“If I create from the heart, nearly everything works; if from the head, almost nothing”.

These words of Belorussian-French artist Marc Chagall – who fused modernism’s aesthetic preoccupations with aspects of his own Jewish roots – were part of Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ speech at the inauguration of Athens’ new Goulandris Museum of Modern Art (on 1 October). Chagall was a close friend of the museum’s founders, Basil and Elise Goulandris – art collectors with a great passion for culture. It is quite befitting therefore, that after a 27-year struggle to realise this museum, it finally opened on Eratosthenous Street: the name Eratosthenous, is made up of the words ‘Erotas’ (love) and ‘Sthenos’ (strength), and so reflects the driving force behind this museum – the power of a genuine love for art – which initially motivated the museum’s founders to create the collection and to dream of its final Athenian destination. This driving force was also joined by that of the Goulandris Foundation’s staff, headed by Elise Goulandris’ nice Fleurette Karadonti (the foundation’s President), and the museum’s director Kyriakos Koutsomallis, plus his daughter Marie Koutsomallis-Moreau (the collection’s chief curator). They made the dream come true, because sadly, Basil Goulandris passed away in 1994, and Elise in 2000.

And this dream did not come without a price of course – the collection is estimated at around $3 billion, while the 11-storey building, designed by I.M. Pei (but with work also undertaken by the Greek architectural firm I&A Vikelas), boasts the highest museum standards. This priceless cultural gem in the heart of Athens, is a gift that offers visitors an exquisite artistic experience – the kind it didn’t have up till now: namely a permanent exhibition of works by the best of the most famous modernist masters and internationally renowned contemporary pioneers.

READ MORE: A modern art gem in Athens: Greece’s new Goulandris Museum opens its gates in Pangrati

