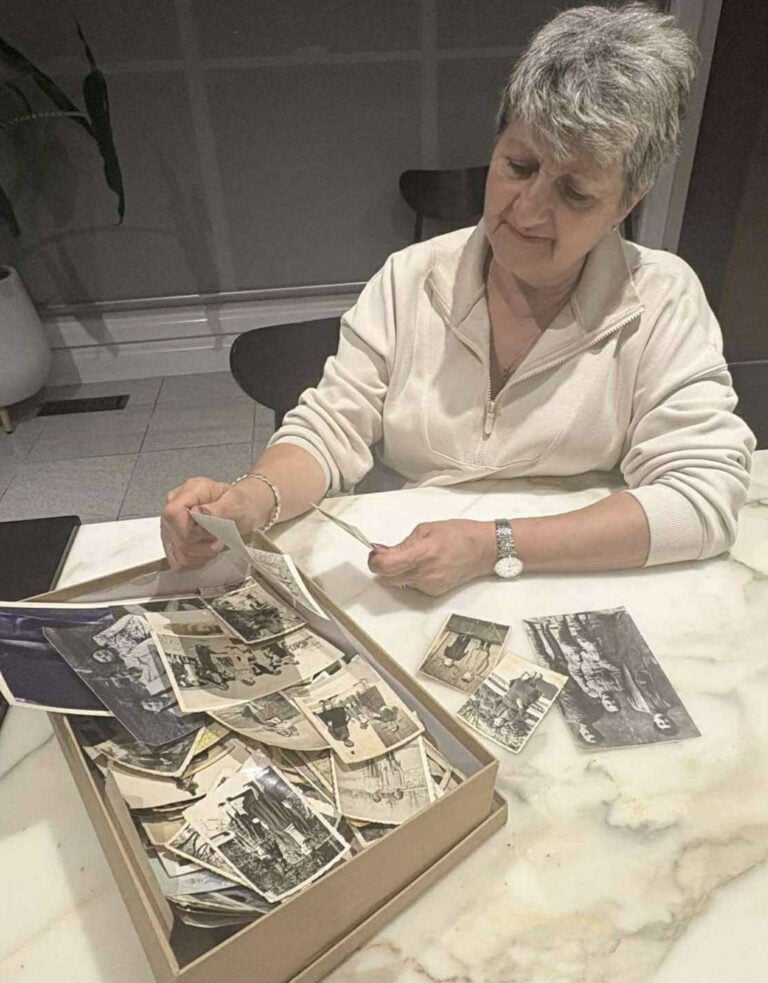

As we approach the anniversary of the unveiling of Ballarat’s George Treloar Memorial this coming October, I decided to discuss the significance of the Memorial with one of its key community organisers and champions – Litsa Athanasiadis, chair of the George Devine Treloar Memorial Committee.

As we chatted Litsa recounted her personal connection to the Asia Minor catastrophe and the Christian refugees who were forced to flee their homeland in the 1920s. It was this direct family experience which has driven her to work with many others to create the Memorial and to promote awareness of the refugee work of Australians like Major George Devine Treloar.

Anyone who has travelled to Ballarat’s Sturt Street to see the memorial to George Treloar will be fascinated to learn of the story of the young girl depicted in bronze seated next to George. The combination of these two figures is an essential part of the beautiful memorial created by famous sculptor Lis Johnson. Many who attend the annual service at the Memorial will be aware that the girl has been given the name Lemona by the Committee.

Litsa explained to me that the name Lemona was chosen because it resonates so powerfully with both the Pontian diaspora generally and personally with Litsa. As we sat in her Melbourne home, Litsa recounted her family story passed down to her by her own mother Varvara.

She began by telling me that Lemona was once a young girl from Trebizond on the Pontian coast, on the southern shores of the Black Sea. Barely a teenager she had enjoyed life with her sister Irini and the rest of the Kokinidis family in this great trading city. Her name was not originally Lemona but Anastasia but more of that later.

