We are all spending more time at home. It’s a great time to get around to those household tasks you’ve always been putting off. But it’s also a time to get into some good old home cooking. And when we think of cooking many of us will reach for those tried and true cookbooks we’ve collected over the years. One favourite of mine is Tess Malos’ ground-breaking Greek Cooking. But another is one that many readers may not be that familiar with. It’s a cookbook which really expanded the appreciation of Greek cuisine to the English-speaking world.

The book I’m referring to is Elizabeth David’s A Book of Mediterranean Food which was first published in 1950 and has been in print ever since. This book burst onto the dreary, food-rationed environment of post-war Britain bringing an exotic and entrancing vision of life and food across the Mediterranean, including Greece. Soon Elizabeth would be both a literary and culinary celebrity, with more cookbooks and newspaper columns.

Her writings were both travelogues and practical guides to cooking, her recipes drawn from her travels throughout Europe in the years immediately before and during the Second World War. What is little appreciated is the part that Greece played in her culinary education and success. For it was to Greece that this young English woman came in these dangerous days and who experienced the food and hospitality of its people, particularly on the Cycladic Island of Syros. And this experience is reflected in her writings, with tales of where and how she first tasted these culinary delights, telling a story of Greece through food – of eating by the sea, of drinking ouzo with your meze and of the village fourno.

READ MORE: How the Mediterranean diet became No 1 — and why that’s a problem

The young and beautiful Elizabeth came to Syros as part of an ill-fated sailing voyage across the Mediterranean, with her then lover Charles Gibson. Such a cruise would have been a great idea but their timing on the eve of the war couldn’t have been worse. Having their boat confiscated and being arrested briefly in Mussolini’s Italy, Elizabeth’s sojourn in Greece commenced with her arrival in Athens via Yugoslavia.

They arrived in Athens in the days prior to the Italian declaration of war. Walking around the city Elizabeth would write of the lively late-night entertainments, the locals sitting in their cafes drinking ouzo or brandy until 9pm, then dinner followed by a return to the café to eat ices and sweet cakes with their Greek coffee. It was in Athens no doubt that she experienced traditional stuffed tomatoes, this baked dish filled with a mixture of rice, onion, currants, leftover meat and seasoning, “a la grecque” as she wrote. She would write of venturing into an Athenian taverna kitchen and savouring the sight and smells of the dishes cooking in “enormous shallow pans”, tomatoes and pimentos and zucchini blending into “the marvellous smells which assails one’s nose, and the sight of all those bright coloured concoctions is overwhelming. Peering into every stewpan, trying a spoonful of this, a morsel of that, it is easy to lose one’s head and order a dish of everything on the menu.”

READ MORE: Greek folk festivals events, cuisine, at the heart of wide-ranging book