A quick tour

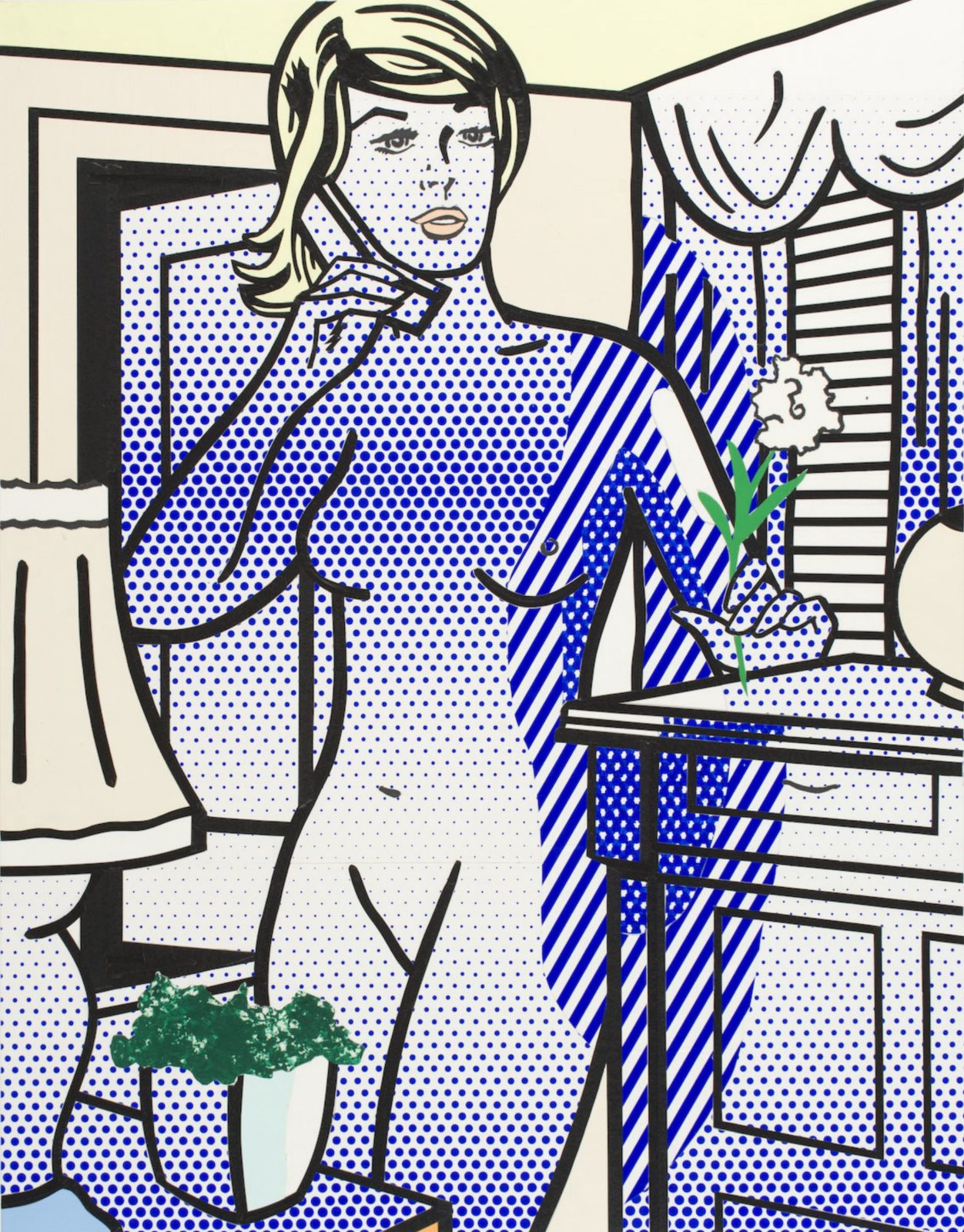

On the first floor, you find Cezanne, Rodin, Monet, Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec, Degas, Van Gogh, Miro, Picasso, Braque, Leger, Bonnard, De Chirico (et al). Here you will also find an exhibition of French furniture and Chinese objets d’art (15th-18th centuries). On the second floor you’ll find works by the best of the post-war contemporary pioneers (eg Pollock, Bacon, Nicholson, Lichtenstein, Giacometti, Saint Phalle). Further up, you’ll find a fine collection of Greek art on show, both modernist (on floor 3, with works by Parthenis, Ghika, Moralis, Tsarouhis, Tetsis et al), with a second space hosting large works by international contemporary names such as Ruscha, Kiefer and Takis. On the 4th floor you’ll find contemporary Greek art (Philopoulou, Rorris, Hadoulis, Tsoclis, Sorongas, Mantzavinos et al). In fact it’s so rare to find international names such as Picasso, with Greek names such as Ghika in the same museum. And what one realizes here, is not only the quality of the internationally acclaimed modernists and contemporaries, but also the quality of their Greek counterparts.

But the spotlight is also on an older masterpiece by El Greco, entitled ‘The Veil of Saint Veronica’, which is basically a portrait of Christ, and it is the first work the couple bought in 1956. It is also the first work you meet on the first floor, just before the modernists. Many have argued over the origins of El Greco – was he Italian, Spanish or Greek? But the fact that many preferred to call him ‘The Greek’ (because that’s what ‘El Greco’ means), rather than by his real name (Domenikos Theotokopoulos), suggests his true origins. But like the founders of this museum, he was an international Greek. He was also a pioneer, who influenced many later generations of artists, including the modernists. And so placing this work here ignites an interesting dialogue.

The exhibition of French furniture and objets d’art, completes this new museum’s creative profile. The collection tots up to around 800 works (including the objets d’art etc), 180 of which are on display at the moment. The plan is to change the exhibits on a yearly basis, so that the public will get to see all of them. There is also a space for temporary shows and visitors may also enjoy the museum’s library of 6000 art books, plus the unique museum shop. An amphitheatre for lectures/concerts, a children’s workshop, a small recording studio, plus two café restaurants (one which opens out into the urban garden, and the other on the roof, with a view of the Acropolis), also add more facets to this new cultural hub, which is already teaming with visitors.

READ MORE: British Museum asks Athens for sculpture loan

The Goulandris couple

As one views the exhibition, one also gets more curious about its founders: So what were Basil and Elise like? Marie Koutsomallis-Moreau describes her impression of Elise, in the present show’s catalogue: “Her beauty surprised me every time. Devoid of all vanity and ostentation, her elegance seemed to enlighten everything around her”.

She also describes Basil: “He spoke little, listened a lot, not at all embarrassed by silence. But as soon as he opened his mouth, I gathered all my concentration so as not to miss a word.”

You also get an idea of their personalities via the portrait of Elise by Marc Chagall, the first work you see upon entering the museum, displayed next to the ticket booths: She looks dreamy, as she also does in the portrait of the couple by Yiorgos Rorris, up on the 4th floor. The latter is a grandiose work, and although it presents the couple amidst some of their most treasured masterpieces, it also presents them with a distance between them (it is in fact a diptych). Elise, as radiant as the orchids by her side, looks into the distance (or the future?), with a radiant smile, but with a touch of melancholy in her eyes. Basil’s sharp eye pierces the viewer in contrast. From this work, one gets the impression that they were a case of ‘opposites attract’.

