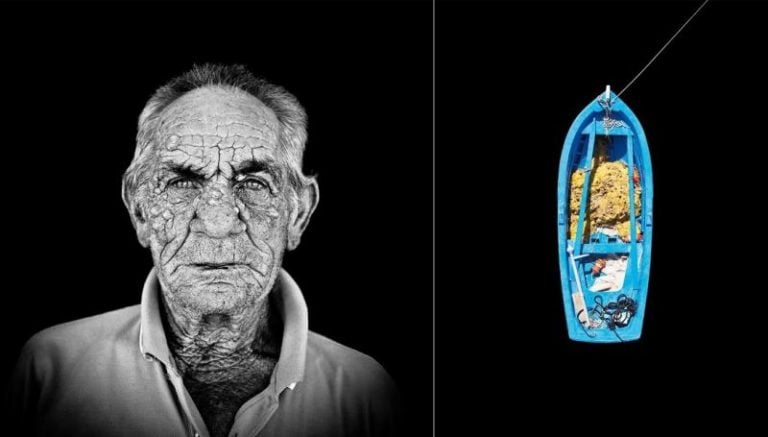

Since 2010, Vienna-based photographer Christian Stemper has documented a total of 99 boats and 31 fishermen on film, depicting the unsure future of the last ‘Wolves of the Sea’ in Paros island, Greece. “I was always fascinated by the old, Greek, traditional wooden fishing boats and wanted to photograph them from a different angle of view,” he says.

“As side shots I took some portraits of the associated fisherman. In 2013 I went to Paros again and realised that half of the boats that I had already photographed in 2010 did not exist anymore – destroyed, abandoned or sold to tourists. And the ones left will soon be gone – not only on Paros, but on all the Greek islands. No one of the young generation will become a fisherman anymore. The traditional fishing craft is dying, and therefore a millennia-old tradition.”

That was the moment of realisation that led Stemper to make a photobook. In October 2014 he travelled to Paros with a camera crew. They captured the work and life of the fishermen and the only remaining boat builder on the island.

“The photobook is the essence of thousands of photos I took, hours of interviews, and spending time with the old fishermen on Paros, listening to their stories, that hopefully will not be lost,” he reflects.

“I hope that LUPIMARIS will create a lasting memory of the last wolves of the sea and their boats.”

Stemper’s book is also a muchneeded historical account. On one hand, it is presented as a journalistic illuminated history of the individual, authentic characters. On the other, as an aesthetic image, the handmade fishing boats, which are represented in their uniqueness and variety of details.

Thanasis Tantanis, for example, a 75 year-old fisherman from Nàoussa, at the north of Paros, says: “I learned from my grandfather and my father. This knowledge will be lost as there is no one to follow the tradition. When we’re gone, it’s over.”

Many children born on the island left for the mainland to pursue further education.

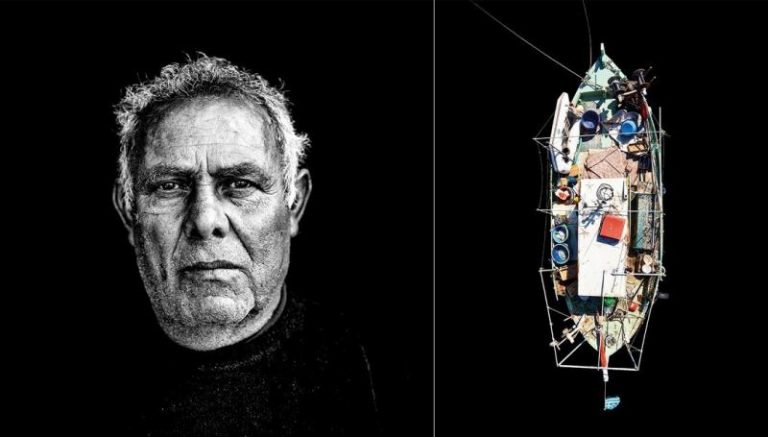

“At the age of 18, I became a sailor and travelled the world as a radio operator,” adds Petros Delentas, born in 1942.

“Not because of romantic reasons, but at that time there was nothing to do here,” he explains. “My boat saved me. It was my anchor that brought me back

to Paros and with which I was able to build my life. So that I could escape from a life as a sailor. This boat is my love.”

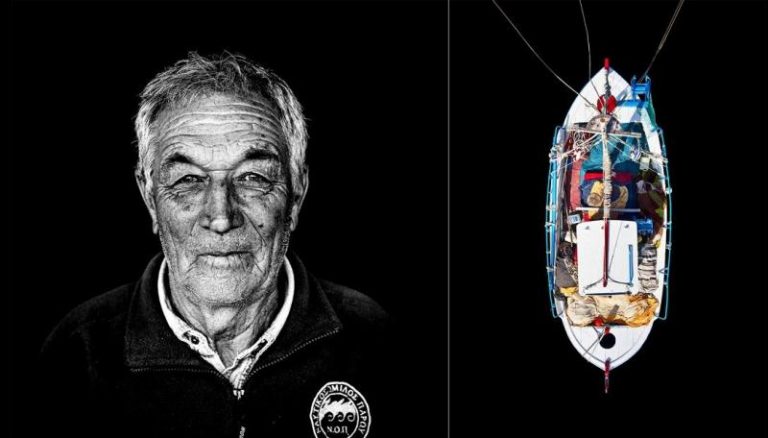

On the same boat, Vaggelis Parousis, another fisherman born in 1945, says that “if I do not see any sea, I do not live. If I had to stay in Athens, I would not even survive a whole twenty-four hours. I would go crazy.”

Seventy-two-year-old Filippas Tsantanis’ grandfather was a fisherman, and his grandson always looked up to him.

“They called him the Professor. I gothis nickname,” Filipas says, explaining that in his family there have been many fishermen and sailors.

“The individual branches of the family were distinguished by nicknames which are so old that no one knows when they originated. My grandfather often slept on his boat as he was always out there for days.”

Nikitas Malamatenios in Naoussa, owner of the boat Panagia, acknowledges that the future is not bright for their way of life.

“The work is difficult and the income less than before. There’s no attraction for a new generation.

“I have always been a fisherman − not out of necessity, but out of choice,” he emphasises.

Everyday life at sea, whether it be out of necessity or the toughness of this trade, does not seem like a viable option for younger Greeks, who are not only abandoning the fishing way of life but also abandoning

the islands and villages for the big city.

“Fishermen have swallowed the bait of the EU, and become fish themselves,” concludes 55-year-old Kostantinos Stratis, commenting on the financial crisis which has taken its toll on the mainland while small businesses die for the sake of globalisation.

Stemper’s LUPIMARIS diptychs are without doubt one of the last impressions modern society will have of Greece’s ‘wolves of the sea’. Black and white, weathered faces juxtaposed with their colourful boats create a unique entendre, a dual reality. On the one hand, sea-beaten men, wrinkled by hardship, and on the other, small, wooden vessels, barely staying afloat. Both bearing the same marks. Marks of the times. Christian Stemper is a photographer based

in Vienna.

To buy his book (€49), prints and postcards head to lupimaris.com