Seán Damer’s Wild Mountains, Wild People belongs to a venerable tradition of war novels set in Crete during the Second World War. Its landscapes, haunted by German paratroopers, British commandos, and andartes, are familiar to readers of W Stanley Moss’ Ill Met by Moonlight, George Psychoundakis’ The Cretan Runner, James Aldridge’s The Sea Eagle, and Patrick Leigh Fermor’s Abducting a General. Damer however does not rehearse the tale of aristocratic adventurers operating behind enemy lines. His novel, presented in epistolary form, moves between Scotland in the present and Crete during the occupation, tracing the fraught legacy of wartime choices through the story of Gallagher, a Glasgow commando who vanishes during the war and is later revealed to have lived for decades in Crete with a Cretan wife. The discovery of his journals forces his grandson Andy, a classics professor steeped in Minoan studies yet emotionally adrift, to confront the collapse of his marriage and the uncomfortable inheritance of divided loyalties. Damer situates this intimate narrative within the ruins of public history, binding together the shards of family, politics, and memory into a single mosaic.

Within the canon of Cretan war literature, Damer’s novel both acknowledges and departs from its predecessors. Moss’ Ill Met by Moonlight celebrated the kidnapping of General Kreipe, casting the Cretan resistance as a picturesque backdrop to British chivalric heroism. Psychoundakis’ The Cretan Runner, though rooted in lived experience, reached readers through the mediation of British publication, while Aldridge’s The Sea Eagle privileged the ingenuity of special operations. Leigh Fermor’s later memoir, Abducting a General, returned to the episode of the Kreipe kidnapping from the vantage point of reflective recollection, shaped by his own cultivated prose and self-fashioning. Damer’s narrative alters the vantage point altogether. The epistolary form allows the reader to inhabit Gallagher’s words. His political sympathies with ELAS, his accidental killing of an SOE officer, and his decision to vanish into the Cretan underground are revealed through testimony. This is the story of a working-class Glaswegian whose socialist background disposes him to see the partisans as comrades. His vision contrasts with the upper-class officers of the Special Operations Executive who refuse to arm ELAS, branding it communist. In this way Damer challenges the orientalist tendency of earlier works, which often romanticised the Cretans as noble primitives whose bravery derived from ancient vendettas rather than from ideological conviction. Gallagher, though foreign, attempts solidarity across class lines, reading the resistance as a continuation of proletarian struggle.

The question arises whether Damer’s Cretans exist as independent characters or merely as scenery for the Gallagher family drama. Here the evidence is mixed. Figures such as Kostas Sfakianakis, the partisan guide killed during an airdrop, or Yorgos, the teenage runner who risks everything for the cause, are vividly sketched in the early chapters. Their courage and resilience are palpable and their sacrifices frame Gallagher’s own decisions. Maria Sfakianakis, the widow with whom Andy finds companionship in the present, provides continuity across generations. Nonetheless, the Cretans often appear through the filter of the British gaze. Kostas is noble in death, Yorgos legendary in endurance, Maria a vehicle for Andy’s redemption. The novel does not grant them sustained interiority. Their voices emerge through the mediated words of Gallagher’s journals or Andy’s encounters. War novels often use the local population as backdrop, against which the foreign protagonist negotiates his own crises of loyalty and survival. Damer’s work, for all its sympathy, does not entirely escape this gravitational pull. The Cretans are present, brave, and indispensable, yet their complexity is necessarily subordinated to the Gallagher family’s narrative arc.

What distinguishes Wild Mountains, Wild People most strongly from the earlier tradition is its acute attention to class. Gallagher is not an Old Etonian adventurer. He is the son of Glasgow socialists, a joiner by trade, formed by the culture of Red Clydeside. His sympathy for ELAS emerges from political kinship. The conflict between Gallagher and his English superiors dramatises the gulf between working class internationalism and the suspicions of an imperial military hierarchy. The accidental killing of an officer, which seals Gallagher’s fate, symbolises the irreconcilability of fraternal solidarity with partisans and the rigid demands of the British establishment. His subsequent withdrawal into the Cretan underground is transfigured into an act of ideological constancy, a refusal to betray conviction. In that gesture he renounces the institutions of the West which denounce comradeship as subversion, and seeks instead in the symbolic “East” a realm where political and moral commitments can be authentically enacted.

This theme of turning away from the West towards the East has a long literary lineage. In T.E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, the desert becomes a place where Western identity dissolves and an alternative self is discovered. In E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India, the encounter with the subcontinent unsettles imperial categories and forces a confrontation with other modes of being. In Nikos Kazantzakis’ Freedom or Death, Crete itself is the crucible in which European values are tested and transformed. Gallagher’s embrace of the Cretan underground participates in this trope. He refuses to act as the agent of empire and instead finds comradeship among mountain fighters whose struggles mirror those of his own class at home. The trope risks exoticising the East as a site of authenticity, yet in Gallagher’s case it is framed through class rather than romance, which tempers the danger of orientalism.

Andy, the protagonist’s grandson, embodies a later stage of class displacement. Though descended from working class stock, he has become an academic specialist in Minoan script, comfortable within the university yet emotionally adrift. His inability to sustain his marriage mirrors his difficulty in interpreting his grandfather’s legacy. Redemption comes only through his confrontation with the Cretan mountains and with Maria, suggesting that class identity, when transfigured into abstraction, requires re-grounding in lived struggle. The novel therefore stages a double movement. Gallagher embraces the East as the arena where his class convictions achieve embodiment. Andy, estranged from both class roots and family ties, rediscovers authenticity only in Crete, through a belated encounter with the land where his grandfather chose to remain.

