What one will find trending on social media 24/7 is an online stir on trends that are perceived to be appropriating culture.

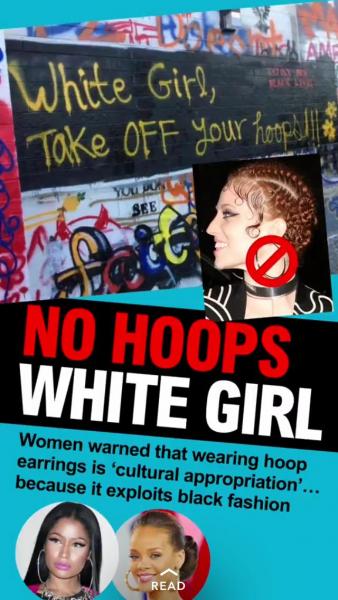

‘White Girls, Take Off Your Hoops’ says graffiti gone viral. I say keep them.

In April, New York’s Whitney Museum opened its biennial exhibition of contemporary American art. Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket featuring a famous photograph of a dead black boy, Emmett Till, who was tortured and beaten to death in the mid-1950s, received major backlash. Schutz’s crime was her Caucasian identity. Numerous petitions and comments surfaced with demands that her “abomination of a painting” was taken down or even destroyed for the “garbage that it is”. The artist’s intent, meanwhile, was “to honour black lives that matter” by paying tribute to the little boy’s death. She was instead accused of “appropriating an issue that has nothing to do with white people” with hate comments climaxing and birthing yet another argument on “why Caucasians are exhibiting and even wearing Indigenous cultures’ garb”.

But what is ‘cultural appropriation’ anyway?

One has to go as far as to appropriate several explanations in an attempt to cohesively describe what it is, as well as what it is considered to be, by certain millennials.

While cultural appropriation typically involves members of a dominant group exploiting the culture of less privileged groups – often with little understanding of the latter’s history, experience and traditions, these days we are seeing individuals from certain ethnic groups lashing out against fashion designers, performers, artists, stylists, hairdressers, and so on for “culturally appropriating” styles, features and sometimes issues that are ingrained with a race’s history.

Cultural appropriation is inherently wrong; the need for a red flag, a mark where one can actually draw the line becomes more pertinent in this time when philosophical questioning and attestation of universal truths, dare I say freedom of speech itself, is in danger of becoming extinct, for fear of offending those who freely voice their ‘declaration of being’, their definition of oneself, their self-categorisation or their opposition to fall under categories whether said categories fall under politics, ethnicity, sexuality, you name it.

The last couple of years we have been hearing at rising volume that white women are not supposed to wear their hair in dreadlocks or swirls; style their baby hairs; do a full cat-eye makeup; and, as of this month, white women are not supposed to wear hoop earrings.

The latest victim of the online fury was acclaimed designer and father of the 90s youth culture street style, Marc Jacobs, who dared to “appropriate” the accessory on his latest collection’s catwalk. The designer has stated many times that street culture is his ever-giving source of inspiration, however, no one can deny the decades of influence he has exerted on ready-to-wear fashion.

What spurred this recent fiery debate, is graffiti on Canada’s Pitzer College’s free speech wall; a plain brick wall on which Claremont students freely vent their opinions and feelings with spray paint. Students Alegria Martinez, Jacquelyn Aguilera, and Estefania Gallo-Gonzalez, in defence of brown and black culture freely painted: “White Girl, Take Off Your Hoops!!!” in yellow, taking away a white woman’s right to wear the much-hyped accessory.

“The art was created by myself and a few other WOC [women of colour] after being tired and annoyed with the reoccurring theme of white women appropriating styles . . . that belong to the black and brown folks who created the culture. The culture actually comes from a historical background of oppression and exclusion. Because of this I see our winged eyeliner, lined lips, and big hoop earrings serving as symbols as an everyday act of resistance, especially here at the Claremont Colleges. Meanwhile we wonder, why should white girls be able to take part in this culture (wearing hoop earrings just being one case of it) and be seen as cute/aesthetic/ethnic. White people have actually exploited the culture and made it into fashion,” Martinez, a member of the Latinx Student Union said, explaining her act in a statement to the entire student body as reported by the Claremont Independent.

In August last year, Pitzer College made headlines when students refused to room with white people bearing or as stated at the time “appropriating styles that belong to the black and brown folks” and “exploiting the culture.”

“If you didn’t create the culture as a coping mechanism for marginalisation, take off those hoops, if your feminism isn’t intersectional take off those hoops, if you try to wear mi cultura when the creators can no longer afford it, take off those hoops, if you are incapable of using a search engine and expect other people to educate you, take off those hoops, if you can’t pronounce my name or spell it . . . take off those hoops / I use “those” instead of “your” because hoops were never “yours” to begin with,” Martinez added to what, in my eyes, reads as completely absurd, as she herself failed to use a search engine; but maybe she will accept to be educated by other people who won’t go as far as to ask her to “take off those hoops”.

Furthermore, a few weeks earlier actress Lucy Hale from TV show Pretty Little Liars, who happens to be white, tweeted a photo of herself with a caption that read: “The time my baby hairs came to good use at a shoot,” wearing the trendy hairstyle that celebrities like Rihanna, FKA Twigs, Zendaya, Yara Shahidi and back in the 90s Chilli from funk R&B band TLC often donned. Katy Perry was also found guilty of cultural appropriation for wearing her hair the same way; “How dare she? Enough with this white, rich women thinking they own everything”, a tweet said.

