“Meet us at the beach car park opposite the Disinfection Bus stop”, said the Deputy Mayor of Kalamaria.

My cousin Panos knew exactly where to go; he winced when he heard the name. As we pulled up at the bus shelter, the word Apolimantirio was printed in bold and embedded in the typical blue frame.

Panos was shaken. “I have been coming to this beach all my life, but I never noticed the name.”

Feast, music, and memory

Forty years earlier, on my first visit to Greece, Panos and I had walked down to this spot. The foreshore was lined with tavernas. His sister Melina and her boyfriend had booked a table. As we entered, the waiters, dressed in black acrylic trousers and short-sleeved white shirts, carried six plates at a time along their left arms, and with their right hands, they held a single plate to help cut a path through the dancing crowds.

Our table was already filled with grilled mackerel and sea bass, anchovies and calamari, hand-cut potatoes, tzatziki and salads. There was twice as much food as we could eat. It was a time of bounty, we danced rembetika and drank tsipouro until dawn.

‘Welcome’ to Greece

Kalamaria is six kilometres to the East of the old city walls of Thessaloniki. It was a marshy land that was used for agriculture. None of the new apartment buildings are built on solid rock foundations. It was partially drained after the war. The sand, silt and clay dried.

Refugees from the Caucasus, Smyrna and Pontus built their homes meters from the port at which they disembarked. Their entry into Greece was via disinfection and quarantine stations. They were received with fear and contempt. The Caucasians were branded as “Bolsheviks” and the Pontians called “T0urkospiro” – or, Turk-seed.

Kalamaria is usually understood as a euphemism. It is a synthetic name composed of the two words ‘good’ and ‘part’. However, the ancient meaning referred to the side of the pier.

