At 92, Emmanuel Comino continues a lifelong mission that defined him, the reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures. Decades ago, he made a promise to Greece’s late Culture Minister Melina Mercouri — a promise that remains unbroken.

Last week in Athens, Comino travelled again for what he calls “the sacred cause,” joining an assembly of international advocates for the Sculptures at a special meeting with President of the Hellenic Republic Constantine Tassoulas and Culture Minister Lina Mendoni (who is due to visit Australia soon). The assembly brought together leaders from national committees across the world who champion Greece’s call for the return of its stolen heritage.

President Tassoulas praised the efforts of these committees and said they had shifted global public opinion in favour of Greece’s claim.

“Your initiatives and your advocacy have created a very favourable current of public sentiment for our vision,” he told them. He singled out the importance of influencing opinion in the United Kingdom, describing it as “one of the key conditions for the success of our goal.”

“Sooner or later the Acropolis Museum — described as a museum in waiting — will receive this enormous gesture from the United Kingdom, the return of the Sculptures. Reunification is not a matter of victory or defeat. No one will lose if they are returned, because this request concerns the global cultural community and is ultimately universal,” Tassoulas said.

The struggle

The assembly in Athens was part of ongoing efforts by the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures (IARPS), which brings together 20 national committees from 18 countries. Comino is the Association’s vice-president.

At the meeting, the Greek President outlined Greece’s readiness to receive the Sculptures, highlighting the Acropolis Museum’s “world-class facilities and Greece’s decades-long investment in the preservation of the Acropolis monuments.”

Tassoulas reiterated Greece’s willingness to collaborate with the British Museum, through rotating exhibitions and loans, to ensure Hellenic heritage is exhibited.

“Reunification is ultimately a matter of cultural justice,” President Tassoulas told the attendees.

A personal journey

For Comino, the fight is personal. Born in Rockhampton, Australia, in 1933 to Kytherian migrants, his early life was marked by adversity. At the age of four, his mother died. The following year, his father took him and his brother to Greece for a holiday — but World War Two broke out and they were forced to stay in Kythera for nine years before returning to Sydney.