While I personally, as a descendant of Greek migrants who on one side fled Asia Minor to escape the genocide and on the other ran and hid to avoid persecution simply for being Jewish, have the utmost respect for oppressed ethnic groups and trying to preserve and protect one’s cultural identity, I find myself unable to agree with the women of colour claiming cultural rights of the styles in question.

Without wishing to reduce the struggles for equality of brown and black people, I can’t but see us all as people of colour. As appalled as I am when I come across ideas of white supremacy, or racial supremacy of any kind, I’m equally put off by the reactive hate certain mentalities are spreading; unintentional as it may be, it still is harmful.

Agreed, wearing your baby hairs sleek and proud on your forehead, with the rest of your hair pulled back in defined curls or a bun, or swirls or cornrows with a statement pair of hoops is a thing of the 70s, celebrated by African American ghetto queens and ‘Fly Girl Latinas’, made famous by icons such as Pat Davis and Fawn Quinones in the legendary Soul Train, LaToya Jackson, Sylvia Robinson, and even Mr Giniwine, a soul legend of the time. Agreed.

“Growing up in the eighties and nineties, wearing the latest hair trend, while sporting baby hairs was synonymous with the ‘Fly Girl’ phenomenon,” explains acclaimed publicist Colleen Gwen Armstrong. “Times may have changed, but the ‘Fly Girl’ phenomenon continues as baby hairs continue to represent a symbol of beauty within the black community.”

It was a style of the 70s but if we choose to go back and claim ownership over ‘style’ and external, cultural traits of choice why not go back all the way?

I would have to object: as this baby hairs style was extremely popular with 1920s women in Europe and America, often combined with the iconic flapper dress, glossy red lips, and over-plucked pencil-thin eyebrows. I’ve seen it in many well-preserved family photos.

Those hoops you are so fiercely asking to be taken off the ears of white (I’d rather say non-black and non-brown-skinned) ladies have adorned the ears of Greek women for over 4000 years, along with those baby hairs, styled exactly as today’s WOC are wearing them.

Greek women had swirls and sometimes cornrows too. As for the makeup: next level full cat-eye. The eyes though, we most likely appropriated from the Egyptians who have a recorded history of 6000 years practicing it; they never accused us for culturally appropriating them, however.

Those cultural characteristics, deeply ingrained and imbued in Greek civilisation, for thousands of years evolved, yet remained evident, throughout our cultural expression in different ways depending on the region.

Women in the Dodecanese, Epirus, Macedonia, and central Greece kept them alive, even under Ottoman occupation, in many villages to this very date.

However, as I write these lines, I can’t help but feel conscious of my standpoint and what criticism I might receive for mentioning skin colour so many times in this text, being a very pale Caucasian-looking person.

Cultural appropriation and exploitation of non-prevalent cultures in dominant societies does exist and ethnic groups, non-white ethnic groups have been taken advantage of. Racism and discrimination still plague our society and we are all guilty of it, one way or another. Answering to hate with hate, or wanting to own a tradition or attribute a style to an ethnic group based on its people’s colour, especially when we are not fully aware of another ethnic group’s cultural history is wrong.

Style is not a competition; race isn’t either. Fashion is art and there is nothing more mesmerising than the power fashion has to let such trends emerge. As much as some people opt to see ethnic traits interpreted as ‘copying’ or some sort of “shameful act of social ignorance and cultural disrespect”, these trends that have us arguing lately about whether they should be essentially tied to a specific ethnicity or not, are actually doing more good than harm. They are making people aware of other cultures’ heritage, they are celebrating cultures. It is not the designer’s intention to ‘steal’ a group’s racial identity as I refuse to see a person’s personal expression, a person’s choice of style, to be mal-intended with an aim to undermine another individual’s culture.

However, if we choose to see this as a game or a fight of ‘mine and yours’, these styles are more ingrained in my and my people’s sense of cultural identity that yours. And Greek people happen to be predominantly white.

Does this give me the right to ask FKA Twigs to stop appropriating our 4000-year-old Minoan style? Because in my eyes and based on what I have been exposed to, that’s what her signature style looks like. And it suits her. She owns it.

Will I ask a Latina or an African American to “take them hoops off” because Greeks did it first?

Should I lash out against all the Anglos in Australia walking around with evil eye bracelets around their wrists?

Wouldn’t it feel wrong if Swedes were to complain about Arab and Indian women having blonde hair?

What if the English, Scottish or Irish forbade Greek and Italian schoolkids to wear their signature tartan in Anglo societies?

If we are supposed to live and express ourselves only within the specific culture we hail from then, there should be no advocacy for unity and equal rights.

Judging an individual’s social behaviour and appearance on the grounds of abstraction is almost like running backwards towards the dark times we all wish to put behind us. It’s not forward thinking.

Segregating people on the basis of which racial group they happen to be born into is divisive and counter-productive; it is racism.

No one is ‘stealing’ anyone’s ‘cultural pride’; at the end of the day nobody should feel more proud than the other. As racist as it is to not allow an individual to partake in an activity because of their skin colour, it is racist to ask a white woman not to wear this or that because in your culture it is linked to a specific memory, that of oppression for example.

Think again. ln someone else’s culture – a few thousand years older than the date your trend was born – this trait symbolises fertility, it celebrates beauty, and views women of the world as reflections of mother Earth, Gaia.

We are all unique individuals, with the freedom to discover and embrace different things, and this very freedom to express our own personal truth and perception of beauty in the way that resonates with us the most is what makes us human.

Taking the smallest freedom away from a certain group and only allowing it to the ones who claim it in the name of preserving ethnic identity, does not empower or liberate anyone from oppression and racism; it is a paradox; it is spitting in the face of what you stand for.