Few arguments in political economy are as perennial as the dispute over what is best for modern society – socialism or capitalism. The question is as old as the birth of the Spinning Jenny, which launched industrialisation in 1764.

Trying to make capitalism more equal and more stable has been at the core of what to do with how to better distribute surplus value, that value produced by a worker, which is, in effect, the capitalist’s profit. The question is alive today as it was three centuries ago – is capitalism in perpetual crisis, ready to topple over into war and bloody revolution? As its critics would have it – from Marx to Varoufakis? Or is capitalism, as its defenders argue, the only system capable of delivering prosperity, innovation, and freedom in the most equitable possible way?

Recently, the debate was brought into sharp focus in New York, where Richard Wolff, an advocate of socialism, and Gene Epstein, a defender of capitalism, crossed swords over whether socialism is preferable to capitalism as an economic system that promotes freedom, equality, and prosperity.

Wolff, a Marxist economist and author, pressed the case that capitalism breeds crises, entrenches inequality, and hollows out democracy by concentrating power in employers at the expense of employees. Epstein, a free-market libertarian and former economics editor at Barron’s, responded that despite its flaws and distortions, capitalism is far superior to socialism because it delivers choice, fosters innovation, does so efficiently, and respects individual liberty.

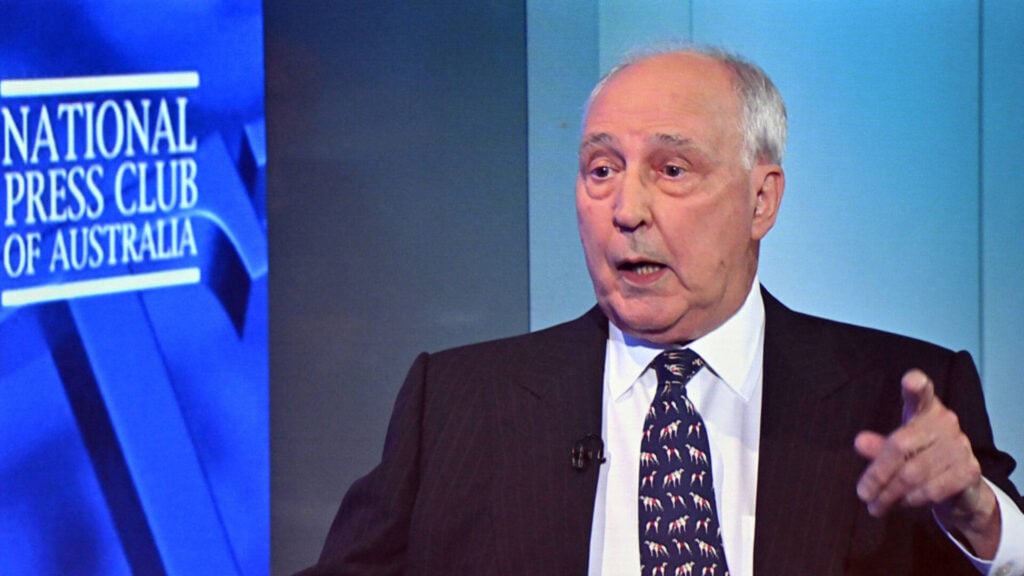

The debate was often theatrical and at times, caustic. Nevertheless, for me, it raised a question worth posing from an Australian perspective: What would Paul Keating, our former Prime Minister—the “Placido Domingo of economics”—have done?

Keating was no ivory-tower theorist. He was a reformer, a showman, and above all, a pragmatist who dragged Australia into the modern economic era with bold reforms. His approach to capitalism and socialism was neither doctrinaire nor sentimental. He treated economics like opera: dramatic, disciplined, and capable of soaring heights when conducted well.

The debate was often theatrical and at times, caustic. Nevertheless, for me, it raised a question worth posing from an Australian perspective: What would Paul Keating, our former Prime Minister—the “Placido Domingo of economics”—have done?

This piece considers Wolff’s critique, Epstein’s defence, and Keating’s likely response. It argues that Keating would have cut through the abstractions with characteristic flair, insisting that capitalism must be tamed, civilised, and orchestrated—not abolished, not worshipped, but conducted like a symphony.

A Socialist critique of capitalism: Instability and inequality

Richard Wolff’s position rests on three enduring criticisms of capitalism: instability, inequality, and a lack of democracy.

Capitalism, Wolff contends, is inherently unstable. Every four to seven years, advanced economies experience recessions or depressions not caused by natural disasters or war but by capitalism’s own internal contradictions. Millions lose their jobs, homes, and livelihoods in crises that are “baked into the system.” To live under capitalism, he argues, is to live under permanent threat of economic collapse.

