Around 4,500 years ago, people living across the Cyclades and beyond, would sail to Keros in the centre of the Aegean -an uninhabited island today- to participate in an enigmatic sacred ritual. During their visits they would leave behind a fragment of a marble Cycladic figurine, connecting distant communities through a shared spiritual practice.

Was Keros the first sacred island in the Aegean, more than 1,500 years before Delos assumed that role in the ancient Greek world? The evidence increasingly suggests it was.

“In archaeology, the more answers you find, the more questions you have,” Dr. Michael Boyd, archaeologist and co-director of the Cambridge Keros Project, told Neos Kosmos just days after completing the latest excavations on Dhaskalio and Keros, with exciting new findings yet to be revealed.

A ritual that connected the ancient world

Around a thousand figurine fragments have been discovered across two sites since the late Colin Renfrew, a pioneer in the world of archaeology, launched his life’s final project on the island in 2006 to uncover the secrets buried at the world’s earliest maritime sanctuary.

“Each of these fragments represents a single figurine.”

Dr Boyd explains that these fragments cannot be joined with each other and hence, “we know that the rest of the figurine isn’t there. It’s somewhere else. What Colin Renfrew hypothesized, and I think he was probably correct, is that these breakage events took place elsewhere on the other islands, and that just a single piece of the figurine was selected to represent the whole, and taken to Keros and deposited at these special deposits.”

This ritual was maintained over two or perhaps even three hundred years in this incredibly remote part of the world where the only means of communication was to get in a boat and travel from one island to another. Not an easy feat.

“It was a way of connecting people together, recreating a sense of Cycladic identity every time the ritual took place.”

The largest known complex in the Cyclades of that time

The figurine deposits are only part of the story. Dhaskalio and Keros (only a short distance from the tourist islands of Koufonisia) were joined together in ancient times creating a natural harbor with excellent views of the north, south, and west Aegean. Excavations have revealed that Dhaskalio was almost entirely covered by remarkable monumental constructions built using stone brought painstakingly from Naxos, some 10 kilometers away.

Naturally shaped like a pyramid, the ancient builders of Dhaskalio enhanced this form by creating a series of massive terrace walls that made it look more like a stepped pyramid. On the flat surfaces formed by the terraces, they constructed impressive, gleaming structures using imported stone.

More than 1,000 tons of stone were imported, according to the research team (led by archaeologists from the University of Cambridge, the Ephorate of the Cyclades, and the Cyprus Institute). Almost every possible space on the island was built upon, giving the impression of a single large monument jutting out of the sea. It is the largest known complex in the Cyclades of that time.

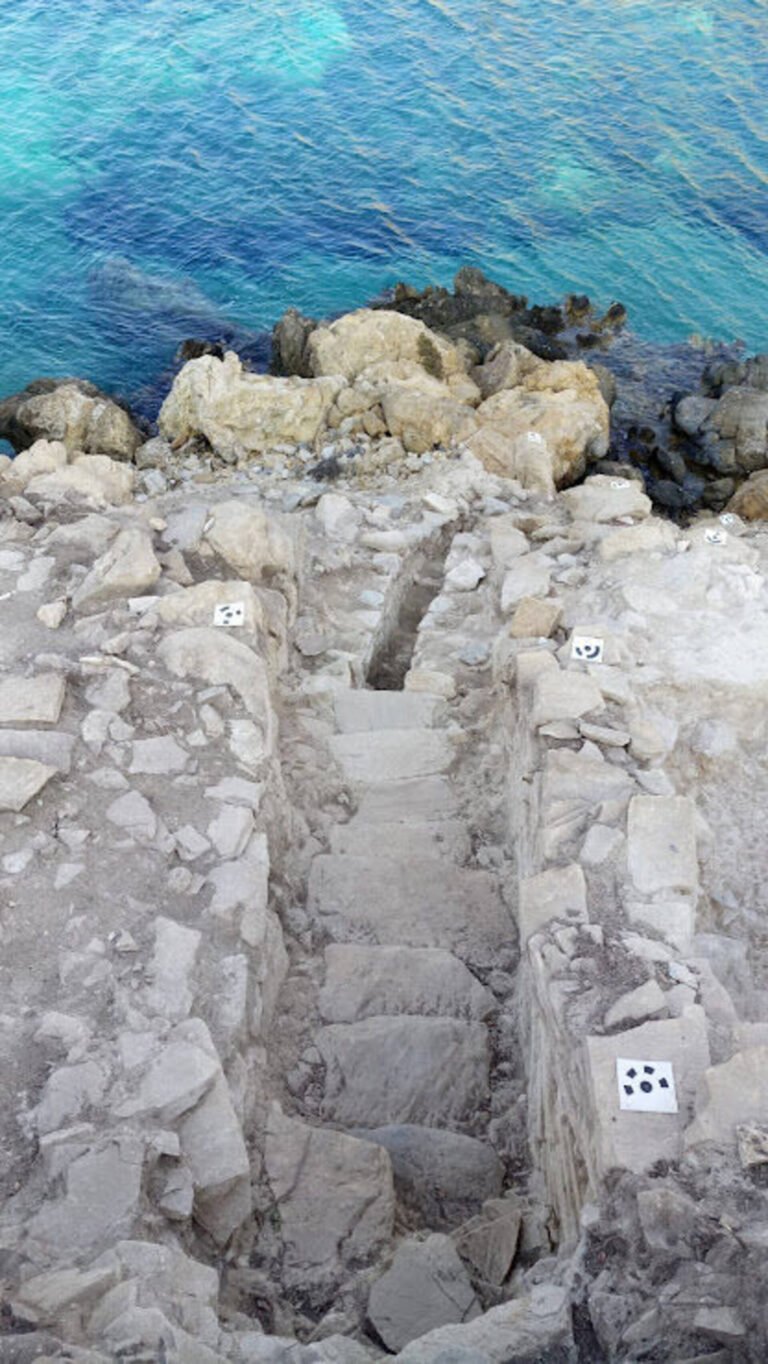

The site features a grand stairway and advanced drainage systems under the steps and in the wallsq , evidence of a highly sophisticated and well-planned civilization that thrived 1,000 years before the Mycenaean palaces.

