Hundreds of thousands commuters read an interview with her in the free DB Mobil magazine laid out in the hundreds of high-speed inter-city trains on the go daily up and down the country in May and June this year; she graced the cover. (The sub-editor had fun with his rhyming headline: Die coolste Frau der Tagesschau (The coolest woman of the Tagesschau).

Many have read the two autobiographical books she’s written, attended her readings from them all over the place, listened to audio of her first book, and have seen her in countless newspaper interviews, too numerous to catch up with.

Tuning in to her podcast about What are good Germans? in which she interviews prominent folks with a migrant background – a phrase the recently turned 45-year-old loathes.

A veritable ‘love Zervakis season’ seems to be blooming about the daughter of immigrant bicycle, fountain pen and shoe assembly line labourers, born in the working class Hamburg borough of Harburg.

There wasn’t much money about in the family of five – Linda has two brothers – so that she had to wear the hand-me-downs of one of them. The three kids shared a room. A chapter in Linda’s first book is called “And give us this day our daily bread”. Her childhood really must often enough have been a daily struggle to make ends meet.

When father Christos Zervakis lost his job, the parents opened a kiosk in Harburg, in which Linda and the boys helped out until she was 28. Her father, having died when she was 14, left his widow to cope alone – spending up to 15 hours a day 24/7 in the small business. After so long a working day, every day, there wasn’t much time for conversation with the kids in Greek.

READ MORE: Michelin-starred chef Andreas Mavrommatis and his ’45 Recipes from Greece, Made With Love’

That kiosk inspired Linda’s first book, Die Königin der bunten Tüte, (The queen of the colourful paper bag), which contained an assortment of sweets.

It was a window on a multicultural, trans-classes society, a micro-cosmos, which greatly shaped her, Linda stresses; it was a great leveller, where down-and-outs and smart-suited well-to-do city professionals shopped elbow to elbow in a cosmopolitan harbourside and industrial suburb some Hamburgians turn up their noses at.

The reader meets types like former club bouncer Johnny, who stabbed to death a pimp out of jealousy and did time for it. The ex-jailbird trying to resocialise is just one of many in the borough with their hearts in the right place, braving their drab lives with warmth, solidarity and not least with humour.

Humour lights up the author’s storytelling.

With a loving wink, she portrays her mother’s idiosyncrasy in never quite making friends with the German language and inventing highly creative words of her own.

But Chrissoula Zervakis made sure her daughter got a good school education. Linda attended a German grammar school as well as a Greek school. She was such a good learner, she skipped one grade.

All the same, school was no picnic. Fellow pupils would call her “Tzatziki” and even beat her up, firming her iron will to escape from that milieu.

READ MORE: Sublime Trieste, a mosaic of nationalities with haunting Greek remnants

It taught her a lot about life, she says.

Migrants, jobless, “some who tossed back herbal brandy for breakfast”. And, of course good, cordial types who look out for each other and for 20 years bought their Reval filterless smokes, fire pots and colourful assorted sweets from the Zervakis family.

Linda was lucky to attend a good school, had a German nanny and the unbreakable determination not to be looking out of the little booth for ever. The rest of the story she tells about that phase is charming, funny, sad and always a slice of life as it really is.

Growing up with a nanny and with her parents putting in the gruelling long work hours she spoke more German than Greek and it’s the stronger of the two languages. The dual-national speaks it better than many non-migrant (real?) Germans I know. A lovely deep voice, easy on the ear, her speech surgically correct. Listen to her here:

https://www.facebook.com/ndrdas/videos/305500200675001

When occasionally – like all broadcasters do from time to time – she fluffs some words on air she charms it away with a beg-pardon spoken through a 100-Watt smile as broad as a karpusi is long.

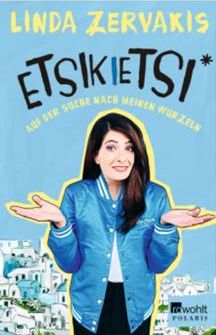

Linda feels half-German, half-Greek and in her second book, Etsikietsi – Auf der Suche nach meinen Wurzeln (Etsikietsi – Searching for my roots) she tells of several weeks holiday spent in Greece with her mother, Chrissoula (Chrissi), which morphs more and more into a journey into the past, rebonding mother and daughter so very closely that they can tell each other (almost) all of their dreams.

Chrissi Zervakis, too, wanted out of her Greek village but her father Kostas stopped her attending the acting school in Thessaloniki, although her acting talent had been spotted. Instead she was to learn to be a housewife to improve her chances on the marriage market. If necessary, a marriage would be arranged. End of dream, start of real life.

Chrissi wrote a diary about her hurtful experiences that Linda found one day under ironed crocheted blankets. “When I read that, it became clear to me that I’m living her dream. Which is why I decided to write this book and dedicate it to her. Mama, I’m going to put up a memorial to you [she said looking straight into the camera in a TV chat show]. So perhaps it’ll make her feel that coming to Germany was worth it after all. They planned to stay two years and then return to Greece. But then my big brother, me and my smaller brother came into the world and so they stayed.

“And now there are the grandchildren and so much has changed in Greece that she no longer wants to return to the home country.”

