Did you hear the one about the 87-year-old Greek man who went to hospital emergency for anaemia and came out with a catheter? