Fifty-one years after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, the wound of division remains open. For some, it’s a lived trauma; for others, fragmented memories of childhood summers cut short. And for the younger generations, it is an inherited nostalgia—passed down through words, photographs, and silences.

We spoke with three women of the same family—a grandmother, daughter, and granddaughter—who share not only a name but a collective memory. From Gypsou in Ammochostos to Melbourne, their stories weave a common thread of remembrance, dignity, and love for Cyprus.

Miranda Artemiou: “We fled with nothing but our souls.”

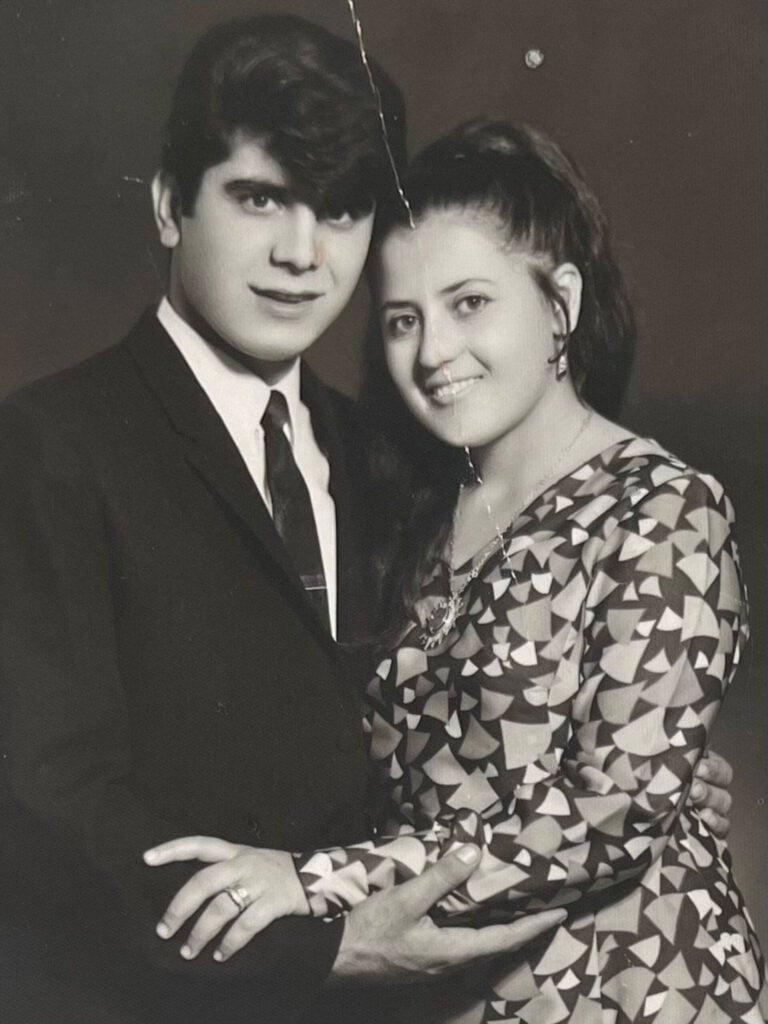

My name is Miranda Artemiou. I was born in Gypsou, a village in the Famagusta district. I married Artemios Artemiou from Milia in 1970, and four years later, in July 1974, the invasion changed everything.

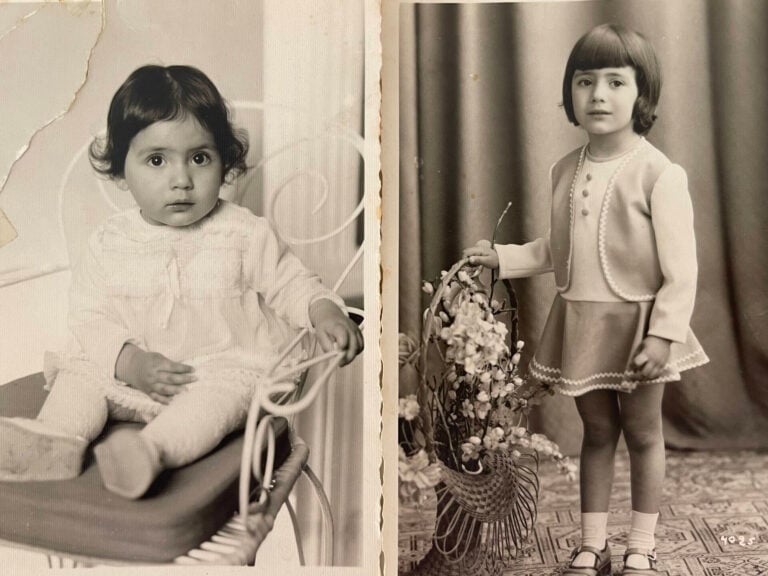

We fled in the first days. My mother, my two little girls—Isavella, three years old, and Demetra, six months, still unbaptised—and I. We left with nothing. No clothes, no nappies, no milk. Just our souls, trying to escape the bombings. We saw the bombs fall with our own eyes.

