Google Peter Polites, and time again you will see him likened to writer Christos Tsiolkas. And to be frank, as a fan of Loaded it was this descriptor that first inspired me to pick up a copy of Polites’ debut novel Down the Hume.

But the more I read, the more I was let down, and to a certain degree Polites was too. For though Tsiolkas is a talent to be revered, the debut novelist very clearly has his own voice and with each page the connection instead seemed to be an easy, and almost lazy, way of collectively grouping two writers of Greek decent who explore ethnic and same-sex identities.

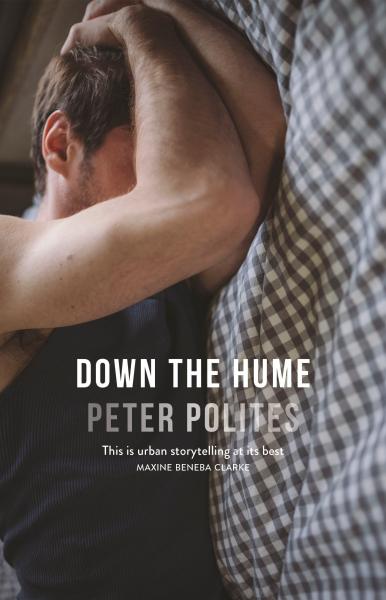

Down the Hume follows the story of a young gay Greek man by the name of Bux who is in an abusive relationship, lacking in both trust and intimacy, with a man endearingly termed ‘Nice Arms Pete’.

Set in working class western Sydney, with each chapter named after streets in the area, Bux’s life revolves around working in a nursing home and battling his demons with an addiction to painkillers; a habit he can’t seem to kick made all the worse by his aptitude for self-destruction.

Given the obvious connections between the writer and his protagonist – both Greek, gay and from western Sydney – as a reader you can’t help but wonder how much of Polites himself is on the page.

“Oh heaps. It’s me, if I only make 10 per cent of decision-making processes,” he reveals, adding that whenever it got too close to home he reverted to the metaphors running through the novel – white Australia and migration.

“It’s also about the relationship between the children of the post-World War II migrants and white Australia because our parents came here for a very specific reason; they came here because they were a part of a nation-building project and we’ve come into a very different Australia than they had. We don’t have the same economy that they inherited, we don’t have the same jobs that they had, and so it was about exploring that as well.”

Throughout the narrative, Bux grapples with his identity, feeling as though he doesn’t quite belong anywhere; not in the gay community, not the Greek community, nor his workplace – themes which come straight from the heart for Polites.

Born and raised on the outskirts of Sydney heavily populated by migrants, the writer says he never really felt Australian. That is until now, at age 37, a revelation he reached through the process of writing his novel.

“When you’re a writer from a minority background sometimes you need permission to write.

“I always had that left-wing thing of going ‘I am a citizen of the world, and of humanity and citizenship’ and then I think after I wrote this book I realised that I am fully Australian, and that’s not a good thing or a bad thing; it’s not something I’m proud of, it’s not something I’m ashamed of. It just is that, you know.”

In broader society Polites says he always knew he was different. Having come from a migrant family he says what also set him apart from the Anglo-Saxons was that he was socialised differently. With consumption low on the agenda, one example he cites is that his family never travelled for the sake of exploring, only with the intent to visit family or for work.

Meanwhile the gay community hasn’t been any easier to navigate. In his experience he says that southern Europeans and Arabs of a particular physical type are often treated as the ‘other’.

For his novel, which took some seven months to write, he set out undertaking extensive research and observing the inner workings of his surrounds.

“I looked at all the gay men in my community that only date white Anglo-Celtic men and refuse to be associated with men from the same community or from other ethnic communities. It’s one thing I’m surprised people haven’t commented on, the fact that it’s hard to find white boyfriends in western Sydney but this character just seems to do it,” he says.

Through Down the Hume Polites also provides commentary on the complexities of low socio-economic groups, bringing to light the abusive side of relationships, highlighting its prevalence within the gay community.

“A lot of my friends are low socio-economic from queer/same-sex attracted background or culturally diverse backgrounds and I’d say more than 50 per cent of them have been in a situation of same sex domestic violence and that’s a lot to have in a friendship circle,” he says.

“There’s a complexity to same sex domestic violence because you’ve got this powder keg of minorities that are disenfranchised. You have the minorities who can’t come out to their family about their sexuality; there are minorities who have to witness structural violence and a lot of the time the violence has to manifest physically in forms in the closest people around you. So what I’ve seen is that people who are disenfranchised in a cycle of violence perpetuating that cycle of violence,” which he notes is also a problem within the Greek community given the general notions of masculinity held by migrants, which he once again attributes to social and economic structures.

“We have inherited really bad notions of what it is to be a man, and these hyper-masculinist notions of masculinity. There’s this complex duality in Greek culture where I think the mothers coddle the boys. But at the same time there’s these expectations of masculinity.”

While Polites says that as a community Greeks often seek too much legitimisation from authority figures, he says enough credit is not often afforded to people concerning their ability for change and progress.

Where his protagonist is cast out by his father after coming out, Polites notes that his own experiences and dynamic with coming out to his parents, while not without its challenges, evolved quite differently to that in the book.

More recently, Polites has been busy with the 2017 Sydney Writer’s Festival, commissioned by Urban Theatre Projects to write the performance text Steps into Katouna. He praised the festival director, citing the event as one of the most diverse he has been too and one which challenged and highlighted his desire to continue learning from those around him.

“I learnt a lot from other participants but also I learnt how far I have to go to become a good talking head, and also that there are significant gaps in my knowledge. That was made prominent to me and I’m hoping to learn as much as I can,” with regards to the complex relationship Indigenous Australians have with the 1967 Referendum and the issues surrounding trans and queer individuals when it comes to labels.

At which point in the conversation, I start to realise my own limitations in assuming the orientation of ‘gay’ for Polites.

“Queer to me is a very theoretical framework, whereas gay is an economic indicator now. So for me I use it in the sense that I’m same-sex attracted. I think the only thing we can do is maybe ask people and listen.”

And it is with this same consideration that Polites has approached Down the Hume, offering his readers a confronting representation of life and the role we play in our own self-destruction.

While Down the Hume does provide commentary on the inner workings of the gay community, it’s important to note that Polites’ protagonist’s sexuality is almost secondary – as is quite often the case when writing about heterosexual relationships – and the novel’s themes relevant to the majority.

“That’s what my goal is,” Polites admits.

“I think there was a real period of queer literature that purely existed in the realm of queerness and I think in a post-HIV world there’s a different notion of what it is to be queer and I think queers are as part of the tapestry of Australia as anyone else.

“Some people have been like ‘you’re showing gay people in a very negative representation’. And I’m like no, it’s complex. It’s a complex representation. There’s lots of joy there and laughter as well, and that’s how you get through the bad things.”