The debut feature by Greek Australian filmmaker Antonis Tsonis, Brando with a Glass Eye, is an exploration of art, emotional truth, or the paths we take -and the price we pay- in pursuit of our dreams.

Born in Athens and raised in Australia, Tsonis returned to his birthplace to tell the story of an artist’s struggle against socioeconomic barriers, the impact of consequences, and the inner battles of a fractured psyche.

In doing so, he captures a reality familiar to many immigrants.

Success depends not only on hard work and talent but also on timing, circumstances, the cultural, geographic, even physical obstacles one must overcome.

“It’s not a polite film, and yet it’s not irreverent,” Tsonis tells Neos Kosmos.

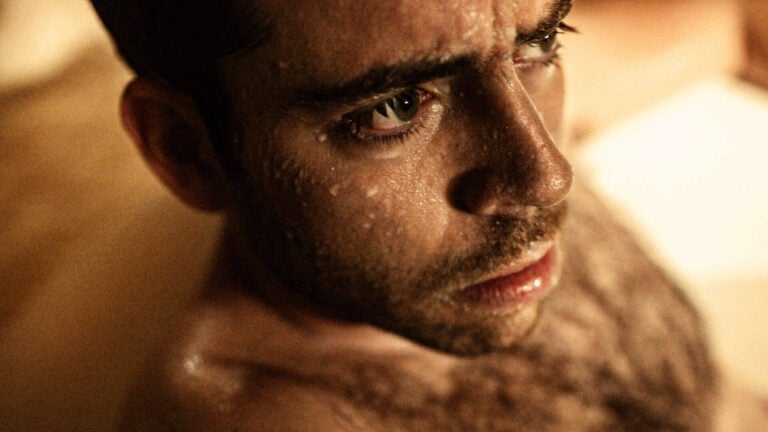

Through emotional realism and fluid cinematography, Brando with a Glass Eye, invites audiences into a world where art and life collide.

Athen’s gritty beauty

Tsonis was 11 months old when his family left Athens and moved to Australia.

“Brando with a Glass Eye” was a “deeply personal, cinematic, and experimental” project, one rooted in Athen’s gritty landscape.

Shot in Athens, with dialogue in Greek, the film rejects the postcard version of Greece’s capital often seen in magazines and social media.

“In all that grit and decay, there’s a certain beauty,” Tsonis notes.

“Fate took us there,” he says.

Fate, or an instinctive pull toward the place he was born?

Drawing on “ingrained memories” from “prolonged trips” to Athens at ages 11 and 12, Tsonis sought to capture the city’s rough, lived-in texture

“There was an aesthetic that never left me … it was imprinted in me.”

Athens is not just a backdrop— it’s a character within the film. A city where cracked sidewalks, protest-marked walls, tangled wires, and aged balconies tell their own story.

“I feel connected to that. And I think there’s a certain longing and pain in all of those aesthetics. But that’s where the true beauty resides.”

Beyond Tsonis’s “deep love for Athens,” other factors influenced his decision to film there.

After shooting his short film 3000 (2016) in the Athens, he “fell in love” with the local crew and the on-location experience.

The support he received from Athen’s film industry and funding bodies confirmed his choice to shoot the film in his birthplace.

“The Greeks were ready to do that and that was a big thing for me, getting the right support around me for that kind of a risky film.”

Art’s double-edged power

Brando with a Glass Eye follows Luca, an aspiring actor from a disadvantaged socio-economic background in Athens. When offered a chance to study method acting in New York, he sees a way out but is drawn to choices that could cost him everything.

Driven by that urge, Luca and his brother commit a robbery—an “evil act” that triggers series of life-altering consequences. The film touches on themes of self-deconstruction, the challenge of “constructing the soul,” and the isolation of that journey.

These ideas live in Yiannis Niarros’s complex portrayal of Luca.

His performance serves as a love letter to method acting— where actors fully immerse themselves in the emotions and motivations of their characters to deliver raw, authentic work.

Tsonis reflects on the dual nature of art and method acting—the way it can heal or harm.

“Method acting and art can be something that saves a life—or be something that leads to destruction.”

Entry barriers

Marlon Brando was seen as “America’s intellectual pin-up boy” Tsonis says. He was a mix of talent and beauty – who became one of the 20th century’s most influential actors.

But, would he have “made it” if he had a glass eye?

Or even a less evident barrier, like being from a lower socioeconomic background in Greece?

Brando with a Glass Eye reveals Luca’s struggle to survive, as an artist, in an environment that lacks support. Entry barriers, whether physical, social, or cultural, shape access to opportunity.

This is embedded in the collective consciousness of many migrants and immigrants who left their homeland seeking a better life the filmmaker says.

For many immigrant Greek Australians success wasn’t just about hard work.

It’s also about being in the right place at the right time, or seizing opportunities unavailable back home.

As a second-generation Greek, Tsonis may not have experienced the challenges of immigrant life firsthand, but his father, a “very successful salesman” turned publisher, did.

“He would go to door to door selling encyclopedias, and I remember he built himself up from nothing,” Tsonis says.

The lived experience of struggle and resilience, themes in the post-war Italian neorealist film movement influenced Tsonis’s creative decisions in Brando with a Glass Eye.

A humbling experience

There is something inspiring about actors who are willing to go to great lengths to pursue their dreams. A theme central in Brando with a Glass Eye.

“My love for film and acting got me to do this one,” he says.

For him, making his artistic debut felt “dangerous,” much like diving.

“You can do a straight simple dive, or you can do the really complex risky dives,” he says.

Art “embedded in emotional realism” is at the heart of Tsonis’s process.

“I’m writing reality in terms of something being emotionally true to me.”

He adds that the key lessons and values, learned from making Brando with a Glass Eye, were “really humbling.”

“It’s helped me invent myself in the way that I saw myself … And you feel you can do more and better. It’s a drive.”

Tsonis is now working on a new project.

Unlike his working on short films, his writing process for this feature is more “fluid and painterly”.

“I keep shaping scenes and putting down dialogue and it naturally evolves.”

Making international waves

Brando with a Glass Eye is a “strange” film—in form and in its unexpected trajectory through festivals and acclaim, says Tsonis.

Produced by Tia Spanos Tsonis (Antonis’s wife) and Blake Northfield, with Peter Kallos among the executive producers, the film has become a favourite at international festivals.

At the Athens International Film Festival, it was programmed by the Artistic Director and film critic, Lukas Katsikas, known for rarely choosing Greek features.

Katsikas said it was the “biggest surprise of Greek cinema in recent times.”

Thessaloniki International Film Festival, which typically excludes widely screened Greek films from competition, made an exception—creating a new category to include the film.

After its world premiere at Slamdance—where made history and became the first Greek-language film in the Narrative Features competition—it was showcased at over 25 international film festivals.

These included screenings in Athens, Thessaloniki, Sofia, Ferrara, Berlin, and London, where it won Best Film at the New Renaissance Film Festival.

From international and local acclaim, Tsonis acknowledges the emotional risks of creating such a personal film, navigating a spectrum of reactions.

“I think audiences also give the energy to the film,” he says.

Reflections through art

The film had its Australian debut at Lido Cinemas in Melbourne in June.

Notable attendees included politicians such as Ministers Steve Dimopoulos, and Nick Staikos.

Antonis Tsonis and Peter Kallos also took part in a Q&A session, sharing insights about the film with the audience.

Brando with a Glass Eye is showing in select cinemas across Australia. It has also secured an international distribution deal for a worldwide release.

The film’s positive critical reception also reflects a surging interest in Greek stories told through unconventional perspectives.

It’s a powerful reminder that between the conscious and subconscious, art holds up a mirror, not just to the world around us, but to the deeper truths within us.