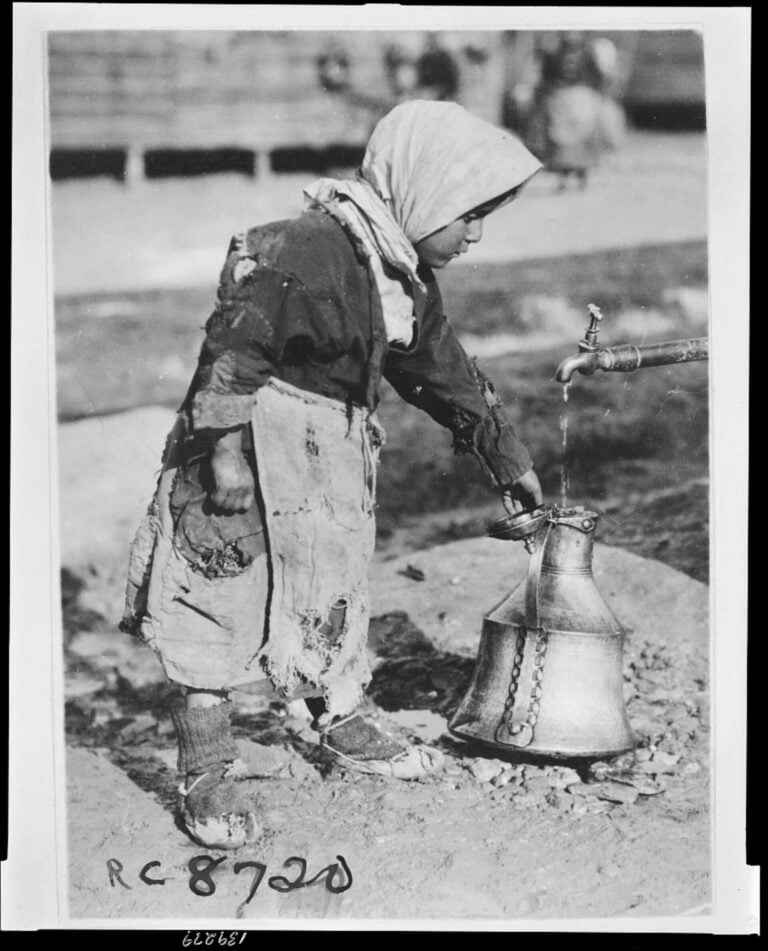

With the coming of the Asia Minor catastrophe to Pontus the family was forced to flee their homeland. As they boarded the boat that would take them to safety, the sisters were separated and the last that Irini saw of Anastasia was her falling overboard into the sea. Whether she fell by accident in rush to escape or was thrown there by their enemies, we don’t know. Only that this is the last time that Irini saw her sister as they fled.

Many years would pass. The troubles for Varvara and her mother Irini and father Nikolaos would last many years. Crossing the Black Sea, the family first settled on the southern coast of Soviet Russia, near Novorossiysk, a large port city with origins stretching back to a Greek colony named Bata in antiquity. In the late 1930’s Irini remembers that the men were separated from their families and exiled to Siberia. It was here that many died, including her father Nikolaos. As a result of this, the family of mother and five children somehow made the difficult journey from Soviet Russia to Greece. Arriving in Athens in 1939, the family made their way north settling in Agios Dimitrios near Kozani.

One can only imagine the life of these poor refugees. They had suffered expulsion from their Pontian homeland, the terrible experience of post-civil war Soviet Russia and then arrival in northern Greece, fatherless and about to face the Axis invasion and occupation.

It was during their time at Agios Dimitrios following the end of the war that a blind pedlar approached Irini at the door of the family home. He was known to the family and the village, travelling around the region selling his wares. This time he enquired if Irini had a sister known as Lemona. She said she didn’t. But the pedlar was insistent, there was a young woman living not far from there – just over 40 kilometres away at Grevena – who sounded like Irini. If Irini would write a letter of introduction the pedlar would deliver it. What did she have to lose Irini thought. The curious story brought the memory of her sister Anastasia to her mind. Could she have survived?

Irini wrote the letter and the pedlar was soon on his way. Days passed and soon a woman arrived at their door. Irini’s young daughter Varvara remembered vividly the scene many years later. Here was a strong, young woman that looked like her own mother. She had a similar physique and her hair was plaited in a way that was similar to her mum’s, a style familiar to those from Trebizond.

Soon her mother was at the door and the crying and emotion of recognition flowed. Irini never forget the emotion of the scene. This was long lost Anastasia. She had indeed survived being thrust into the waters of the Black Sea all those years ago. Somehow she had made her way to Greece in the 1920’s. Soon she was married, as a 13 year old girl and was living in Grevena. Her husband had lost his first wife and insisted that Anastasia take her name – Lemona. This is why Irini and her family had been unable to find her. Anastasia had become Lemona with her new married surname.