Having to work around Corona safety rules and presumably having to cancel some bookings, Linda takes that book far and wide across Germany to read from it to paying audiences.

Linda Zervakis has been one of the 8 p.m. Tagesschau anchors since May 2013, the first descended from migrants. Why does that matter, why can’t they just say, a new Tagesschau presenter, she grouses almost every time that’s said.

“I think that’s totally useless. I never had it [happen to me] before. I never had to present for a job saying ‘Hello, my name is Linda Zervakis and I have a migrant background’. It didn’t happen in school nor in an advertising agency. Not in radio, either. It only became an issue in connection with the Tagesschau,” she recalls the absurdity of the media finding it worth mentioning that another new female newsreader is the first with dark brown hair.

After graduating her Abitur (equivalent to Australia’s Year 12 Senior Secondary Certificate of Education) Linda worked as an advertising copy writer. Since 2001 she’s been a journalist and news reader at Hamburg-based NDR (Northern German Broadcasting), which airs the Tagesschau nationally.

In her weekly hour-long podcast Linda Zervakis präsentiert: Gute Deutsche (Linda Zervakis presents good Germans) she discusses migration with well-known personalities with a migration background, that is, people carrying more than one culture. “I ask them whether that’s caused them problems and what the benefits of two or even more cultures are. It can be chatty or also get quite serious.”

Some of her interlocutors have been a singer-songwriter, Mark Forster (of mixed German and Polish origins), the editor-in-chief of a highbrow weekly newspaper, Giovanni di Lorenzo (German mother, Italian father) and Cuban multi-talented stylist, Jorge Gonzáles.

“[People think] only those who are very successful at something can be good.” But perhaps someone like that also had great problems. Bicultural Linda adds, “if you’re awarded the trophy for the newest recording, the newest book or the newest film the other stuff is forgotten. That’s why the idea was to show: look, although that person got where they are, it wasn’t clear-cut that they would.”

The subject of the conversation depends on who it’s with, but some elements are in each episode. “[For example] we ask people on the street what they associate with the country our guest is from, say Syria, Poland or Italy.” Then journalists and culture workers do a thumbnail profile of the countries.

READ MORE: Opinion: A parallel universe – Growing up Greek in the 50s and 60s

What does she want readers of her books and listeners to her readings to take away? “Well, that the family kept reinventing themselves. And most of the relatives in Greece don’t have much money, but they’re happy. I’d like to take a leaf out of their book. They skip cheerfully through life although the financial crisis put them through some really ghastly years. And here’s me coming from prosperous Germany with a nagging mentality getting worked up over trivialities. Sometimes that’s almost shameful.

“Their communal cohesion is way better than ours. For example, financially strapped friends in Thessaloniki hosted dinners for each other [in their homes] instead of going to restaurants. It gave them the feeling of doing something together.

“It’d be good to now and again clap our eyes on the simple things in life.”

How was it for her as a prominent Greek TV personality many Germans slagging off about Greece during its financial crisis? “It was really awful. In many newscasts I had to read something [about this]. It wasn’t always easy for me not to show a reaction. But that’s demanded in the Tagesschau. I was also shaken by some of what one read about Greece. They really bashed [the country] and fed the stereotype of the lazy Greek.”

Is her mother proud of her career? “Oh, I think so. She set the alarm clock during my first nightshift and she cried when she saw me.” What traits ascribed to Greeks does she recognise in herself? “I can be very impulsive. I laugh very loud, I can lose my cool when driving. Most times I get a hold on myself again because I don’t want to end up as ‘the foul-mouthed Zervakis’ in the [mass-circulation tabloid] BILD-Zeitung.”

And what’s typically German about her? “The discipline. I’m punctual and I keep my word. When I say 3 p.m., that’s when I come. That’s different in Greece. There it’s ‘What? We agreed on afternoon, didn’t we?‘”

Given the flood of grim news she has to present, how does the devout Orthodox Christian manage to keep her faith? In her book she describes the Tagesschau as something akin to a big religious service. “After the broadcast I often think to myself, ‘oh my god, how really sick this world is’.” Everyday family things help her then. And detachment is indispensable to the job.

Her faith is an important pillar for her, Ms Zervakis has emphasised in interviews. Whereas in Greece the church belonged “completely self-evidently” to life and didn’t question as much “as it often is the case in Germany”.

“I’m Greek Orthodox. … My family are very devout, my parents even a lot more than we kids. Faith to me is like a soft wrap-around mantle that always keeps cocooning me. I believe that there is someone, a superior being.”

It was a great help when her father died when she was 14.

“That grew me up with a jolt. My faith was the pillar that carried me.”

Linda still has two big goals: presenting her own TV entertainment show and owning and running a guest house in Greece. “A bed and breakfast because I just can’t cook, but I can manage a breakfast.”

Ms Zervakis is married and mother of two children. Her husband, Guido Maria Kretschmer, is a reporter at NDR, the same broadcaster that employs his wife.

Linda Zervakis’ story is especially interesting against the background of ongoing debate about integrating immigrants. It’s helping to make people think about how to relate to people from other countries, but also one’s own adjustment conflicts. And she has underlined how decisive a key to social integration education is.

- This article was contributed by a reader of Neos Kosmos in Germany.