The museum’s trials and tribulations

Interestingly enough, there is a Konstantinos Mitsotakis at both ends of Athens’ Goulandris Museum of Modern Art’s history, with the son inaugurating the establishment that his father had initially given the go ahead for: It was back in 1992, when the present Prime Minister’s father (also called Konstantinos Mitsotakis) was in power, that Basil and Elise Goulandris proposed to the government the creation of a museum in order to house their collection in Athens. Although the government agreed to the proposition, the museum’s materialisation was impeded by a series of obstacles: on the first site allocated (on Rigillis Street), the Lyceum of Aristotle was discovered when digging started, then on the second site allocated (Rizaris Park), the residents protested because they wanted to keep their park. In 2009, a site on Eratosthenous Street was allocated, but problems developed when underground water was discovered during construction (something that has also stalled the completion of the National Gallery’s ongoing extension/renovation). In addition to this, court cases and family feuds also hindered the museum’s completion: Basil Goulandris had not made a will before his death, and the will left by his wife Elise was also elusive on the subject of the collection. A mysterious sale of 83 works from the collection, connected to the Panama Papers scandal, plus the claims of Elise’s niece Aspasia Zaimis to a share of the collection, complicated matters further.

READ MORE: Philanthropist Niki Goulandris has died aged 94

Roy Lichtenstein, Nude with White Flower

Jackson Pollock, Number 13 1950.

Alberto Giametti, Portrait de Yanaihara.

Costas Tsoclis, Tree.

Auste Rodin, L'Eternel

Alberto Giacometti, Femme de Venise V

Paul Gauguin, Nature morte aux pamplemousses

Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, Balcony with Horizontal Pilasters

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled

Amedeo Modigliani, Cariatide

Constantinos Parthenis, Harmony

Pablo Picasso,, Femme Nue aux Bras Leves

El Greco, La Santa Faz

Vincent van Gogh, Nature morte a la cafetiere

Vincent van Gogh,, Les Alyscamps

Vincent van Gogh, Cueillette des Olives

Fauteuil “à la Reine” Louis XV (2)

Marc Chagall, Portrait de E.B.G.

Francis Bacon, Three Studies for Self-Portrait

Greek diaspora’s love of the motherland

Basil and Elise Goulandris met in New York in the late ‘40s. Elise was a beautiful young student there, escaping from her middle-class Athenian environ and its conventional expectations of her, while Basil and his brothers, had taken on the shipping company of their father, the Orion Shipping & Trading Company Inc, that had been founded in 1946. By 1958, the company had 82 ships. The Goulandris couple had everything they could dream of – the jet-set life of shipping tycoons, with property dotted around the world. The only thing they didn’t have in fact, was children. And so, instead, they dedicated themselves to art. Their home in Paris became a meeting place of the crème de la crème of the business world but also of the arts and letters: From Callas and Baryshnikov to Chagall and Balthus. It was in 1968, in Paris, when Kyriakos Koutsomallis met the Goulandris couple, when he was studying there. In 1972 he became their personal secretary and later the director of the Goulandris foundation.

As with many diaspora Greeks, Basil and Elise had a deep love for their motherland, and always wanted to offer something back to Greece, despite their international lifestyle. They therefore created Greece’s first Museum of Contemporary Art in 1979, on the island of Andros (Basil Goulandris’ birthplace). In 1981, the Archaeological Museum followed, and in 1986 the New Wing of the Museum of Contemporary Art was also created on Andros. Now, the new Goulandris Museum of Modern Art in Athens, completes their efforts posthumously, to provide the Greek public (and those visiting Greece of course) with an absolutely fabulous cultural gift that will enrich their lives profoundly.

The new Goulandris museum is the new kid on the block, of a growing cultural scene in Athens, bolstered by private funding (consider the Onassis Cultural Centre, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Centre, the Neon Organisation, Deste foundation), but also by the state: the National Museum of Contemporary Art, will be officially re-inaugurated in February, plus the National Gallery’s much-awaited revamp is to be completed by 2021. Such endeavours are steadfastly making this city not just about its ancient cultural heritage, but instead, providing visitors with one of the most interesting and varied of cultural vistas on offer in a modern metropolis.

* The Goulandris Museum of Contemporary Art is at 13 Eratosthenous Street, Pangrati in Athens. For more information, visit https://goulandris.gr/