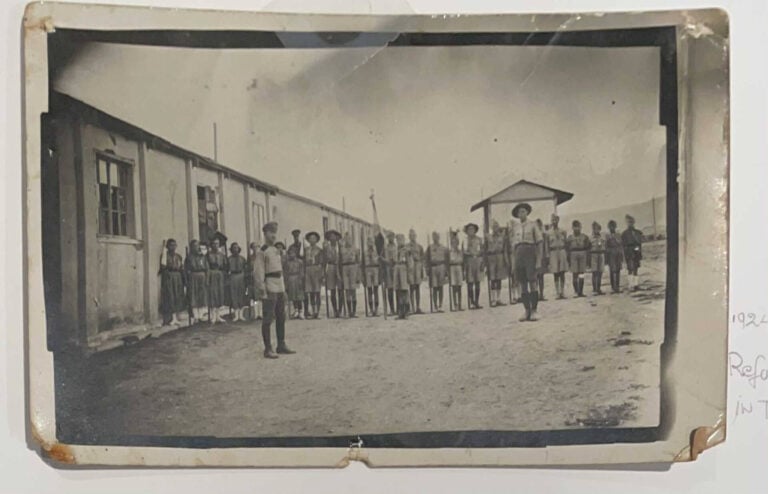

By 1921 the family had reached Thessaloniki. Alexandra’s photos include a number of these White Russian refugee camps in Greece, showing the camps looking well-kept with many of the refugees in Tsarist uniforms. The family arrived in Greece in 1921. However the family’s arrival in Greece was bitter sweet. Alexandra’s father and his mother settled at the American Farm School near Thessaloniki in 1928, where her father was engaged as a mechanic and driver and his mother worked as a cook in the kitchen. The family had comfortable lodgings at the School. But this good fortune was to be tempered by the earlier disappearance of her grandfather on an earlier trip to Athens in 1925. He was never to be heard of again.

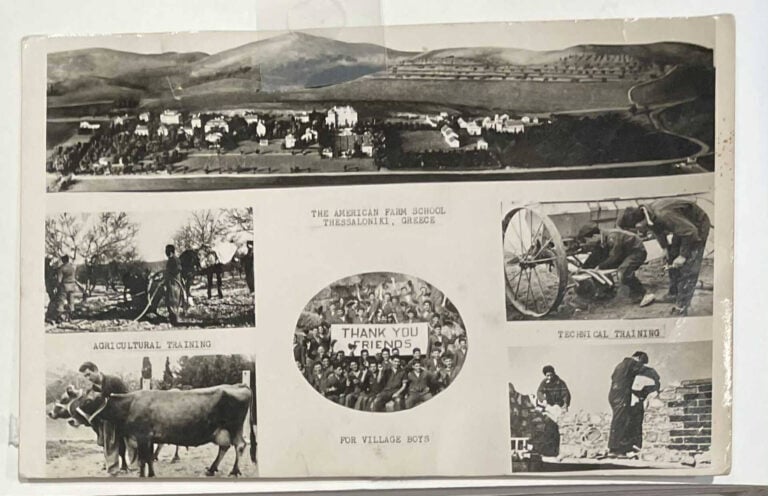

The American Farm School had been established in the early 20th century on a 50 acre property granted on a lease authorized by the Ottoman authorities who governed the area at the time. The School was started by the practical idealist, Dr John Henry House with funding from friends in America. The School was inspired by some Quaker teachings, particularly the idea of learning by doing. The aim of the School was to provide training in agricultural techniques to the people of the southern Balkans and thereby help their economic and social development.

It was there that Alexandra’s father met and married her mother, Elli Limperi, in 1946. Elli’s family were Smyrna refugees who fled the burning city in 1922. Alexandra recalls her maternal grandfather, Yiorgos Limperi, being saved from the harbour by his wife Evangelia, who pushed him towards safety despite his inability to swim. Settling in Thessaloniki, they raised six daughters, Elli among them.

Alexandra was born at the Farm School and lived there with her family and grandmother. It was during this time that she first encountered Joice and Sydney Loch. The couple had arrived in the 1930s to continue their humanitarian work under the Society of Friends (Quakers). Sydney was appointed Director of Academic Programs, teaching mathematics and sport, while Alexandra’s father became his driver, taking him across northern Greece. On one trip, they delivered clothing to refugee families in Aridaia, where Harry’s grandmother and uncle had settled.

Alexandra’s recollections, supported by photographs and documents, give unique insights into the Lochs’ daily life and character. She even showed us a School record bearing Sydney Loch’s signature. Her archive also includes photos of Farm School life—staff groups, family homes, children’s parties—and official documents ranging from driving licenses to wartime papers stamped with the Nazi swastika. These reflect the precariousness of her father’s position as a stateless refugee.

Although Pontian by heritage and Orthodox by faith, the Greek authorities long refused to grant him citizenship, seeing only his Russian background. With the advent of the Cold War and the Greek Civil War, suspicion intensified. The Farm School encouraged the family to migrate to Australia, and Joice Loch herself reassured them.

In 1953, despite her grandmother remaining behind, the family set out for a new life. Alexandra remembers the tense moment when her father was interrogated by Greek officials at Piraeus before being allowed to board the Ana Salen. The family’s Australian story began at Bonegilla camp, then in Tasmania where her father worked on the hydro-electric scheme. Despite hardships, they soon purchased a home in Albert Park in 1956, gaining the stability they had long sought. Alexandra describes her mother as the resilient heart of the family, always remaining positive.

She herself became one of the first post-war Greek women to train as a secondary school arts and crafts teacher at Melbourne Teachers College—a story for another day.

As we shared Alexandra’s delicious lunch—pumpkin frittata with rocket and pear salad, followed by Greek orange and almond cake—we reflected on migration: its losses, gains, nostalgia, and new beginnings. It was a conversation to be continued.

*Scots-born Jim Claven OAM is a trained historian, freelance writer and published author. Dr Harry Ballis, of northern Greek heritage and a former Monash University academic, is working on a new biography of Joice and Sydney Loch. Both Harry and Jim are deeply grateful to Alexandra for sharing her story. Jim can be contacted via email at jimclaven@yahoo.com.au