Christos Tsiolkas’s latest novel The In Between (2023) is a tender story of love and belonging. It begins with the story of a man who has suffered a brutal end to a relationship.

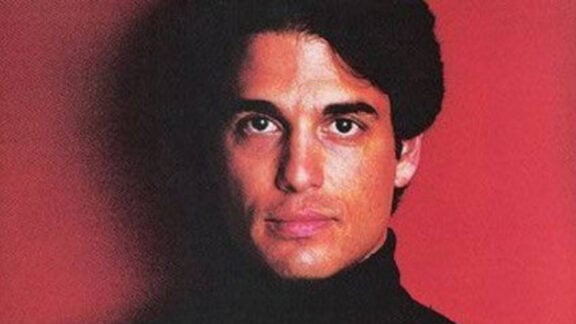

Perikles was trapped by love and anxiety. He was in love with a French man, but also caught in the shadows of Gerrard’s double life.

The love was more in an imaginary future than it was in the real present. After Gerrard clinically terminated the relationship with “carefully rehearsed words” Perikles plunged into an emasculating misery. “He wanted pure annihilation.” He woke up each morning with the sweat of night horrors and the taste of bile in his mouth. To master his grief, he returned to Australia and goes online to meet Ivan.

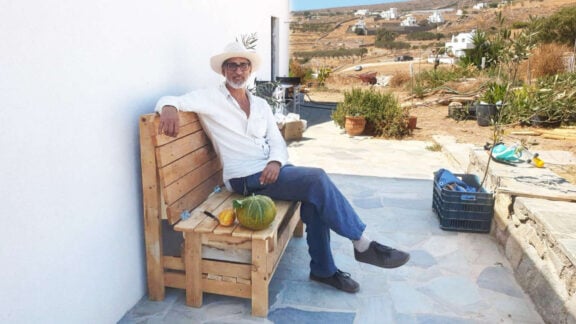

Ivan is burly, good with his hands, and a gardener. He has a razor-sharp bullshit detector. He knows how to read a room and hunt for sex on screens.

His focus is brusque and once satisfied he can flip and expunge the moment. But he too has been hurt and disgusted by Joe – a fickle lover. He would prefer to live a life that is marked by sincerity towards others and honesty over his own flaws.

Indirectly, the book is about politics. Near the mid-point of the novel Tsiolkas stages a dinner party. The air is thick with academic achievement, high levels of cultural literacy, and the imaginary superiority of the lower middle class.

The ethnic cookware, organic produce, and the occasional display of foreign phrases ensures that there is a sufficient waft of cosmopolitanism to mask the host’s pretence of authenticity and cover their shallow care for the guests.

The most urgent message that the meal is meant to convey is that this circle of friends is in but not part of the “racist shithole” called Australia.

Perikles is a translator who has learnt to flow amongst scholars and artists. The romance of Europe has singed his heart, but he is not a cynic. Ivan is more sceptical. He surveys the dinner party like a central defender on a football pitch. He is careful with each word.

He knows that if one step out of place then the game is lost. However, Ivan can also speak from calloused experience. He has the maturity to hold together contending forces. “Of course gay men are sexist.” He knows that minorities have their biases.

Flaws are part of human struggle, and admitting them is difficult, but it should not be fatal. Through Ivan’s laconic grit Tsiolkas debunks the self-righteous intolerance of the woked up left.

He strips back the new discourse of respect, the need to feel safe, and the aversion of touching each other’s bodies, back to its Calvinist and puritanical roots.

He strips back the new discourse of respect, the need to feel safe, and the aversion of touching each other’s bodies, back to its Calvinist and puritanical roots.

The more the left has become obsessed with micro-managing symbolic capital the smaller is its grip on the public imaginary. Tsiolkas exposes the petty-minded virtue signallers as ‘citizens’ who are only comfortable floating in their own dinner parties.

There needs to be more for Perikles and Ivan. Their attraction deepens into a bond.

But what kind of bond can be formed after they have been scorched by their previous partners?

Do you fall into the abyss, or leap into the arms of another lover?

Does the decoupling and lovesickness create a black hole, a dying star in the void, or is there another self-generating force that lunges you into another flame? What they find in each other is neither compensation nor supplementarity.

Before we return to these options, let’s do the maths.

The Ancient Greeks got on fine without the number zero. In Babylon they had a zero-like symbol that functioned a place holder. It was only the 7th CE that an Indian mathematician assigned zero as a number with null value.

