Across continents and millennia, human cultures have turned to storytelling as a means of making sense of the world, of transmitting knowledge, and of affirming the bonds between people, land, and the divine. Though separated by geography and history, the ancient oral traditions of Greek mythology and epic poetry and the storytelling traditions of Indigenous Australia reveal striking parallels in their functions, structures, and underlying philosophies.

In both traditions, storytelling served as a vessel for cultural memory. For the ancient Greeks, the epic poetry of Homer was not simply entertainment; it preserved genealogies, explained natural phenomena, codified social values, and offered explanations for the origins of cities, peoples, and customs. Similarly, in Indigenous Australian cultures, stories — often called Dreaming stories — carry the weight of ancestral law, shaping understandings of geography, kinship, and moral conduct. These stories are not fixed myths of the past; they are living narratives tied to the present landscape and social fabric.

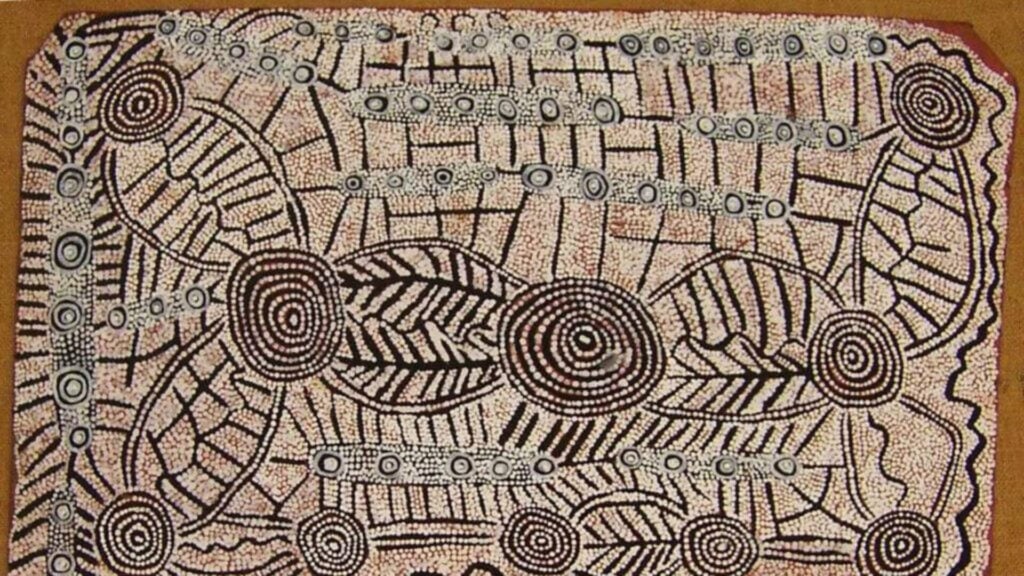

Another point of similarity lies in the integration of human, natural, and supernatural realms. Greek myths populated the world with gods who controlled the seas, the sky, and the earth, whose quarrels shaped human destiny. In Aboriginal storytelling, the land itself is alive with ancestral beings whose journeys and actions created rivers, mountains, and species. In both traditions, landscape and story are inseparable; knowledge of the world comes through knowing its stories.

The oral nature of these traditions is also significant. Before writing, knowledge in both cultures was transmitted through performance — song, recitation, and ritual. The aoidos of Greece, like the storytellers and songmen of Australia, held a respected role as custodians of knowledge. Their performances were acts of cultural preservation as well as artistic expression, reinforcing community identity across generations.

Finally, both traditions share an understanding that storytelling is not mere fiction. For the Greeks and for Indigenous Australians, these narratives spoke of truths deeper than historical fact — truths about humanity’s place in the cosmos, the patterns of nature, and the responsibilities owed to ancestors and descendants alike.

In an age of written texts and digital archives, these ancient storytelling traditions remind us that knowledge is often carried not in books, but in voices, in memory, and in shared acts of listening and retelling.

Sincerely,

Dr Panayiotis Loukopoulos