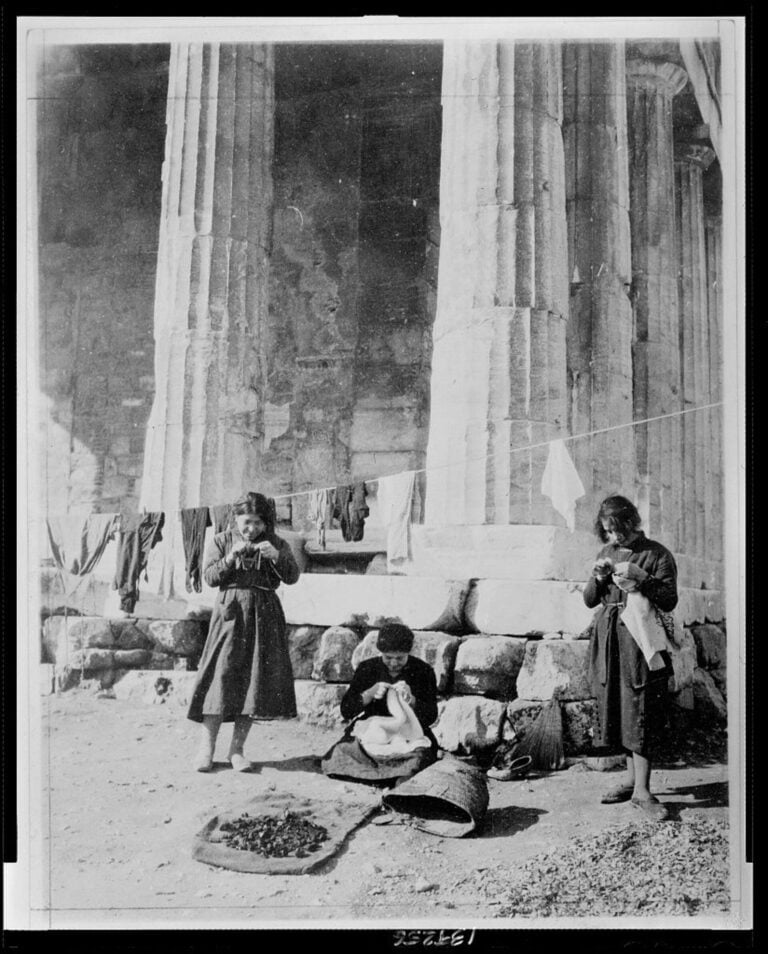

It was on this pier that Hariklia first set foot on Greek land. There were some abandoned British army barracks ahead. As Hariklia moved along the pier, she and her mother were separated from the men. They entered huts and were plunged into cold water and scrubbed with a green chemical soap. Their clothes, shoes and all their other belongings were dropped into boiling kilns. Everyone was shaved. The women felt humiliated, emerging with naked scalps. The few men who had money bribed the officials to bypass this trauma. Young and old, the women cried. Hariklia remained silent.

When their belongings were returned, the shoes were disfigured and the clothes were either shredded or shrunk.

Inside the old barracks, Hariklia’s father installed a blanket to provide a curtain of privacy. When it rained, the roof leaked, and there was no amount of wood to heat the room. Waste gathered outside, and malaria and dysentery ploughed through the waiting.

Kalamaria was now called the ‘cemetery’. Twenty to thirty people died each day. The dead were left to be licked by pigs before they were buried. Hariklia watched as her mother nursed an orphan. It was anything but the ‘good parts’. With the arrival of refugees in the 1920s, the population of Thessaloniki doubled.

Echoes of atrocity

After the Allied soldiers left in 1918, the Greek government repurposed their barracks into a Disinfection Centre. A vague remnant of it is still visible on Aretsou beach. My cousin Pano had swum there all through his childhood, and his parents relaxed on the sunbeds. Panos’s grandfather and my grandmother Hariklia, stayed in these camps for almost a year.

It was to this disinfection centre that the Nazis marched the Jews of Thessaloniki. Here doctors, entrepreneurs, and stevedores – hamals – had their heads gratuitously shaved and had their belongings robbed. In rags and under the searing sun, they were marched back to the centre. The Jewish hamals were so dominant in the port that it was closed every Shabbat.

The Jews had lived in Greece since the third century BCE, and in Thessaloniki their numbers grew after they were expelled by the Iberians – Spain and Portugal – in the Inquisition in the 15th Century. By 1940, forty per cent of Thessaloniki was Jewish.

When they were deported to the death camps, their friends and neighbours were bewildered. However, one Greek sighed: “At last, Thessaloniki will take a breath”.

What if?

I do not have a photograph of Hariklia from the time she arrived in Kalamaria in 1923. I have one of her two twins, Giorgos and Telemachus, who were sent to an orphanage during the civil war. Lazaros, her husband, had been shot by a sniper. It was a random execution. Lazaros was dancing at a baptism. The boys at the orphanage were standing before a brick wall. Barefoot on the mud, a loose smock covering their distended bellies. The most prominent features were their protruding knees and piercing eyes. Their heads were shaven. Everything is grey in this photo.

Hariklia survived the harrowing journey from Trabzon to Kalamaria. She never left the hem of her father’s coat and barely said a word. For the rest of her life, she would remain a stoic observer and practically mute.

At the beach now, which was once a disinfection station, pensioners in blue Speedos and brown one-piece swimsuits ambled between the coarse sand and the high modernist awnings. In the 1960s, this was the place to be.

The tavernas had crumbled and closed. There was not even a beach bar adorned in cane and palm fronds serving frappe coffee with ham and cheese toasties. Now there was an indeterminate status in the air. The deputy mayor is a pharmacist by training. Like the great author Primo Levi, he was also a chemist; his gaze is tender and full of longing, but his commitment to history is tenacious. He explained the significance of the photos that were on display, and then we stood on the invisible foundations of the huts and kilns. He kept saying: “What if?”.

*Professor Nikos Papastergiadis, is a cultural historian and author of many books; his most recent one, John Berger and Me, won the 2025 Michael Crouch Award for biography.