Nature abhors a void. Maybe it wasn’t that the Greeks could not conceive of the idea of zero, but rather they were reticent. Of course, it was useful to have the number, but articulating it would be rather abhorrent.

Greek cosmology was primarily about the triumph of cosmos-order over chaos-zero. The battle scenes in the friezes from both the Parthenon in Athens and the Temple of Pergamon are about the total war with the Titans of chaos. It was an all-in battle. Hercules even summoned Eros to overcome a marauding giant. Had the other side won, it would have all gone the way of nothing, null, zilch, zero.

Greek philosophers were obsessed with how something could come out of nothing. They were brilliant observers of nature. Even things that could not be seen directly could be deduced by their form and traces. They noticed that the ship’s mast was visible on the horizon before the prow and saw that the shadow cast by the earth on the moon was spherical, therefore it could not be flat.

They measured the difference in the angle of shadows between two cities, and from this they could extrapolate to calculate the earth’s circumference. Given that no one has felt the rotation and orbit of the earth, they were convinced that the sun revolved around it. They also noted that gravity made everything fall toward us, and, quite plausibly, concluded that we must be the centre of the universe. It took two millennia for scientists to see past this worldview.

There is something deeply consistent between Greek mytho-poetic cosmology and the rational-philosophical science. Both were expressions of anthropocentric thought. Everything in nature was grasped through the prism of the sensory body. The Gods on My Olympus looked Greek.

Just as the ones in Africa were darker, and the ones in the North even had red hair. The Christian divide between the corporeal and the spiritual, or the subsequent Cartesian split between mind and body was never so severe and always more porous in the Greek mindset. Companionship with others, nature and the cosmos were the critical virtue to life.

The idea that we can find sufficiency in the self was anathema. Plato produced the most enduring image of lovers – two souls split in half and not finding completion until they bond once again. Aristotle went so far as to claim that the number two must precede one. It would be absurd to state: I think therefore I am. The purpose of thinking was to examine my existence in relation to you.

At a book launch in London Irit Rogoff asked me about the writer’s need for solitude. I responded:

“Much more important is the role of the other. I cannot begin thinking if I am not in a conversation.”

Freud was right, when two people make love, there are at least four people in the room.

So, how do we link eros to the primacy of the number two? Aristotle argued that every entity was not confined to the substances present in it; it also presupposed its opposite. Therefore, the number one could not exist without two. Patrick White could see this. His fictional memoirs were called The Many in One. Everyone was at least a dividual and a singular unit is not a fully formed entity.

For Aristotle one only made sense as half of two. One was potential for two. When two lovers meet don’t, they also feel that they are being reunited with their missing half? All those love songs about destiny are variations on this mathematical principle. Tsiolkas begin The in Between with an epigram drawn from Patrick White’s The Tree of Man.

“Two people do not lose themselves at the identical moment, or else they might find each other, and be saved. It is not as simple as that.”

A curious new space opened when Perikles and Ivan commit to each other. Their bond is not the fleshing out Plato’s image of the missing halves that are re-united. As their intimacy and trust deepens a new kind of respect is nurtured and it also cultivates sharper sense of the vast contingencies in the world. Perikles learns to refrain from imposing his erudition and appreciate Ivan’s acute observations.

Walking home from the dinner party they pass a group of women. It is a moment of existential contingency. The narrator briefly follows one of the women. She wakes up with a pounding hangover the next morning. With coffee in hand, she steps out onto her balcony, and peers aimlessly across the road. A burly man is entering a church. Ivan has sought repentance from a seething sense of guilt. The woman remains oblivious to the scene she is seeing, but the reader cannot fail to appreciate that the narrator has found a way to convey the significance of the hazy flaws of one man in the vast cosmos.

The novel reaches its crescendo in the poignant encounter between Perikles and Gerrard’s daughter. They have come together to disperse his ashes. Ivan’s radar is once again impeccable. He sees how by holding back at the funeral allows Perikles the room to forge a relationship.

In the dyad that has been formed by Perikles and Ivan there is more than the symmetry of complementarity. There is a decorous and wondrous in between space. Individuality, said the gardener to the translator, is the doubleness of the dividual.

Love, as we noted before, has three words in Greek: eros, agape and philia. By the end of novel, we see that philia, as care for the other, is a state that allows love to grow across the in between. It takes a long time to ripen. The final scene shows an elderly couple – Daphne and Thimio – struggling to grip the handrails of the Athens metro.

As they walk onto the busy street Daphne “deliberately slows down her pace, so that her husband won’t be humiliated by trying to keep up … Then there is the merging, disappearing and the belonging in the night.”