Wolff also stresses the stark inequality produced by capitalism. A handful of billionaires, he notes, control more wealth than billions of ordinary people. To him, this is not an accidental side effect but the logical result of a system that funnels profits upward while wages stagnate. Such disparities, he argues, undermine social cohesion and perpetuate privilege.

Undemocratic structures

Finally, Wolff views capitalism as fundamentally undemocratic. Political democracy may have abolished kings and queens, but the workplace remains a feudal structure. Employers—the “little kings”—make decisions about what is produced, how it is produced, and what happens to profits, while employees have little say despite creating the value. Wolff’s solution is “economic democracy”: worker-owned and worker-run enterprises where decision-making is collective and profits are shared.

For Wolff, socialism is not about recreating the authoritarian Soviet Union but about extending democracy into the workplace, making co-operatives the norm rather than the exception. The roots of workers’ democracy can be found in medieval German guilds and are most evident in modern notions of ‘social democracy’, again in Germanic–Nordic nations.

The Capitalist defence: Freedom of choice

Gene Epstein, by contrast, insists capitalism, despite its flaws, remains the best system humanity has devised. Epstein’s central argument is that capitalism offers freedom. Workers can start their own businesses, join co-operatives, or sell their labour in traditional firms.

Nothing in capitalism forbids worker ownership—indeed, co-ops exist within capitalism. Workers’ and consumers’ cooperatives have existed since the 19th Century. The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, founded in 1844, established the principles—most notably the patronage dividend and the Rochdale Principles—that became the prototype of the modern co-operative. Afterglow coffee roasters and brewers, in Richmond, Virginia, US, is a worker-owned cooperative that runs on consensus, no hierarchies and is committed to fair wages. If workers rarely choose them, Epstein suggests, it is because most prefer the flexibility of conventional arrangements.

Prosperity and innovation

Capitalism, Epstein argues, fosters prosperity by encouraging innovation. From the steam engine to the smartphone, from heart transplants to semaglutide injections that have saved diabetics, capitalist competition and investment have driven major technological revolutions. Epstein warns that socialism, with central agencies allocating finance and labour, would stifle creativity and slow “creative destruction”—the process Joseph Schumpeter saw as vital to progress.

Equality through growth

Epstein does not deny capitalism produces inequality, but he insists it simultaneously lifts millions out of poverty. He points to China and India, where market reforms lifted hundreds of millions into the middle class. Global inequality, he argues, has narrowed because of capitalism, even as inequality within nations has grown.

For Epstein, the verdict is clear: socialism has produced repression and scarcity wherever tried, while capitalism, even in its flawed form, delivers growth, choice, and innovation.

Lessons from history

The historical record supports neither side in absolute terms. Socialists can point to Scandinavia, where social democracy has combined markets with robust welfare states to produce egalitarian outcomes. They can also cite successful co-operatives like Spain’s Mondragon, which thrive within capitalist systems.

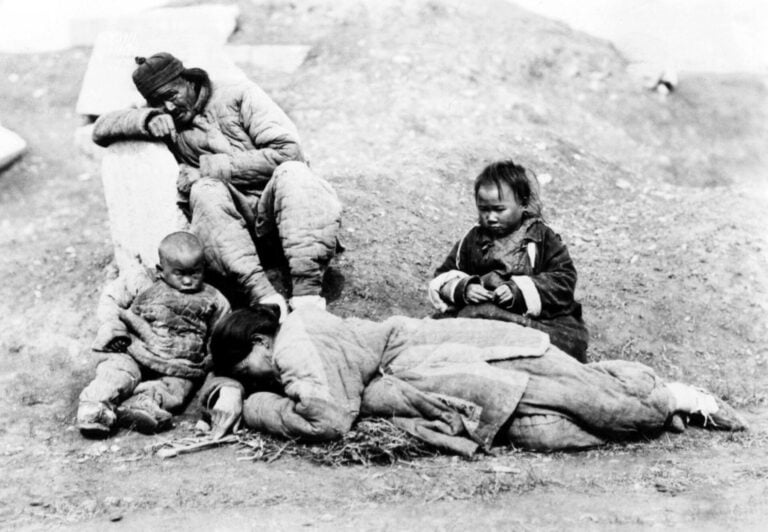

Capitalists, in turn, point to the failures of the Soviet Union’s or Maoist China’s central planning disasters. China’s Great Leap Forward, for example, brought on mass famine in an attempt to ramp up industrialisation.

