Democracy – the English word – is, as every schoolgirl knows, of ancient Greek derivation. Democracy – the thing – as it is practised around the world today is quite another matter – or rather matters. Indian democracy, say, is not by any means identical to Australian. As I write, some 600-700 million (sic) Indian citizens (out of a potential 900 million plus voters) have started a gruelling six-week rolling vote in the world’s ‘biggest’ democracy. At the same time the Prime Minister of Australia has announced the – single – day/date of his country’s next general election. These democracies are hugely different in scale, very different in modality, but still their national elections are taking place within democracies of the same generic type – indirect, representative, parliamentary democracy.

They managed things very very differently in ancient Greece! To the Greeks of Classical Athens or Mantineia or any of the 200-plus other democratic polities (out of 1000 or so in all, most not democratic) elections were not democratic at all – but oligarchic, that is, disproportionately favouring the rich and powerful few; there were no political parties – or governments; and all major public political decisions (the word ‘political’ is also originally of ancient Greek derivation) were taken by open vote of citizens present in person, that is in a word, directly. How are the mighty (ancient Greek democratic political systems) fallen!

Today, most of us are so ill educated and ignorant of the history and symbolic meanings of our often very disparate parliamentary systems that we can’t even tell the essential, qualitative difference between direct democracy and indirect, representative, parliamentary democracy. This – as I urged at the time, actually during the 2016 UK/EU referendum campaign – was possibly the single most tragic mistake made by the Tory government of David Cameron, aided and abetted by all too many of our professional parliamentarians.

Not that we in the UK are alone in suffering democratic deficiency syndrome but the actual and likely future consequences of the tortuous Brexit (aka Brexs***) process – still unresolved after nearly 3 years – are so dire that not a few of our UK commentators think there may be merit in at least contemplating the world from which the word ‘democracy’ ultimately came, the world of Classical Greece. Did they manage these democratic things better in ancient Greece?

The trial and enforced suicide of Socrates have historically been held up as a major, inexpungeable blot on the nearly 200-year record of Athenian democracy. What James Madison labelled ‘faction’ was in the view of the American Founding Fathers the besetting sin of Athenian-style direct people-power. But against those lucubrations and lamentations leader-writers and political commentators have turned again and again to one particular moment in the history of the ancient Athenian democracy as a possible counter-example, one of hope and possible inspiration.

READ MORE: Where does the West begin and end in Education?

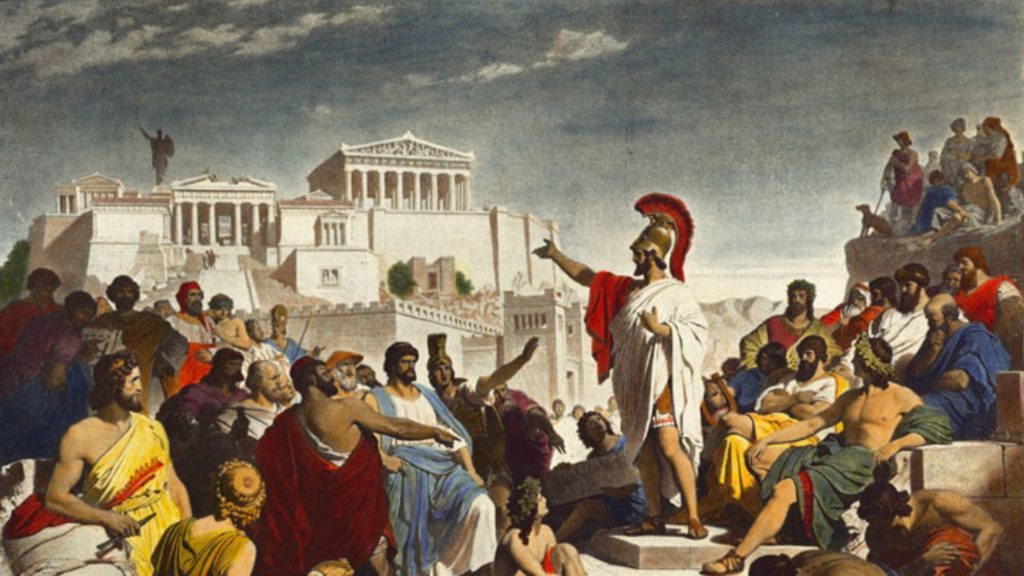

In 427 BCE Athens was four years into a major ‘world’ war fought together with its allies against Sparta and its allies. Sloganising was rampant – the Spartans declared as their war-aim to liberate Athens’s allies from their hegemon’s tyrannous yoke. But at bottom, as the war’s great historian and analyst Thucydides perceived, it was a war about power. Fear, greed, prestige: these were the real drivers on both sides. But there was a genuine ideological struggle at stake too – as again Thucydides starkly revealed. Broadly speaking Sparta, itself a peculiar, hierarchical military society based on exploiting unfree Greek people, lent its powerful support to anti-democratic oligarchic regimes, whereas Athens, itself a democracy, tended to support democracies of varying stripes within and outside its alliance. A major Athenian naval ally was the city of Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Like three of the other four Lesbian cities, Mytilene was an oligarchy, and its rich leaders wished with Spartan aid to exit the Athenian alliance – or ’empire’. Spartan aid was forthcoming, but the revolt failed and Athens was obliged to discipline Mytilene severely. But how severely?

Opinions among Athenians differed. Their hearts told them oligarchic Mytilene should be exemplarily punished – the leaders executed, many or most ordinary citizens enslaved. Their heads told them that only the ultra-oligarchs and their keen supporters should be executed or enslaved. On successive days the Athenians met in Assembly. On Day One they went with their hearts, on Day Two with their hearts – and heads. Yes, democracy of the direct Athenian kind allowed citizens to change their minds – for the better. But their democracy and their history are very far from being ours. The past is often, as in this case, a desperately foreign country.

Paul Anthony Cartledge is a British ancient historian, academic and A. G. Leventis Senior Research Fellow and Professor of Greek Culture emeritus of the University of Cambridge Faculty of Classics. He is also an honourary citizen of Sparta.