For all these tragedies, Anastasia – now Lemona – had survived the tragedy that befell Pontus and finally been reunited with her sister and her family. Her story was so powerful and evocative that Irini’s daughter would hold this memory for years, passing it on to her own daughter – Litsa.

The story of Lemona is only one of the hundreds of thousands that flow from the Asia Minor catastrophe. But in a way it is symbolic of both this tragedy and the regeneration that followed survival. All of those in Melbourne who supported the Treloar memorial have their own similar family stories. Lemona represents them all and she lives in the bronze sculpture beside her protector – Ballarat’s George Treloar.

In giving this name to the statue Litsa also explained that Lemona itself has a particular resonance for the Pontian community. For it is also the title of a famous traditional Pontian song. Melbourne Pontian musician and teacher Kostas Pataridis informed her that the name means literally “the sun’s mother”. The song forms a dialogue between Mother Earth and man, focusing on the need for man to respect the earth if he is to share in its abundance. What a beautiful response to the challenges facing the refugees of Pontus and an evocation of their own connection to their land.

It is the survival of personal stories and songs like these that drove the creation of the George Treloar Memorial. It is over ten years ago this year – in 2015 – that the fundraising began to create the Memorial in Ballarat. George Treloar’s assistance in the resettlement of over 100,000 Christian refugees from across Asia Minor connected to many in Melbourne’s diaspora whose heritage stretched all the way back to this human tragedy. Community discussions were held and meetings convened at Victoria’s Parliament House, Ballarat’s Town Hall and of course at Pontiaki Estia in Sydney Road Brunswick.

As a result of four years of hard work, the proposal to create the new Memorial had garnered significant community support across Victoria. Along with Merimna Pontian Kyrion of Oceania and the City of Ballarat, the George Treloar Memorial Committee received generous support from a wide range of community organisations and individuals. The former included the Central Pontian Association of Melbourne & Victoria ‘Pontiaki Estia’, the Panthracian Association of Melbourne, the Pancretan Association of Melbourne, the Central Union of Elassona & Districts ‘O Nikotsaras’ and The Greek Orthodox Community of Moreland. The latter included Rev. Fr. Antonios Amanatidis & Presvitera Despina, Sakis & Litsa Athanasiadis, Family of Elizabeth Treloar (M Jones), Sotirios & Anastasia Kalaidopoulos, Emmenuel & Marina Pattakos, David & Helen Treloar, Kostas & Vicky Tseprailidis and the Tsalikidis Family. All of these contributors are acknowledged both on the memorial itself and in the commemorative booklet issued at the unveiling.

Litsa says that the Memorial Committee has always felt strongly that those who supported the Memorial’s creation should be recognised.

“George Treloar helped tens of thousands of refugees, many of them relatives of those who made new lives in Australia. This is what moved these organisations and individuals to so generously support our commemorative project. We will never let their gift go unappreciated. The Memorial would not exist without them”, Litsa said.

The commitment to raise awareness of the refugee work of George Treloar led the Committee to financially support the George Devine Treloar Community Service Award at his old school, St Patrick’s College. Litsa and I have attended the impressive scholarship ceremony on a number of occasions. This support has been essential to the continuation of the award.

The Committee has held an annual memorial service in Ballarat at the memorial every year since its unveiling in September 2019. Students and teachers from St Patrick’s College take part in the service. This year’s service represents the tenth anniversary since fundraising began and six years since its unveiling. An achievement indeed.

This year’s service will take place on Sunday 12 October, commencing at 11am. The service will take place at the Memorial in Sturt Street, located near the intersection of Sturt and Errard Streets in central Ballarat. Following the service a lunch will be held at the Golden City Hotel, 427 Sturt Street, walking distance from the Memorial. All welcome.

Wreaths will not be necessary at this year’s service. The Committee has decided that instead anyone present who wishes to make such a personal part in the service will be able to lay special floral bouquet of Helichrysum flowers which grow in the Pontus region and have been chosen as a symbol to represent the Pontian genocide. These bouquets will be available at the service.

*Those wishing to attend should contact Penny Tsombanopoulos by 1 October 2025 – 0409 850 109 or merimna.ocea@gmail.com.

*Jim Claven OAM is a trained historian, freelance writer and published author. He has been secretary of the George Devine Treloar Memorial Committee since its creation. He can be contacted via email – jimclaven@tahoo.com.au