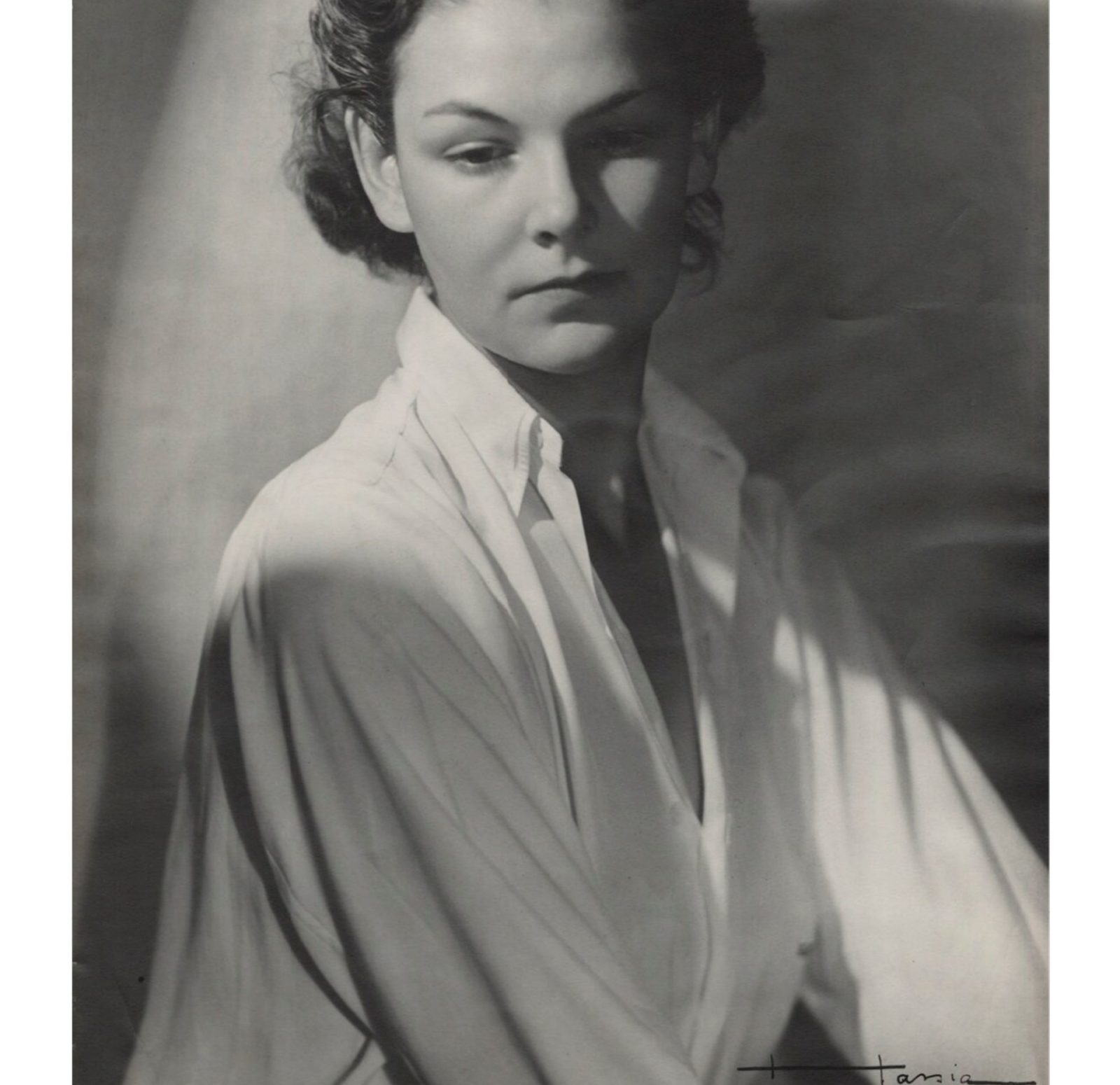

Elizabeth David in 1960, taken by an unknown photographer.

Elizabeth David Chelsea in the kitchen

Soon they were on the move again, choosing Syros as their haven. When Elizabeth sailed into the harbour of Ermoupolis – the city of Hermes – the capital of Syros, she would have been impressed by the neoclassical architecture of the town and its mansions, reflecting the wealth and prominence of earlier times. And maybe she heard the music of Markos Vamvakáris, the “patriarch of Rebetiko”, born here in 1915.

Elizabeth eventually found a small cottage on the village of Vari on Syros’ southern coast. She would write about the abundance and variety of local ingredients with which she learned to cook here, ranging over fresh bread, olive oil, olives, salt fish, hard white cheese, dried figs, tomato paste, rice, dried beans, sugar, coffee and wine. Fresh vegetables and fruit were obtained from the garden of the local tavern owner. She would write that while meat was available on special occasions, fresh fish would be brought to her regularly by a local fisher boy, from small fry or inkfish to occasional treats of langoustines and the famed Aegean barbounia (mullet). It was this exposure to good quality, simple ingredients which would become the hallmark of

Elizabeth’s recipes and writing. As she wrote later:

“Greek gourmets know exactly where the best cheese, olives, oil, oranges, figs, melons, wine and even water … are to be found, and go to immense trouble to procure them.”

READ MORE: Niko Koulousias: the Greek chef cooking at Harry and Meghan’s wedding

Afteli Beach, Lefkada

The perfect late lunch at Gytheio.

