Once synonymous with suffering and death, Spinalonga, the jewel of Mirabello Bay, has risen to world fame through Victoria Hislop’s international best-selling novel, The Island – and the subsequent TV series, now regarded as the best fiction program in Greek television history. Building up to this cultural momentum, a movement was started with the intent of making the Elounda island famous around the world, claiming its place among the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The nomination was submitted last autumn, and it is now entering the final stage, which offers a great opportunity for the series cast and crew to revisit the island and express their support.

“This historical monument was based on the foundations of the Minoan Era”, says Antonis Zervos, mayor of Aghios Nikolaos, and a strong supporter of the cause. “It was very cleverly built and used as a strong fortress using an elaborate defence philosophy, unique for those times. In addition to this legacy, Spinalonga promotes human values. Our nomination file also stresses all the hard work needed for restoration in order for the epic island to not suffer.”

The Greek Ministry of Culture offered a budget of €6,000,000 for the monument’s maintenance. However last year the ticket price to enter was raised from €2 to €8 “due to an influx of tourists”, the mayor points out.

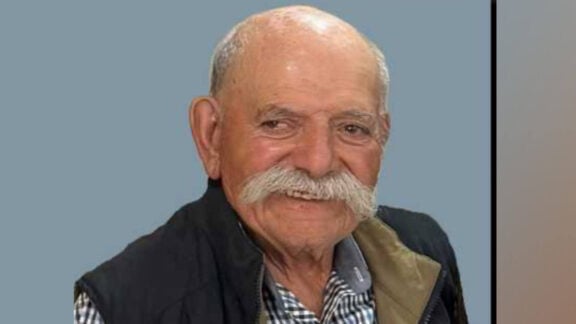

From his part, the series’ director Thodoris Papadoulakis shares his vivid memory of “the Exodus scene, with Victoria Hislop embracing the late Manolis Foundoulakis, who was in fact, the last resident of Spinalonga suffering from the Hansen Disease. He sadly passed away before the TV series premiere four years ago. On that last shooting, Manolis finally felt free from his curse”. However, before his demise, Manolis Foundoulakis had the chance to watch the first scenes of the series before the final cut. They were specially presented to him and he was very moved. The Island was dedicated to his memory.

For Margarita Panousopoulou, who played the part of Kalliopi, the series was an opportunity for her to walk through Cretan customs and culture. In fact, for her role she was taught how to weave using the traditional Cretan loom.

But it was the emotional lesson that still lingers on, as she realised, through her participation in the series, how “leprosy is still considered a curse, even nowadays”. It was through her interaction with the late Manolis Foundoulakis that she understood what it means to be cursed and exiled in Spinalonga.

She admired the Cretan people “for strongly supporting their beliefs and customs till the end. Crete remains always a symbol of fertility” for her.

Playing an outlaw who desperately tried to keep her healthy baby from forced adoption at the hands of the authorities – which was the norm during these dark times – Margarita herself remembers how she was encouraged by Victoria Hislop to ‘escape’ from the emotional toll that the shooting had on her, fondly remembering joining the author in hijinks with raki and the enthusiastic local joining them with signature Cretan kefi!

Anastasia Tsilimpiou also retains fond memories of the locals, “the sweetest kind of people on earth … [who] were full of pride and honour by the fact that we came to work on their land”.

The young actress still remembers collapsing into tears at the scene of her TV mother stepping down the rocky dock to board the boat on her way to exile, led by her husband. Anastasia still recalls the feeling of the grey atmosphere that really got her as well as the rest of the crew.

She was filled with awe when she first saw Spinalonga. “I thought that I had the chance to go there and return, while some others left with no hope of seeing their families and homes again”.

This kind of hopelessness is what makes The Island still relevant, even though Hansen’s Disease no longer bears a stigma.

In a way, there is a similarity between the leprosy patients exiled in Spinalonga and the refugees who are fleeing from war-torn countries and hardship and finding themselves on the Greek islands.

Alexandros Logothetis, who played the charismatic doctor, does not agree. “In many ways, I would almost say that they are opposites”, he says.

“The leprosy patients were exiled to Spinalonga, many taken by force, to spend the rest of their days, without hope and without treatment, until successful therapy was found. Many of them lived for years there, the majority never left. It was the end of their ‘travels’. Many of the refugees who are being helped ashore in the Aegean islands are also desperate, but in a very different way. They have also lost everything, many of them have lost a whole family.

“But they are there because they still hold on to the hope of finding a better life. For them there is the possibility of a new beginning, as opposed to the leprosy patients, for whom Spinalonga would have been perceived as an ‘end’. The refugees in Greece are being helped by the residents in amazing and heroic ways. They may at some stages of their journey also suffer from the stigma of being refugees but for them one hopes for a better future. Their time on the Greek islands will not be for long if they can make their way to countries where they can start a new life,” Victoria Hislop adds.