Nearly two decades after swapping Melbourne for the Aegean, Kosta Nikiforidis didn’t find the life he imagined, he engineered a better one. His “barren” Paros block now gives back more water than it uses, and his push to end what he calls a “Cycladic housing emergency” is challenging how the islands build, plant and survive.

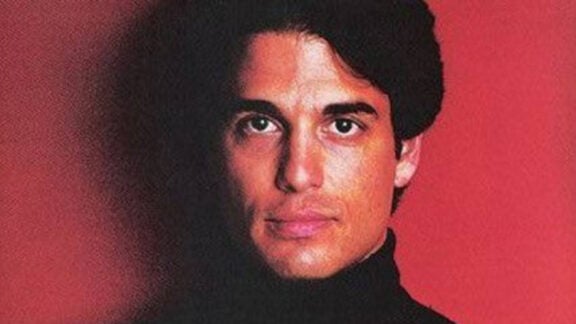

The son of migrants from Kythera, Nikiforidis, grew up in Australia.

Eighteen years ago – before the latest Greek migration wave to Australia had started – he and his wife, also a Greek Australian, decided to move to Greece with their two daughters.

“The kids were young, we had a business that was doing quite well, and so we thought ‘how about we go back to our roots, learn the language, earn some euros and travel?’,” Nikiforidis tells Neos Kosmos.

Things didn’t go as planned, he admits with a laugh.

“As it turns out, I’m having trouble learning the language, even though it’s my native, I haven’t been able to earn much money and we’re not travelling that much!

Spending the first years in Corfu, and then Rhodes, they eventually settled in Paros.

“Of all the islands, Paros has been certainly the best for us. We’ve found good friends, and we’re really happy here,” Nikiforidis says.

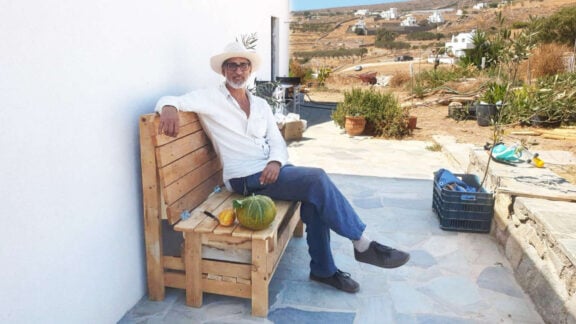

Paros is where Nikiforidis put his passion in sustainable living into practice.

And he hopes to inspire fellow islanders to reverse what he calls a ‘Cycladic housing emergency’.

“It’s time to rethink how we build. I want Cycladic housing to be part of the climate solution, not the problem.”

It all started when he bought a property on Paros to build their house.

“It was a forgotten plot, untouched for 70 years, just two trees and weeds.

“When my mum saw the property, it was just rock, barren. ‘She said, if you buy it, I’m cutting you off.'”

But Nikiforidis was determined to go ahead.

He wanted to apply his learnings from studying permaculture, a holistic design approach in land management, that originated in Australia in the 1970s and has inspired thousands worldwide since.

“There’s two things you need if you want to do passive solar housing and eco-sustainable design,” he says.

A plot setup that faces towards the sun, while facilitating water catchment from the land above it.

“And this property, as barren as it was, had both of those. It had the potential to catch water, and we had a southwest view.

“So, I was hooked on it. Nobody else could see the vision because it was just piles of rock, but we’ve been transforming that.”

Over the last four years, Nikiforidis has put systems in place to fertilise his land without relying on electricity.

Capturing every drop of winter rain that falls, his methods include using gravity to direct water in slopes, gathering stormwater in a large swale, and digging ditches, some even by hand, to maximise water absorption in his land and minimise run-offs.

The result?

“Not only am I fully water secure, but my land is also water positive,” he says.

Nikiforidis calculates that his water catchment methods cover his annual water consumption and put tonnes of water back into the island’s aquifer.

“I used 110 tonnes of water for my entire use last year. That’s my house, all of the families that visit, all of our shower, watering the gardens and my plants. And we normally get about 280 tonnes of water that we put back.”

This year was different due to the flash floods that hit Paros in April.

Nikiforidis says he managed to return to the ground double the usual amount of water, thanks to his large 150-metre-long swale capturing floodwater and slowly soaking it into ground over the following days.

“And that was my definitive point to say this is worth every cent you put into it. Because that one rain put back more than two and a half times my annual water use.”

Last July, almost all of Greece “displayed above-normal drought levels for this time of year” according to the National Observatory of Athens.

Nikiforidis believes the Cycladic islands used to have systems in place to combat droughts, but peoples’ know-how and interest have been lost.

“The ancients knew what they were doing. There are terraces everywhere on contour, but they’re all eroded and breaking down. So, they’re not capturing and soaking that water in.

“Then we have overtourism, so they’ve got bores and wells everywhere.”

The biggest environmental risk facing Paros at the moment, he adds, is drought.

“What’s happening is we are draining the aquifer faster than the island can replenish the water.

“Whereas this block of land, in one rain event put back more than twice the amount of water I use annually.”

Nikiforidis has been in contact with local professionals in the areas of construction and water supply to garner support.

He wants to push for legal changes that facilitate electricity-free solutions for making properties water-secure and water-positive.

“I want to focus on Cycladic housing and share a proven way to enhance both built and natural environments, that could help re-green the islands. ”

It’s a method he thinks could serve as a blueprint for houses, hotels and villas in the island complex.

“We can, and must, inspire governments to rethink the rules.”

Despite being Greek Australian and living in Greece for the last 18 years, Nikiforidis says his intention to help often gets misunderstood.

“I’ve been called ‘the foreigner trying to tell us how to do business.’

“I just want to be able to pass on the knowledge that I’ve been fortunate enough to pursue.

“I’m sure there are others that want to do it, but just don’t have time.

Ultimately, he says he is determined to keep sharing in public forums what he has seen work on his own land and has potential to help others on the island and beyond.

“The Cyclades have an opportunity to become a global model for regenerative island living.

“This isn’t about abandoning tradition; it’s about continuing it, with the intelligence of today and the urgency of tomorrow.”