Authoritarian, centrally planned socialism produced repression, poor distribution, and mass suffering—resulting in over 40 million deaths in the Soviet Union and Communist China during the 1940s and 1950s. By contrast, capitalism’s defenders highlight its achievements: rising global life expectancy, the reduction of extreme poverty, and major technological innovation. China’s shift toward capitalism from the 1980s onward is often cited as the clearest example of capitalism’s “miracle,” driving tremendous economic growth and greater prosperity.

Yet capitalism, too, is awash with blood: colonial exploitation, entrenched inequality, and two world wars born of imperial competition. Crises, from the 1929 Great Depression, the 1986 Crash, and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, reveal that unregulated markets impose catastrophic costs.

The truth is that both systems are capable of excess, failure, and renewal. Which brings us back to Keating.

Keating’s View of Capitalism

Paul Keating was not a socialist. He was a suburban boy, part of Australia’s working-class royalty, the beneficiary of post-war growth, union power and entrepreneurship. His career was defined by reforming, not dismantling, capitalism.

He floated the Australian dollar, deregulated financial markets, reduced tariffs, and created compulsory superannuation. These reforms dragged Australia into the global economy and helped secure long-term prosperity.

Yet Keating’s capitalism was never totally laissez-faire. He believed in fairness and redistribution, what Australians call the “fair go,” and recognised capitalism’s power to create wealth but also its tendency to concentrate it. His instinct was to “civilise” capitalism through institutions, rules, and redistribution.

Where Wolff wants to democratise the workplace, and Epstein insists capitalism already offers choice, Keating sought a third way: broaden participation in markets, spread ownership, and regulate excess. His reforms created what he called “a people’s capitalism,” where superannuation funds turned workers into investors and stakeholders in the system.

Keating’s prescription: Pragmatism and grandeur

On instability

Keating saw instability not as proof capitalism was broken but as evidence it required careful management. Famously describing the 1991 downturn as “the recession we had to have,” he treated crises as catalysts for reform. Unlike Wolff, he did not seek to abolish capitalism; unlike Epstein, he did not dismiss its flaws. He sought institutions—independent central banks, fiscal discipline—that could absorb shocks without destroying livelihoods.

On inequality

Keating recognised capitalism concentrates wealth, but his response was to broaden access. Compulsory superannuation gave millions of Australians a stake in capital markets. It was redistribution through ownership: spreading wealth not by dismantling capitalism but by ensuring workers had “skin in the game.”

On democracy

Wolff views workplaces as inherently undemocratic; Epstein, on the other hand, as free. Keating would have been blunter and may have said, “Australians don’t want to sit in committee meetings all day. They want jobs, security, and homes.”

For him, democracy was not about co-managing firms but about ensuring governments delivered prosperity and fairness.

Keating between Wolff and Epstein

Placed in that New York debate hall, Keating would have cut both sides down with characteristic flair.

To Wolff, the socialist, he might have said, “Mate, Australians aren’t itching to sit around in workplace soviets deciding how many widgets to knock out each week.

“They don’t want another layer of meetings—they want jobs, homes, and a stake in the future.

“You can run your co-ops, good luck to you, but don’t think that’s a model for the nation.”

To Epstein, the capitalist defender, he might have snapped, “Gene, you talk about markets as if they were the Garden of Eden. But here’s the truth: leave the market on its own, and it’ll eat its young. It’ll chew up workers, hollow out industries, and call it efficiency.

“A market without rules is like an orchestra without a conductor—just noise, no music. You need someone up front setting the tempo, otherwise the whole thing collapses.”

The fat lady sings in Keating’s Opera

Paul Keating would not have endorsed Richard Wolff’s proposition that socialism is preferable to capitalism. Nor would he have embraced Gene Epstein’s libertarian optimism that capitalism needs only to be left alone. He would have insisted that both views are too narrow.

For Keating, economics was not about ideology but performance. Capitalism was the stage, socialism the chorus, and the state the conductor ensuring harmony.

And if he had been closing that New York debate, Keating might have finished like this, “Capitalism’s not an angelic choir, and socialism’s not Satan’s brew.

“They’re just tools—systems we bend to our will. The trick is to orchestrate them. You don’t let the violins drown out the brass, you don’t let the chorus run the whole show, and you don’t sack the conductor halfway through. You balance it, you bring it together, you make it sing. That’s how you get harmony, and that’s how you get prosperity with a fair go.”

That was Keating’s genius – not to choose capitalism or socialism, but to conduct both into a distinctly Australian symphony of prosperity and fairness.

*Tony Anamourlis is a tax law specialist in multinational transactions, negotiating with the Commissioner of Taxation and other regulators and is a regular contributor to Neos Kosmos.