Syros 1904

Her experience of island life is also revealed by her description of the shared use of the village oven or fourno. This was necessary as many houses lacked an oven, so dishes like lamb on the bone would be prepared early and taken to the village oven for cooking. As Elizabeth writes “… they emerge deliciously cooked, better than they could ever be in a gas oven.”

Her absorption in local culture is clear from her description of many recipes, but especially that for baked partridges, cooked “klepthi fashion”. The bird was seasoned with mountain herbs, wrapped in paper, “with a little fat and any vegetables that may be available” and cooked in an earthen pot for two to three hours, releasing the best flavour of meat. She wrote how the method was known “all over Greece” as klepthi cooking, the food of the resistance to Ottoman rule. And in words referring to the brave role of the Greek resistance during the Second World War, the klepthi tradition was that of “the original Resistance Movement in fact.”

And who cannot appreciate her writing of sitting at a taverna table on the sand with her feet almost in the water tasting her meze and drinking her ouzo, her thoughts no doubt returning to Syros. She wrote of Greece’s sweets – of rizogalo and baklava, of Cyprus’ stuffed walnuts in syrup and loukoumades – as well as some of the memorable ingredients of Greek cuisine. What food writer could visit Greece and not fall in love with wild rigani (oregano)!

Elizabeth wrote of the name’s Greek origin in the phrase “the joy of the mountains” and its being “much stronger perfume” than British marjoram.

In words familiar to all who have enjoyed Greek hospitality, Elizabeth wrote of being offered glyko served on a tray with a glass of water and small cup of sweet Greek coffee. She wrote how this was always offered to strangers arriving at a house as “a symbol of hospitality which must on no account be refused.”

Years later she could not bring herself to dispose of an old jar of sweet walnut glyko just in case visitors from Greece arrived! And with words that will ring true to all who have experienced Greek hospitality Elizabeth would write of Greek hosts that:

“They are also exceedingly generous and hospitable, and when they see that a foreigner is appreciative, take great pride in seeing that he is entertained to the very best which Greece can offer.”

The arrival of the war and German invasion in April would see Elizabeth follow the exodus of many others, civilians and soldiers, first to Crete via Mykonos and Ios, and from thence to Alexandria in the days prior to the attack on Crete. Her war would continue, with her service with the Allied forces in Egypt, where she met the future writers Lawrence Durrell and Patrick Leigh Fermor – but that is another story. Meanwhile behind in Greece Elizabeth’s idyllic experience would be submerged in the destructive occupation, its people suffering terrible famine and reprisals.

READ MORE: Hats off: Six Greek-owned restaurants make Australia’s Good Food Guide for 2019

Syros, Ermoupolis.

Vari Beach.

After the war, when she made the first steps in her new career as a food writer, it was to those tavernas and the village women of Syros that she would return for inspiration. Her writings would inspire others to come to Greece and experiences its hospitality and culinary delights in person. As Elizabeth wrote “the cooking of the Mediterranean shores, endowed with all the natural resources, the colour and flavor of the south, is a blend of tradition and brilliant improvisation.”

What better description for the flavours and foods of Greece.

Along with George Johnston, Charmain Clift, Durrell and Leigh Fermor, Elizabeth David deserves to be part of our philhellenic pantheon. So, here’s a toast to Elizabeth David and “her war”, and to the hospitality of the people of Syros, who helped her to bring the joys of Greek cooking to so many across the English-speaking world.

I would like to dedicate this article to Dora Gogos, who loved the food of her homeland and with whom I was fortunate to have shared a lovely lunch in Oakleigh, talking food, travel and history. Vale Dora.

* Jim Claven is a trained historian, freelance writer and has been Secretary of the Lemnos Gallipoli Commemorative Committee since its founding in 2011. His most recent publication is Lemnos & Gallipoli Revealed: A Pictorial History of the Anzacs in the Aegean 1915-16. For those interested in reading more about Elizabeth David, Jim recommends Elizabeth David’s A Book of Mediterranean Food and An Omelette and a Glass of Wine, Artemis Cooper’s Writing at the Kitchen Table and Lisa Chaney’s Elizabeth David. He can be contacted at jimclaven@yahoo.com.au