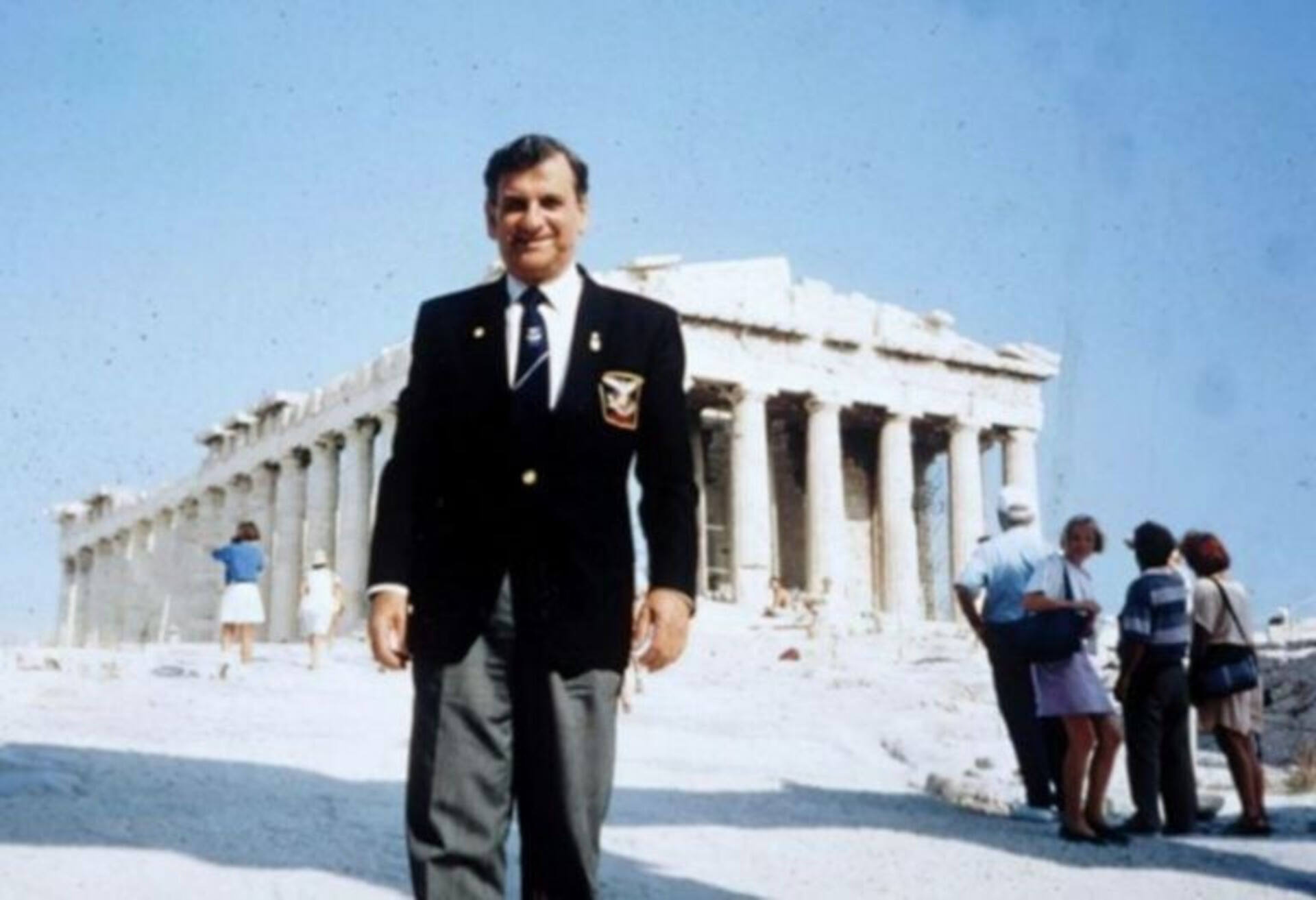

After working across various trades, Comino opened an insurance office in 1965. His first encounter with the Parthenon came in 1976 on a visit to Greece.

“I remember the moment clearly,” he recalls in fluent Greek. “I was overwhelmed and I immediately understood the damage [Lord] Elgin had done,” Comino said.

Elgin hacked off the Parthenon Sculptures between 1801 and 1812 with the acquiescence of the Ottoman colonial powers, which occupied Greece for 400 years until 1821. Elgin then transported the Sculptures from Athens to England. On the way, one ship sank with sections of the Sculptures.

The Parthenon Sculptures remain to this day, in dark and dank British Museum torn from Athens’ light their ancient home. The Sculptures, also often referred to as the ‘Parthenon Marbles’ became the lodestar for a global movement by post-colonial nations and Indigenous peoples to repatriate artefacts taken by Britain and other European powers during the height of modern European imperialism in the 19th century.

“Having visited all the European museums housing Greek ancient artefacts and treasures, I resolved to pursue their reunification,” said Comino.

Five years later, Comino founded the Australian Committee for the Restitution of the Marbles. That was 10 days before the famed actor and activist Melina Mercouri took office as Greece’s new Culture Minister when the Panhellenic Socialist Party (PASOK) won the 1981 elections. Comino immediately sent Mercouri his committee’s charter and pledged to join her in a coordinated global campaign.

Recalling their first meeting, Comino said he was at a reception in Sydney for Mercouri, who was visiting, and approached the official accompanying her and handed him his letter.

“Melina [Mercouri] read it, her face lit up. She crossed the room, embraced me and said, ‘My boy, never stop fighting for the Marbles.’ I replied, ‘I will fight until Britain sends them back, or until the day I die.’ We stayed in touch until her death.”

Ceaseless global campaign

For more than 40 years, Comino has travelled extensively, giving speeches, lobbying politicians, and rallying support from Greek communities worldwide. In 2002, Australian Prime Minister John Howard wrote that the Parthenon Sculptures “are an irreplaceable part of Greek heritage and identity,” and later raised the issue with British Prime Minister Tony Blair.

Comino’s passion remains undiminished at 92. “Only when the Sculptures are reunited in the Acropolis Museum will they reveal the full story,” Comino said.

For Comino, the cause is not just about marble or art, it is about intangible cultural heritage and above all, “keeping a promise”.

“I promised Melina [Mercouri], and I will continue to fight for this cause until the day comes.”