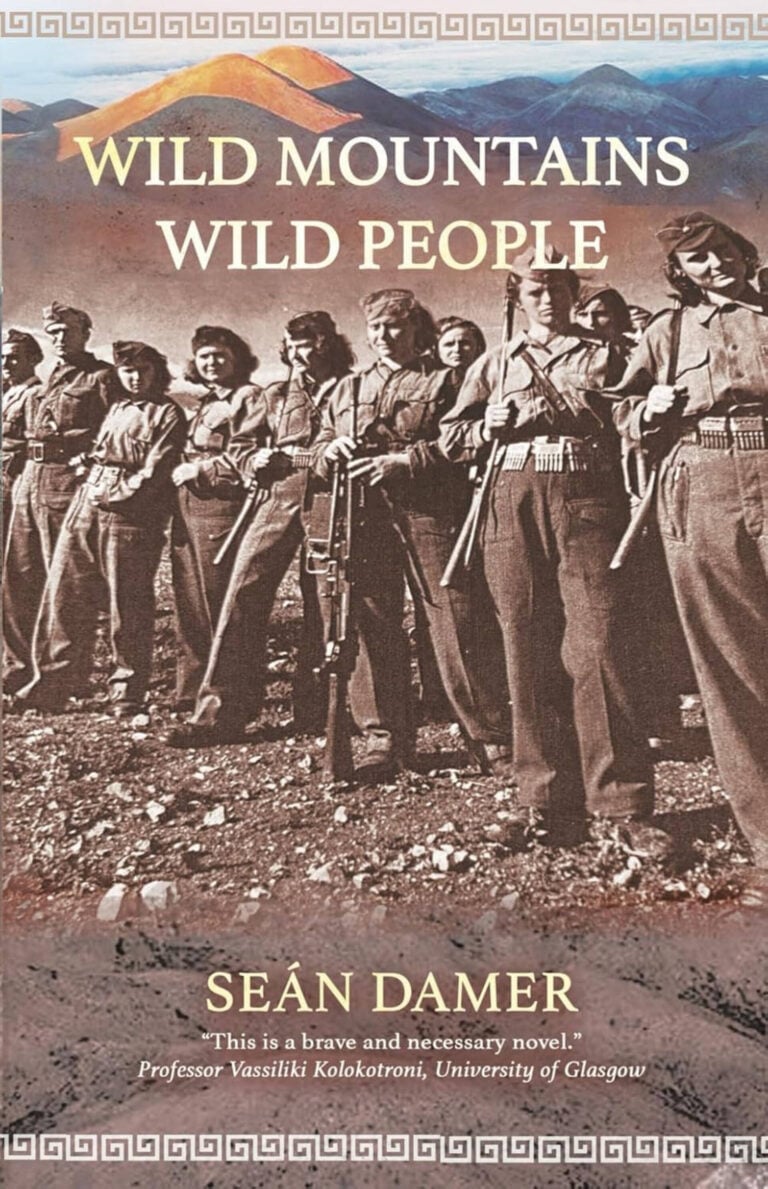

The novel’s title, derived from the proverb that wild mountains breed wild people, points to the delicate balance it maintains between solidarity and orientalism. There is always the risk that Crete may be cast as a theatre of vendetta, passion, and fatalism, yet Damer’s narrative largely avoids such reduction. Gallagher sees the Cretans as comrades bound by shared struggle rather than as enigmas. The novel also highlights the political fractures within the resistance and situates them within global ideological conflict rather than attributing them to timeless tribalism. Images of the sublime mountains and of Maria as a striking Mediterranean figure recall familiar literary conventions, yet here they function less as distortions than as devices to heighten atmosphere, leaving intact the authenticity of the work’s sympathies.

A distinctive feature of Wild Mountains, Wild People is its reliance on epistolary structure. Gallagher’s letters to his fiancée Maeve, his journals from the war, and the contemporary correspondence that summons Andy to Crete create a fragmented narrative. War literature often emphasises the incompleteness of testimony. As Paul Fussell has argued, the form of war writing is inseparable from its fractured content. Damer embraces this incompleteness, and the reader must reconstruct events from scattered papers. The censored blandness of Gallagher’s official letters contrasts with the intensity of his hidden journals. This juxtaposition exposes the distance between public discourse and lived reality. The device also underscores the fracture between generations: Andy reads his grandfather’s words as a stranger, alienated from their immediacy, much as he is estranged from his own family.

The epistolary form conveys both authenticity and disorientation. Its danger lies in loss of narrative momentum. At times one longs for immersion in Gallagher’s experiences rather than piecemeal reconstruction. Yet the very incompleteness is the point. As Samuel Hynes observed, war leaves only fragments, and descendants must interpret them as best they can. The device therefore functions as a thematic necessity, a formal acknowledgement of the limits of testimony.

Damer’s narrative closes without the reassurance of reconciliation. Gallagher’s decision to remain in Crete emerges as the creation of a new belonging that unsettles conventional lines between victor and vanquished, native and foreigner. Andy’s belated attempt to interpret that choice reveals how memory resists domestication and remains jagged, like the mountains themselves. In this sense the novel enlarges the canon of Cretan war literature by reminding us that occupation was never a mere episode in a distant campaign but a crucible of identities contested across generations.

The wild mountains do not simply house wild people. They guard the restless echoes of history, which, as Edward Said might remind us, are never innocent of power, and which demand to be heard long after the last shot has been fired.