“The outpouring of love and respect for my father has been overwhelming and humbling. There were 270 people at his funeral, people staying outside. He would have been deeply moved, because he often wondered if people understood what he did”.

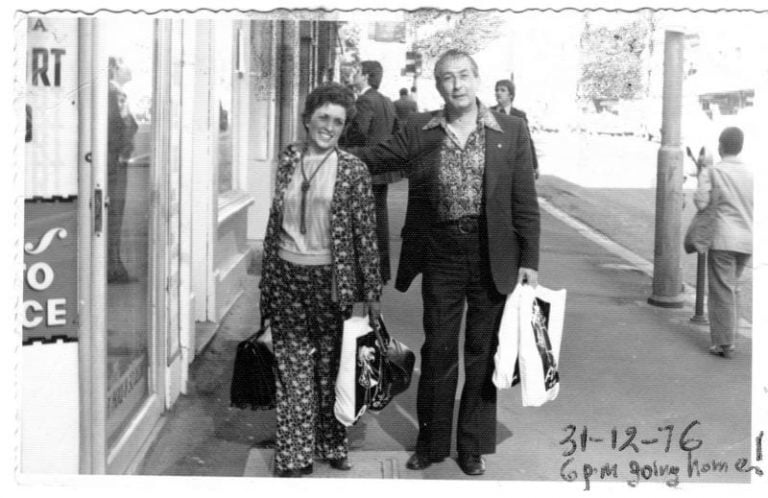

Paul Kouris is obviously moved himself, as he talks about the way the Greek community bid farewell to his father, the late Alfred Kouris. Ever since his passing, tributes to the man and his legacy abound, giving justice to the perception of Kouris as a beacon among the Greek Australians. A lot has been written. About his business success, with the Alfredo’s Men and Ladies wear”, about his ventures in politics, about his time as a publisher of a newspaper “Neos Pyrsos” (from 1985 to 1993), as a prominent member of the Greek Orthodox Community of Melbourne, a founding member of HACCI and the longtime President of the Greek Orthodox Community of Mentone & District. Looking to highlight different aspects of his personality, we reached out for his son, an accomplished barrister and successful inventor. He was happy to share his memories that paint a portrait of Alfred Kouris. This is his account.

He came to Australia, because it was very hard in Greece economically as well as politically, particularly for people who had been at the resistance. My father was not a communist, he was a republican, but that nice distinction was never made by the people who were trying to regain political control of Greece, like the monarchs who return after having spent the war in safety. My great-grandfather was a chief justice and he told my dad: “not even I can protect you; the whole world has gone crazy out here. Take your young wife and go as far South as you can”. So he went with my mother to the Australian Embassy in Athens, to ask for a visa. He’s well dressed, he speaks english, he’s well-educated, he comes from a good family, and he goes to this Australian bureaucrat, who he says: “show me your hands”. My father says: “why?” “Show me your hands; I want to see your hands”. So, he does and the officer goes: “These are the hands of the literati. You’re too well educated, you’re not the sort of person we want in Australia. We want peasants, people to dig the roads and plow the fields. I won’t approve your application”. So my dad goes back to his grand-father who says: “You’re going to work in your uncle’s farm for three months and go back and show him your hands”. And he did that and went back, only this time, both he and my mother were dressed peasants – and they took an interpreter with them. As they walked back in, my father’s heart sank, because it was the same man at the desk. Without even looking at my father, he turned to the interpreter and said: “tell him he’s exactly the kind of person we’re looking for in Australia” and gave him an assisted passage.

My father had studied politics and law at the university and he would have wanted to become a lawyer, when came to Australia but his qualifications were not recognised. Back then, if you didn’t have a degree from a British university, it didn’t matter. You might have been a professor in Greece, but you worked in the fields here. Your qualifications were not recognized. So he’s looking for a job in the paper and he saw that the famous “Pelaco” factory (in Richmond) was looking for workers. He went and asked: “what are you looking for?” “A cutter”. “I’m a cutter. I’ll start in a week”. He took that week to find out how to use the equipment. He thought to himself: “how hard can it be?”. That is how he went to work for them and how he found himself in the clothing business. Because he saw a need. Necessity is the mother of invention.

He would associate himself with busy people; that’s how he got things done. He had this idea: “if you want something done, give it to someone busy to do it. Because the lazy will not do it; you’re not going to get a lazy person disciplined by giving him something to do”. He was always suspicious of people who had too much time.

He urged me to go to law school and I was complaining because it was hard and I was telling him: “you’re telling me to be a lawyer, you have no idea what it’s like. It’s very hard”. And he said: “You’re telling me I couldn’t do it? If I can do it, so can you. I’ll enroll at RMIT in contract law and civil law. If I can do it, you’ll stay at university”. And it’s exactly what he did.