My husband and brother were on the front line, called as reservists. Both were new fathers with unbaptised babies in their arms. My brother’s father-in-law saved us—he took us to the British bases. That was the last time we ever saw our village.

Our lives changed overnight. Everyone was on the road, terrified, escaping in whatever way they could—cars, tractors, anything. We ended up in Ormidia, hosted by humble families who gave from their own meagre share. We will never forget the house that belonged to the late Misos, who gave us shelter that summer.

My father, Dimitris Neofytou—the village miller—was trapped behind. He had ten electric mills and fed the surrounding villages. Under Turkish guard, he kept the mill running, helping his neighbours bake bread and feed livestock. He was tortured but saved many young men who stayed behind, because he spoke fluent Turkish and warned them to avoid political talk. He returned to us only after the exchange at Ledra Palace. His sacrifice was never formally recognised.

We stayed in Cyprus for two years, living in abandoned Turkish Cypriot houses in Limassol—old homes with no comforts, but at least they had roofs for the children. My husband went to the UK to earn the money for our fares, and in 1976, we arrived in Melbourne.

We started from scratch. No family here—just a distant cousin of my mother who hosted us briefly. I worked during the day, my husband at night. We paid off two loans to buy our small house. Later, we brought my parents over. With their help, in 1981, I gave birth to our “Australian” child—our Savvas. It was beautiful for the children to grow up with their grandparents.

Despite our efforts, my in-laws couldn’t adjust to life in Australia and stayed in Cyprus, in refugee housing. So we returned every year, to ensure they wouldn’t be deprived of their son, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

When I think of Cyprus, I ache. We left behind our lives, our roots, my father’s mill, the land that raised us. And although we built a new life here, the old one is never forgotten. The wound never closed.

Isavella Djirkalli: “I was born into a world already wounded.”

I was three years old when Cyprus was forcefully occupied. I vividly remember a row of white refugee tents—a symbol of war and peace, safety and vulnerability. The feeling of being displaced is deeply rooted in me; it’s part of who I am.

The word “homeland” for me is both a place and an internal experience. It’s my identity. I have a birthplace and a homeland. It’s like having two heartbeats—a bond that sustains my soul. I’m proud to have been born in Cyprus and grateful to call Australia home.

My parents and grandparents always spoke of the invasion with deep sorrow—but also with sweet memories and tender nostalgia for what was lost. I don’t remember the threat itself, but I carry the trauma and fear through their words. The war lives in me as an inherited sense of grief, an emotion that can’t be easily explained.

As I grew older, I felt a duty to preserve the memory of my parents and grandparents—my heroes. I hold a deep love for Cyprus and Hellenism. I am grateful for the hope and opportunity that came from their decision to migrate. The branches of both lands are woven within me like a laurel wreath—symbolic of spiritual triumph.

The trauma and injustice of war are always there, like a shadow in the background. But as those wounds heal, my cultural identity burns brighter. For me, that is survival—it is my defence.

Artemis Djirkalli: “I carry a memory I never lived.”

My family comes from Famagusta—a city we can no longer return to. In 1974, during the Turkish invasion, my great-grandparents, grandparents, my mother Isavella (who was three), and my aunt Demetra (six months old) were forced to flee overnight, carrying only what they could hold.

One story that has never left me is how my mother and great-grandmother Chrystalla buried gold coins in the soil, hoping to come back for them one day. That day never came.

The few photographs that survived were sent to relatives in the UK before the invasion. They later returned them to us, and today those images are among the only tangible remnants of a life that vanished.

Carrying a memory I didn’t live feels like inherited grief. Trauma that lives in your body, even though you never witnessed the events. There’s no closure—just stories of a once-simple village life, and the photos that survived. I often wonder how my life might have been different if the war had never happened—if my family had never been displaced.

Growing up Greek Cypriot in Australia means living in two worlds. I had the safety and opportunity of Australia, but I also inherited a longing for a homeland I’ve never known—a homeland that was taken from us.

This legacy has instilled a deep appreciation for our culture, dialect, traditions, and food. My identity is multi-layered. I belong to a Hellenic diaspora that keeps Cyprus alive through everyday rituals—through the way we cook, speak, and remember.

For our family, “return” is not just a dream—it’s something we lived, though not as we once hoped. Four generations—my great-grandmother, grandparents, parents, and I—stood together in Gypsou and Milia, the villages they were forced to abandon.

We walked the streets they once called home, stood outside the houses that are no longer ours, and heard their stories in the places they began.

For us, return was an act of remembrance. It bridged the past and the present, offering connection to a history I didn’t live, but that lives in me.

Memory is not divided

Fifty-one years after the invasion, Cyprus remains divided. But in the hearts of these three women, the island remains whole—with its wounds, its villages, and its people—those who left, those who stayed, and those born into absence.

From Miranda, who fled “with nothing but her soul,” to Isavella, who grew up “in a world already wounded,” and Artemis, who “carries a memory she never lived,” we are reminded that memory does not have to be personal to be alive.

Each generation finds its own way to remember, to honour, to love. And as long as someone continues to speak the truth, to name the villages, to return—if only with their gaze—then return is more than a symbol. It is a way of life.

Because in the end, a homeland is never lost—so long as it is not forgotten.