Author Stella Tzobanakis brings to life the incredible bravery shown by the Australian and New Zealand soldiers and by the people of Crete who risked their own lives by harbouring these soldiers during the invasion of Germany in World War II.

With the kind permission of Stella Tzobanakis, Neos Kosmos presents an edited excerpt from Chapter 7: Refuge and Resistance from her book, Creforce the Anzacs and the Battle of Crete.

BECOMING CRETAN

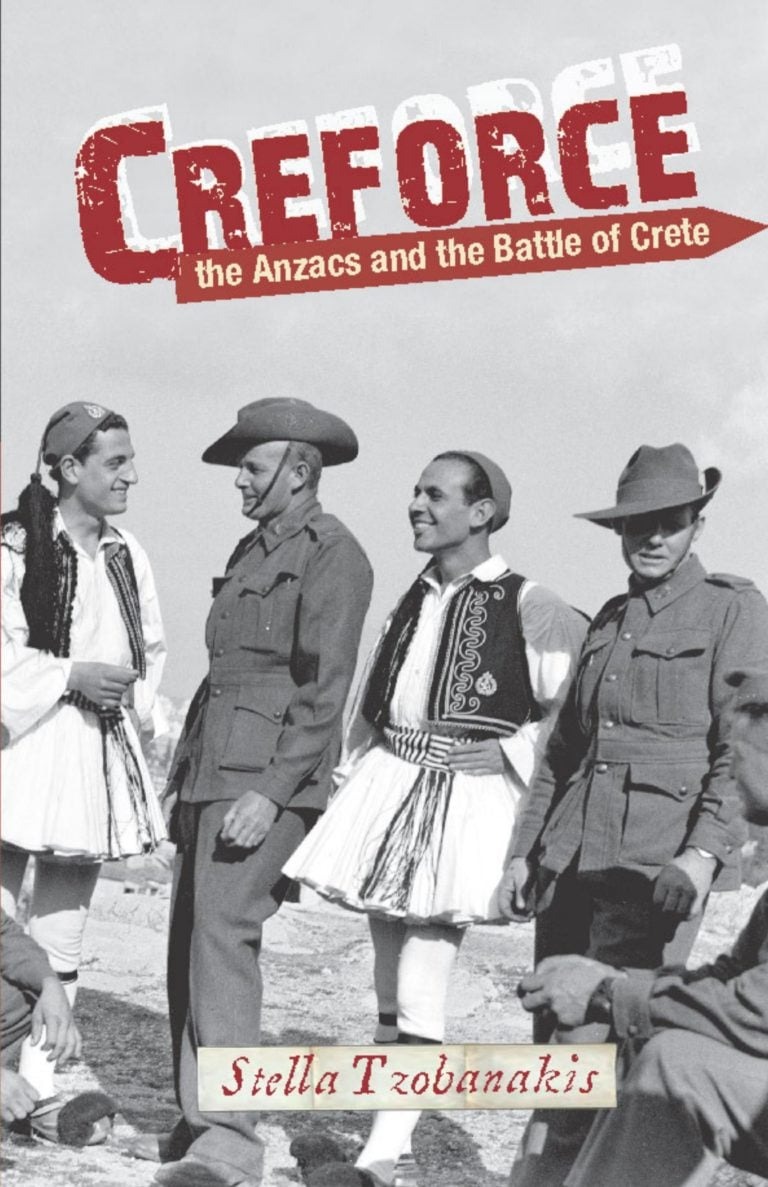

For most Cretans, meeting an Allied soldier was their first contact with anyone from Australia, New Zealand or Britain. When they took the men in, they told them to take their clothes off first so they could burn them. They then dressed them to look like Cretan shepherds.

Whatever was left of a soldier’s khaki shorts and shirts was replaced with a pair of black stivania for walking across the mountains, a black sariki to wrap around his head, a black shirt and vrakes with a large mahera wedged into the belt that held them up. Some soldiers, such as Charles’ (Jager) friend Ben (Travers), were disguised as old Cretan grandmothers. It was a difficult identity for Ben to take on because he was a smoker and Cretan grandmothers don’t smoke! Consequently, he was not given any cigarettes.

To evade their pursuers and protect their saviours, the soldiers had to blend in with the villagers. The Cretans taught the men what they could of the Greek language and the Cretan dialect, as well as Greek traditions such as crossing oneself in the Orthodox way from right to left. The men assumed forged Greek identities and fake names such as Charles who chose Kyriakos from a book of saints. He was told his name meant Sunday and that this was a special name because Sunday was a holy day.

During their village stays, the soldiers slept on tree branches or in caves just outside the village in case German soldiers raided overnight. Many injured and ill men, such as Dudley, were quickly nursed back to health with good food, rest, and having tsikoudia rubbed into their feet and back.

Soon enough, many of the sheltered soldiers were transformed once again into pallikaria (warriors). With many of them now sporting Ned Kelly-like beards and thick moustaches, they set out again to find a way off the island, but they could only succeed with the help of the Cretans.

After receiving blessings from the women of the village who gave the sign of the Greek cross in front of the soldiers and said O Theos mazi sou (God be with you), the men were guided by a Cretan male from village to village either on foot or by mule, to be handed over to others who would feed, hide and guide them. The village of Asi Gonia was an especially good hideout as its inhabitants were good at being tight-lipped. It was also such an isolated and remote village that the German soldiers believed it was impossible for Allied troops to live there, especially in the winter. This made it the safest way for escapees and guerrilla fighters to get across the nomoi or districts of Hania and Rethymnon. So willing were the Cretans to help, that to Lewis, ‘it seemed that every child, every goat and every dog’ was determined to escort him. The fleeing soldiers never stayed too long in the one place, so as to minimise danger to those helping them. They always travelled solo or in very small groups in order not to attract attention.

READ MORE: Survivor’s tale of the German massacre

Some soldiers could not avoid standing out. Drinking too much wine usually led to their undoing, especially if they went outside and started singing songs like Waltzing Matilda or It’s a Long Way to Tipperary. The villagers would shout at them to be quiet and go and hide but many times the soldiers paid no attention.

‘BAD GREEKS’

Others had to flee from their hiding spots after word spread that ‘bad Greeks’ or traitors had reported local activities to the Germans. Traitors were enticed to collaborate with the Germans by the offer of large rewards for the capture of an Allied soldier. As well as money, the Germans used food as an incentive for Greeks to spy on their fellow countrymen. They also released Greek prisoners from jails and, in exchange for cooperation, offered protection to those with a vendetta on their head for stealing sheep or committing some other offence against a family.

Captured Allied soldiers were either shot or sent to prison camps in Greece. Others died from illness, or from injuries sustained while on the run. The rest were helped by Cretans to find their way to spots around the island where a Greek crew would be waiting to take them away by boat, or to a location where the soldiers could steal a boat to try to escape on their own.

*Creforce the Anzacs and the Battle of Crete, by Stella Tzobanakis, is available at http://stelitsahome.bigcartel.com