“If we think only about ourselves, that short-changes us as individuals and lessens us as a society, it keeps us all back. We need to work together.

In the backroom of the Federal Member for Calwell’s constituency office, her team are busy.

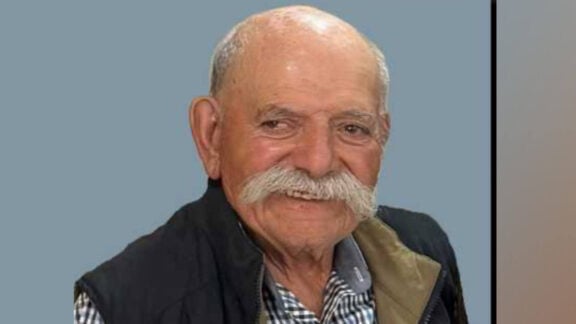

Knocking up election placards, volunteer Louie Josef feels the single wooden posts might need extra strengthening in the wild and windy parts of the electorate, which stretches from Taylors Lakes to Craigieburn.

With a science degree – Louie, a recently-arrived refugee (under the humanitarian program) from Iraq – is more than qualified to handle the critical mechanics of old-time electioneering.

Maria’s right-hand staffer Marianthi Kypuros is at her desktop – managing the usual heavy load of constituency enquiries, while another volunteer, Janet Curtain, is handling the diary, ensuring that her boss can get the most interactions in the weeks ahead with the people who will decide Calwell’s election fate.

Maria and I head across busy Pascoe Vale Road, past the Hume Global Learning Village to the Broadmeadows shopping centre; the mall serves up a perfect slice of life for this outer metropolitan suburb.

Women in hijabs with prams hurry past, joining the morning shoppers as I pry into where Maria’s political education began.

“It was in high school. In 1975 I was at Princes Hill in Carlton. It was an exciting place to be, very multicultural,” she says.

“My father worked constantly. In the early years he was at General Motors and then a labourer – it was a typical migrant’s story. Dad had two jobs – day and night.

“He used to work at Myers as a cleaner for many years so we only saw him for about an hour a day.”

Exposed at an early age to the circumstances that had forced the Vamvakinou family to leave Greece, Maria says informal history lessons were part of everyday life.

“I learned a lot about the Depression, about poverty and the German occupation of Greece, the Jewish Holocaust. They were the stories I was brought up with in the ‘sixties, directly from my parents and my uncles and aunts.

“My mother, who never had the opportunity to be educated and was taken out of school at grade 4, never really wanted to leave her village in Lefkada.”

Like many politicians from a migrant background, the Vamvakinou family’s journey to becoming Australian defined a curious daughter’s political path, and a natural inclination to the left.

“I was always actively interested in what was going on around me. I’m in politics because I don’t mind my own business, that’s the best way I can describe it.”

For Vamvakinou the traditional values of the Australian Labor Party offered the only course to deliver a responsible, caring society. And it’s those values that she says still define the difference between Labor and the Coalition.

“We’re not a party of the individual, we’re a party of the collective,” says Maria.

“We’re a party that looks at how to help lift people out of disadvantage – a party that has a commitment to social justice – these are the values that drive our polices. Giving everyone a fair go, and giving those who perhaps are not fortunate to be born into an opportunity.”

With a comfortable majority at the 2010 federal election – Vamvakinou won 49,580 votes to the Liberal’s 22,556 in first preferences, and 61,000 to 26,500 in two candidate preferred – it’s highly unlikely that Maria’s heading anywhere other than Canberra after September 7.

“It’s a traditionally safe Labor seat, but I don’t take anything for granted,” she says.

“I’ve seen changes in the political climate that I find worrying. Younger people – are they less interested than my generation? Probably yes. People are viewing political allegiances differently today.”

A typical working class suburban electorate, Calwell has a diverse constituency of older migrants and new emerging communities.

“The aging of the Australian community is reflected very strongly here,” says Vamvakinou.

