In Kornaros’ time the island of Crete, once part of the Byzantine Empire, had been a territory of the republic of Venice for about 400 years.

Venice had acquired this Greek island after crusaders from western Europe captured Constantinople and divided up its empire in 1204.

The Byzantines re-occupied their capital in 1261, but many areas, including Crete, remained under western rule.

On the island, large estates were distributed among settlers from Venice, who became a colonial elite.

For over 150 years, members of leading Byzantine families on the island led frequent revolts against Venetian rule. Meanwhile, over the generations the descendants of the Venetian settlers were largely assimilated and spoke Greek as their first language.

The majority of Cretans were small-scale farmers and stockbreeders, owning little or no land of their own and often brutally exploited by both landowners and Venetian officials. But in Kornaros’ day the north coast towns, especially Chania, Rethymno and Candia (today’s Heraklion), were flourishing, largely due to the export trade in products such as wine and cheese.

READ MORE: Celebrating Erotokritos Year 2019 (Part 1): What’s it all about?

Among the nobility and the prosperous citizens there were people with leisure, education, and, often, close contacts with Venice and the culture of Renaissance Italy.

These conditions and contacts helped to bring about the developments in art and literature that are sometimes known as the Cretan Renaissance. The most famous product of this movement was the artist Dominikos Theotokopoulos (El Greco), who served his apprenticeship in Crete before pursuing his career in Italy and finally in Spain.

Achievements in literature were also extremely important, though less well known outside Greece. In Kornaros’ time, Cretan writers were experimenting with a new poetical language, based closely on the spoken dialect of their island. They drew inspiration from the rich oral tradition of folksong (δημοτικά τραγούδια), as well as from their readings in contemporary Italian and medieval Greek literature. A similar movement on Venetian-ruled Cyprus had been cut short by the Ottoman invasion of 1570-71.

Fine works of poetry and drama came one after the other. Around the time Kornaros was working on Erotokritos, an unknown poet wrote a much shorter narrative poem, The Shepherdess, which was first printed in 1627 and remained a best-seller for over 200 years. Equally successful was the tragedy Erofili by Georgios Chortatsis, the “father of modern Greek theatre”, first printed in 1637, and the anonymous religious play Abraham’s Sacrifice, probably written around 1600 but not printed until late in the century.

READ MORE: Venetian odyssey

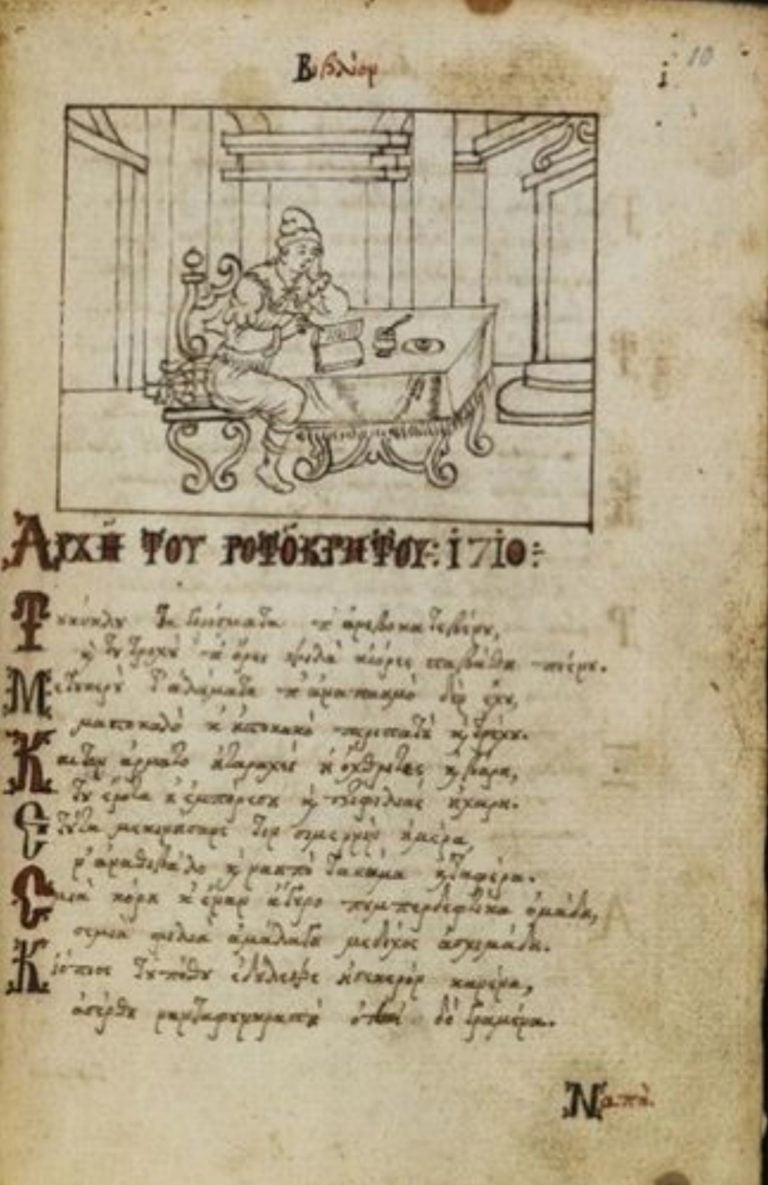

All these and several other Cretan works were widely read in print, and became part of Greek popular culture. Others again were not printed but circulated in manuscript copies, some of which survive to this day.

Dr Alfred Vincent is a researcher and academic who has taught Modern Greek at the University of Sydney. He has given lectures and seminars at institutions around the world and has been actively involved in organisations of interest to the Greek Community.