He sent my sister to a private school and me at Beaumaris school, which, at the time when I did my HEC, had a 45% pass rate, one of the lowest in the country. I asked him why he did that and he said: “Because your sister has to learn to become a lady. You have to learn to survive. If you can survive at Beaumaris high school, you can survive anywhere”. I said: “What happens if I fail?” “Then you’ll always come to work in the business” I did well and I went to law school. And he said: “You can do it the way I did it: work at the business during the day and study at night”. I didn’t want to do it, I wanted to be a full-time student. And he said: “you want to be a full-time bludger. Who’s going to pay for that?” The next year, Whitlam was elected and not only did he make everything free, he gave allowance for students, so they could study. And my father couldn’t believe this. He knew him and he told us that he rang him up and said: “how could he do that? You’re ruining my family!”

He was always involved in politics. In his book there is a photo of Malcolm Fraser doing the Zorba, between me and my mother, we were trying to teach him to dance hasaposerviko. He was trying to get the Greek community involved in politics, regardless of which side. He wasn’t saying that we should all be Liberal, we should all be Greeks. He said that we should all be involved. We should all be first class citizens and not just be parasites, getting the benefits without the burden.

He had always considered himself to be a journalist, an observer of society and commentator. A person who had something to contribute to the way society operated. After his career in retail and clothing, he went to Greece for a while, where he started a big furniture business in Kifissia. When the drachma was devalued by 30%, it devastated the business. So, he came back to Australia. I told him: “What are you going to do now?” And he said: “I’m going to start a newspaper”. “Just like that?” “Yes, why not? How hard can it be? I have friends. I know publishers. I can do this!” So, he started “Neos Pyrsos”. He felt that the community needed another newspaper as a counterpoint for Neos Kosmos. He enjoyed being another voice; a serious, educated, researched voice about community affairs, about the church, about the politics, the political situation in Australia. In his newspaper, he’d publish letters that were critical of him, he’d reply to them, we welcomed open discussion.

He was tired of seeing people come to shop with a sandwich in their mouths. People who were working, if they couldn’t shop during lunch time, by the time they finished work, all the shops would be closed. And on Saturday morning, they’d shop for their food. They do their grocery shopping from 9 till 12 and if they wanted to buy clothes, they’d do it from 12 to 1.

My father thought that this is ridiculous. he said it was uncivilized. The country was designed for the aristocracy. Only people that were rich could shop, those who were not working. This has to change. He was tired of seeing people come to shop with a sandwich in their mouth. So he started a campaign for the shops to stay open till late: “Make Melbourne Brighter”. He didn’t approve of the 24/7 trading that’s happening today, because this is an exaggeration. But he believed that shopping should be a celebration. People would come with their family and have a night out; it would liven up the city, make it an international city. That was a philosophy. And then he did another campaign for the liquor licence laws to change, to enable alfresco dining. When he started that, the chamber of commerce said that Australians would never be seen eating outside. But this is what resulted to him getting an OAM for his services to the community.

He believed that the well-educated in a society have an obligation, a duty, to help that society progress. There is no point in having a good education, if you’re not helping the society you’re living in progress. Because without progress, a society dies. And progress comes from the educated. He would say: “When I came to Australia in 1955, about 15% of Australians had a tertiary education. Among the Greeks who came to Australia, about 1% had tertiary education and most of them had barely finished primary school. The Australians brought people here who would have difficulty living in a big city in their own country. They would probably be living in their villages. If they went to Athens, they’d be struggling to settle into Athens. And the government brought them to Melbourne! To a strange culture, to a different language, with Anglo-Saxon emphasis; of course they would have difficulty learning to adapt in this new country”. It was hard and it was even harder because most of them were not educated in their own language. So, he wanted to introduce means by which the Greeks could integrate into the society. And he thought the first way to do it would be to provide a cultural platform.

That’s why, he started the Athenian Society, a group of people who were interested in literature, in poetry, in theatre. I remember going to many plays that he had put up and written himself. One of the plays was “Ο μετανάστης”, it was all about the difficulties of a migrant coming to Australia and dealing with the migrant experience and the anglo-saxon culture.They were always very popular.

One of the most significant things he did was the Academy. Growing up in the ’60s, we were always in fights because we were ‘wogs’. We wanted to become more Australians to stop the teasing. Our parents were worried that this would result to their kids becoming Australian at the cost of their Greek culture. One of the great fears that the Greeks had, was that they’d have to lose their children to the Australian Anglo-Saxon culture. So he established the Hellenic Academy of Modern Greek in Swanston Street to enable the children, as they go into their teens, to get a better knowledge of Greece and their culture. In the process of the children getting educated in Greek, the parents got better educated in Greek.

If the Greek Community had a ‘hall of fame’, to honour the legends, they should put my father among them; he should be honoured and remembered.He would have liked to have seen some tribute and recognition for all those community leaders who sacrificed so much and put time and effort to help the community progress. That would be nice.