“Their issues are good aged care. I have the biggest Italian-speaking constituency in Victoria, a lot of the old Greek and Yugoslav migrants and they’re all in their seventies and over.

“I’m one of the second generation that has to think about what I’m going to do with my elderly father if he needs to go into a nursing home. Am I too busy to look after my parents?

“These are the things my generation in this electorate are dealing with, who may not necessarily be voting Labor, because my generation is also shifting, but ultimately they’re making these decisions – and government needs to respond.”

Vamvakinou’s electorate also embodies another contentious issue on the current political agenda.

The home of Ford Australia – which will close its production line in 2016 – Calwell reflects the debate around the terms of any Australian government’s support for the automotive industry.

“We’re committed to investing in the automotive industry because we believe it has a future and we believe that we need to sustain it.”

Vamvakinou points to the North Innovation and Investment Fund as proof of Labor’s commitment to supporting manufacturing in the area after Ford is gone.

To be provided jointly by federal and state governments – with the lion’s share coming from Canberra – the fund will see $25m pumped into the area over three years to help businesses diversify.

“We’re putting money into helping people grow,” says Maria.

With Labor extolling the virtues of ‘A New Way’ – the party’s election slogan that neatly consigns the party’s recent destructive internal wranglings to history – will the electorate forgive Labor’s sins over the past three years?

“I’m a realist, I don’t think it’s going to be easy for people to forget a lot of what happened, things that were difficult for us as a party,” says Maria, who actively supported Kevin Rudd through thick and thin – as PM, after his removal, and then in his resurrection.

Asked what mistakes Julia Gillard made that led to her downfall, Vamvakinou says it all stemmed from Rudd’s removal as prime minister in 2010.

Does she have empathy with Julia Gillard?

“I don’t want to speak about Julia as an individual because she operated within a collective. The mistake we made as a party is we took it for granted that people would not have a view about the removal of Kevin Rudd.

“The public’s reaction was that they were appalled, people in the party didn’t give enough weight to that reaction. We never recovered from it. We’re not immune from being judged.”

One judgment of Vamvakinou’s is that Gillard took the party on a journey that revisited old ground with some unhelpful socialist vocabulary – the notion of class struggle.

“I wasn’t comfortable with that approach, and I come from that background. There was a return to the political battleground of Labor decades ago,” says Maria.

“Evoking that kind of language wasn’t an appropriate thing to do, to a community that hadn’t heard that kind of language for quite a while.

“That doesn’t mean that class struggle in Australia has disappeared and that the rich aren’t getting richer and the poor aren’t getting poorer. But the language of today needs to be different. Things have changed. You have to find different ways of addressing the same issue.”

And Julia Gillard’s legacy? “She did an incredible thing: she became Australia’s first female prime minister. Education, disability – these are major reforms and are significant achievements.”

How hopeful is Maria that on 7 September, the Labor Party – seemingly destined just weeks ago for political oblivion – will be returned?

“I’m cautiously optimistic,” she says. “It’s going to be close and it’ll come down to a handful of seats. The electorate are looking for some stability in terms of their value systems.”

And if the electorate turn to Mr Abbott for that stability?

“For my community I think it would be very damaging if an Abbott government is returned. The reality is, they’re likely to make savings and cut programs – and usually those savings are in areas that people like my constituents benefit from.”

For the undecided, Maria’s message is to go beyond individual gain but to look to the bigger picture.

“I think undecided voters should think very carefully, consider what’s on offer for their community.

“If we think only about ourselves that short-changes us as individuals and lessens us as a society, it keeps us all back. We need to work together.”

As a mother of older children, Maria’s last comments are ones no doubt shared by parents of all political persuasions.

“I have an 18-year-old and 20-year-old and they’re the ‘me generation’. I don’t like that whole focus on ‘me, me me’,” she says. “You want them to understand that it’s not only about them, it’s about everybody – family, grandparents, friends.

“In Greek tradition the extended family is the model for a community – it’s not about individualism, it means we look out for each other.”