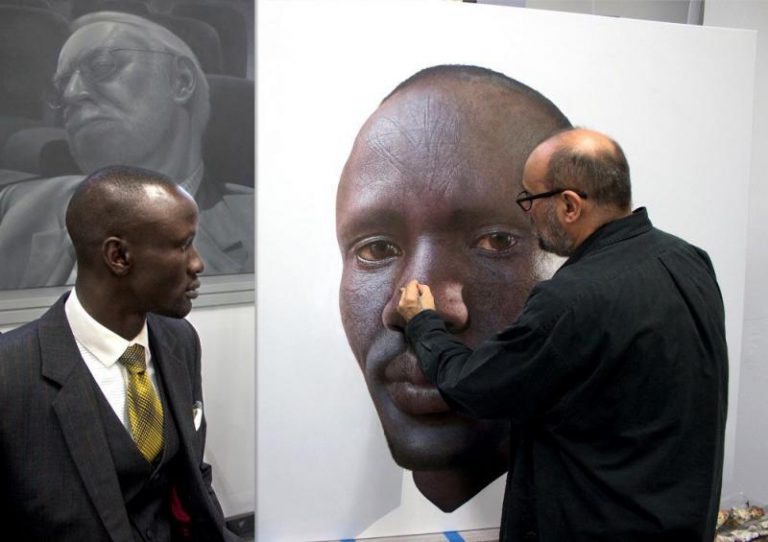

On the cover of Let’s Face It: A History of the Archibald Prize which narrates the almost-100-year journey of one of Australia’s most coveted arts prize, there is a picture of Nick Stathopoulos’ portrait of Sudanese refugee lawyer Deng Adut. What makes this worthy of mention is not the portrait’s lifelike accuracy – Stathopoulos, after all, is known for his mastery of hyper-realism – nor the power of the subject itself, but the fact that this portrait did not win the prize. One cannot but wonder why the editors did not choose an actual winner, but in a way, the history of the prize is also a history of controversy, of worthy finalists failing to make it to the top and of a parallel prize, aptly named ‘ Salon des Refusés’, featuring the works which did not make it to the finalists, competing for the ‘People’s Choice’ award. Stathopoulos won this award last year, for his portrait of Deng Adut, as he had done a few years ago with Ugly (portrait of author Robert Hoge). In fact the self-taught painter, who has been working as an artist for over 30 years in film, television, animation, and book publishing, has made it five times to the Archibald finalists, but has yet to win. “I’ve been described as the Hillary Clinton of the Archibald – she won the popular vote, but didn’t win the election”, he humourously revealed in the Foxtel Arts documentary The Archibald which follows his (and other artists’) forays into the 96-year-old arts institution.

How did it feel, having a television crew follow you around and documenting your work?

Having the crew there didn’t really alter anything in terms of my way of painting. But I had to be more conscious of the timeline and pace I would normally work at, because the crew needed to capture those pivotal moments as the painting evolved. Watching paint dry doesn’t make for particularly interesting viewing. But they did document my entire painting process. Watching my painting evolve in time lapse is fascinating!

What would winning the Archibald Prize mean to you?

Now this is a question I was asked a couple of times by the crew. I used to read about the Archibald when I was a teenager. It always held an allure, a mystique for me. So to win it would be like a childhood fantasy come true. But I don’t enter the prize to win. I enter predominantly to have my work seen. Of course, it would be a tremendous boost to my career to win the prize. And the value of all my paintings purchased in the past would be enhanced!

Who do you think is the most unfairly disregarded Archibald Prize finalist?

In these times, when gender equality is such an issue, I’m appalled that artist Jenny Sages hasn’t won the prize. Having been hung twenty-three times to date, she really should have taken the prize out in 2012 with her self-portrait titled After Jack – an extraordinary and deeply moving depiction of grief following the death of her devoted husband. She is now in her mid-80s, and no longer enters the prize to my dismay. This angers me greatly.

Which is the best-deserved work to be awarded the prize?

Most of them. Not all of them, but most of them! I do have some personal favourites, though. I’ve always held a soft spot for William Dobell’s Joshua Smith. Although the win came at a great personal cost to both artist and sitter, it did burst open the stuffy doors of the AGNSW to more contemporary forms of portraiture.

What makes a great portrait?

I think there has to be a connection between the artist, the sitter, and the viewer. The portrait has to ‘speak’ to you. It has to have life …ζωή. It also has to have artistic integrity, which is something harder to define. But most importantly, the artist has to be true to themselves, to their personal vision. You can see this in portraits where the same subject has been painted by various artists over the years, and each one is an idiosyncratic portrayal.

How do you decide the subjects of your portraits?

I have a wishlist! Mostly they are people who I admire and have some kind of connection with. I might know them personally, or they might be people whose work I love and relate to. But once they’ve been painted by somebody else, and that painting has been a finalist, I tend to lose interest.

How would you describe your relationship with the people whose portraits you have painted?

What I love about the Archibald – and the fact that I’ve been hung a number of times now – is that it grants me license to approach potential sitters. I get to meet the most incredible people. But the actual painting process, the sitting, requires an act of trust on the part of the subject.

When I told David Stratton that I wanted to paint him asleep in a cinema he said “You’re the artist!” and let me do my thing. That’s liberating, but there’s still a lot of pressure. I try and honour the sitter with the best possible painting I can create. I hate having to contact the sitter when the painting doesn’t make the finalists. I feel like I’ve failed them.

Who would you like to paint your own portrait?

I’ve already been painted a few times. I was asked to sit for this year’s Archibald, but with all the dramas and time pressures of the documentary, I had to defer the sitting. Honestly, I hate seeing myself. I have immense difficulty watching myself on TV. But a painting is OK, probably because it’s distilled through another person’s impression of you.

What makes you an artist?

Oh, I’ve always been an artist. It’s genetic predisposition. I won my first art competition in kindergarten. I used to win all sorts of art competitions when I was growing up.

How did you first realise the power of your art?

I have a vivid memory of having to draw something for Book Week when I was in kindy. While the other kids were struggling with their crayons, I painted my teacher bending over to take a book off a shelf. I still remember the astonished look on her face.

How would you describe your artistic journey so far?

It’s a continuum. I’ve always been involved in some creative activity. I’m now more focussed on my fine art. I’ve had to narrow my diverse artistic practices due to the practical realities of life. But I’ve been pretty lucky in being able to exercise my passion on a daily basis.

If you were not an artist, what would you have become?

I have an ancient degree in law, and always harboured an interest in intellectual property, but to be frank, I can’t not do what I do now. If I go for long periods without painting, I become physically ill. It’s that deeply ingrained into my psyche. I’d love to make more films. I love puppetry and animation. I love illustration. But I only have one life.

How do you relate to your Greek background?

Hmmm. How can I explain this? It wasn’t until I visited Athens for the first time in 2009 that all the pieces fell into place. All the places my grandparents talked about suddenly became real. It’s like some distant race memory suddenly kicked in. Have you ever seen those lists of last meals by deathrow prisoners? On my list I’d have my mother’s κεφτέδες (meatballs). But I can’t say being Greek has influenced my art. I didn’t grow up with any famous Greek artists as role models or anything. But I do listen to Vangelis while I paint!