Mysterious trade networks and thriving metalworking

Among the most remarkable finds are two workshops and installations for casting copper artefacts such as axes, chisels and pins, as well as spearheads and daggers, evidence of the community’s skill in metalworking, the era’s most significant new technology. Metalworking on this scale presumes a constant supply of raw materials from the western Cyclades or Attica, and social structures that allowed for learning and maintaining esoteric technical skills. The important question, Dr. Boyd stresses, is “where was all the finished product going?”

The mystery deepens with other extraordinary discoveries. Six carnelian beads, each traced to faraway origins in Egypt, Anatolia, and even the Indus Valley Civilization in present-day Pakistan. How far did people actually travel during the Early Bronze Age?

Findings also reveal the cultivation of olives and grapes, key crops that transformed agriculture in the third millennium BCE.

An unusual burial and unanswered questions

Near the ancient entrance to Dhaskalio, archaeologists discovered cremated human remains, a ritual completely unlike the contemporary burial customs in the Cyclades of that era. Why was this individual honored with such an unusual funeral, with remains buried symbolically at the gate of Dhaskalio’s strongest walls?

“These special deposits are only a part of the story,” Dr. Boyd says. “The nearby islands were all inhabited, and we’re trying to understand how the landscape and the seascape were used as a whole to create a single economy. What were people doing in their daily lives? And how does all of that come together to support the proto-urban centre that we have discovered at Dhaskalio?”

the excavation and gained valuable experience of up-to-the-minute excavation and scientific techniques. Photos: The Cambridge Keros Project

A snapshot of human development frozen in time

The site was abandoned for reasons yet unknown around 2200 BCE, leaving behind remarkably intact evidence of what human life looked like in that era.

“If you think about the second millennium, the Minoan world and the Mycenaean world, they are already quite well-developed, stratified hierarchical societies. And hence, the question in the Aegean has always been ‘how did we get there?'”

That’s why Keros is so important, Dr. Boyd states. “We have this amazing, precocious site where we clearly have the development of complex society taking place before our eyes. But the site is abandoned for reasons we’re still investigating, and therefore all the finds from that period are still there in place. They’ve not been destroyed by later occupation, and they’re waiting for us to excavate and find the answers to understand the 3rd millennium at Dhaskalio in a way that we can’t do at sites like Knossos, for example.”

A quantum leap

The third millennium BCE, not just in the Aegean but all over Europe, was a transformative time for human development. It was a period when distances became shorter, people travelled more and came into contact with more communities. Information became a commodity. It marked an important transition to more hierarchical and complex societies, a time when the concept of authority emerged and when mystical or religious beliefs were brought together and harnessed for the use of this authority.

“We see at our site, at Dhaskalio, the remarkable things that happened there,” the specialist in the early prehistory of the Cyclades and the wider Aegean explains.

“All the stone imported from Naxos, at least 1,000 tons of stone, meant hundreds of boat journeys, huge amounts of labor, incredible input that people made into creating that site, and lots of tragedy. People will have been lost at sea. There would have been accidents. The commitment to this is incredible.”

“We have moved from the question of ‘How do I build a house’ to ‘How do I build a city’ in a very short period of time. It’s a real kind of quantum leap. And we see this happening all over Europe.”

Technical Innovation in Aegean Archaeology

Colin Renfrew brought a different way of doing things to the Aegean, and in his final project on Keros, he brought together all his ideas into one particular enterprise, Dr Boyd continues.

All data from the excavations on Keros and the results of laboratory study are recorded digitally using a new system called iDig. This means that anyone on the excavation has access to all available data in real time. Three-dimensional models are created at every stage in the digging process and at the end of each season, the trenches are recorded in detail by the Cyprus Institute’s laser scanning team.

“We are trying to spearhead and showcase the advantages of this kind of integrated approach,” Dr. Boyd explains.

“The great thing about integrating the data is that you can correlate them. You see patterns emerging in very different types of data, because we have them all in a single 3D information space, which allows us to interrogate that.”

The project also takes a unique approach to publication. Rather than excavating for 10 or 15 years and accumulating unmanageable amounts of data, the team breaks their work into smaller phases. The current project is actually the fourth since 2006, with each phase followed by study and publication, ensuring that findings don’t remain buried in notebooks and hard drives.

The questions that remain

Despite decades of excavation, Keros continues to guard its secrets. Who was the individual cremated near Dhaskalio’s entrance, honored with a funeral rite completely foreign to Cycladic tradition? Where did the weapons and tools produced in those intense metalworking workshops ultimately go? What networks enabled a carnelian bead from the Indus Valley to reach this remote Aegean island? And perhaps most haunting of all, why was this thriving proto-urban centre, this focal point of spiritual and economic life, suddenly abandoned around 2200 BCE?

“Every time we do anything at Keros, it seems to open up new vistas and new research areas,” Dr. Boyd reflects.

“It’s like ripples in a pond. There are many more questions as we go forward.”

With each season of excavation, those ripples spread wider, revealing glimpses of a sophisticated Early Bronze Age world far more interconnected and complex than previously imagined, a world that, nearly 5,000 years later, still has much to tell us about how human civilization emerged in the ancient Aegean.