Finishing high school felt like such a relief. I could not wait for liberation from uniforms and the cloistered classrooms built around the design of a Union Jack.

Little did I know how closely connected I was to remain to some of the ideas and people that had shaped me in that school. To this day I do not complete an idea until it has been cross-checked by my friend Scott who has been beside me since were 12.

It was at high school that I read the poetry of Sylvia Plath and became conscious of the other worlds that were formed in the state of being an outsider. Staying connected to people who share your values and turning thoughts inside out has been the most valuable lesson in my life.

Peering over the school fence

Let us now look over the school fence and see what the rest of the world can offer. The day I turned 18 I passed my driver’s test and attended orientation week at Melbourne University. I thought I would mark this transition by buying a wallet. I did not own car and was not used to carrying a wallet in my pocket. After purchasing my ticket for the train at Balaclava Station I promptly left the wallet on the bench. I arrived at university with no cash. It was annoying but in those days that is all I lost.

Inside the university welcome bag was a cartoon by Michael Leunig. It depicted his celebrated figure – a young man with an over-sized head and a bulbous nose – standing at a crossroad with two signs pointing in opposite directions.

“Carlton – this way.”

“Rest of the World – the other way.”

I felt happy to have escaped.

Earlier on in the summer, I was briefly tempted to go the other way. I was working the night shift as a storeman and packer in a Port Melbourne warehouse. The crew in the warehouse consisted of people from three different nationalities: Mauritians, Greeks, and New Zealanders. The Mauritians were my neighbours in St Kilda and drove me to work. During the lunch break at 4 am I ate my mixed grill with the Greeks. During the hourly ‘smoko’ breaks I sat in booths with Kiwis and talked rugby.

Gabriel and Dave were two drifters who appeared in a lime green holden panel van. Gabriel was cool, only spoke when he had something to say, and was better looking than Richard Gere. Dave was short, tubby, and a total loudmouth. When I mentioned that I was about to start at ‘uni’, Gabriel groaned, and Dave blurted.

“Why would you do that! Just hang with us. We are heading to the Gold Coast next.”

I said nothing. I was caught in the rip of these guys and my dreams.

My uncle George had lived this life. When we watched the film “Midnight Cowboy” – where Jon Voight plays the role of a country boy who comes to New York to chance his arm as a gigolo – George said: “this is the story of my life”.

The fantasy of the road trip

I fantasized about being on the road, but I also saw myself as someone who lived more and more in his mind. During that ‘smoko’ I sat stuck between Gabriel and Dave. I had no words of my own. Dave kept raving on about the adventures in coastal towns. I could no longer hear anything he was saying. I was captured by the long stare in Gabriel’s eyes. He was neither approving of ‘uni’ nor arguing against it. I was aloof to the shame of throwing away an education but also needing something more. Joining them was enticing but it did not fit with the pattern that was starting to form inside of me.

How do we work with that bundle from which decisions are made, or what the poet Antigone Kefala called, “the measure inside us”?

These little moments can seem trivial, obscure, and idle, but they are turning points. So much is spinning, so many different options are screaming for attention, and yet, amidst this chaos some kind of path is also visible.

A famous author once said that the hardest thing he ever faced was explaining to his wife that, when he was sharpening his pencils and staring out the window, he was working. Recently, I was writhing from the conflicts between reason and passion. I blamed myself and struggled to forgive myself for falling and turning over and over with the same arguments in my head. My friend Martin reminded me of George Bernard Shaw’s great line: “a puritan is someone whose mind has never had a holiday”.

For me a holiday is when my writing is going well. I love the adventure of imagination and the control in thinking. However, Martin’s comment was a poignant reminder that letting go was neither weakness nor fault.

Plato and Aristotle and the importance of leisure

In Plato and Aristotle’s writing there is no mention of holidays or the sharpening of pencils. However, they both talked about the importance of leisure. Today we contrast leisure time to labor. For the Ancients leisure was linked to the radiance of cosmic virtue and contrasted with political life. Labor, or working to ensure the bare life, was far below. The good life needed the time of leisure, not for the purpose of sitting by the pool and drinking cocktails, but for the space to reflect, speculate and experiment. Without leisure there is no pause through which those other thoughts emerged.

It should also be recalled that the ancient polis was not marked by the conspicuous accumulation of private wealth. There were slaves who did the menial work, but there were no palaces and mansions.

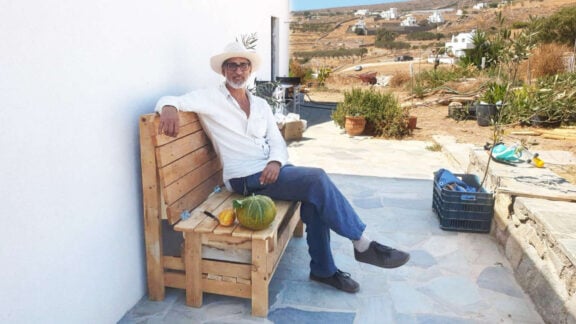

Aristotle claimed that by using reason to shape common values ‘man’ became a ‘political animal’. The trickster philosopher Diogenes also stressed that freedom was most exquisite when one planted and took care of one’s own vegetables.

To be an active citizen you had to be free of debts and detached from material self-interest. Thus, the real point of leisure was not an escape from work, but the preparation for political life in the public arena. A person who remained within the walls of their private life was regarded pitifully as ‘idiosyncratic’. The word idiot comes from a person who is incapable of public engagement.

My daughter has just completed her first year at Melbourne University and our relationship has taken an interesting turn. During the final year of her high school, I noticed that she had focussed on subjects that were procedural rather than interpretative. She had an incredible facility to memorize pathways and store facts. Whenever I tried to offer help, she became grumpy and impatient. I would talk and her eyes rolled, signalling that my thoughts were heading off on tangents and taking on a useless elongated form. I felt like a spindly TV antenna attached to a no longer functioning chimney.

Now that she is at university, we have big conversations about power and social divisions. She asks about Michel Foucault, and we dissect neoliberalism. Suddenly I am back as a wiki page on an open-source platform. She even admitted that: “my friends are complaining that I am giving long answers to simple questions, I am becoming a bit too much like you”.

She had worked out that at high school education was transactional. It was all about what you need to know, it was content that mattered. At university content is never enough.

Ask the questions

Education begins in asking the question why, and learning is about how you learn to follow those blind leads. Of course, there is a lot of new information to be gathered at university, but what should be gained is the capacity to compare, critique and create. These skills will always be useful for the rest of your life.

Finally, I want to end this letter to future students with an anecdote that illustrates another vital quality for public life. Sir Nicholas Winton was a London stockbroker who lived to the ripe age of 106.

He was also eventually credited with rescuing 669 Jewish children from the hands of the Gestapo. His enormous humanitarian efforts were dutifully recorded in a scrapbook but hidden in his attic.

Eventually his wife discovered the notes and a year before he died, at ceremony in Prague, he was asked why he kept it a secret. With sincere honesty and stoic humility, he replied: “I didn’t really keep it a secret, I just didn’t talk about it.”

Prof. Nikos Papastergiadis is the Director of the Research Unit in Public Cultures, based at The University of Melbourne. He is a Professor in the School of Culture and Communication at The University of Melbourne.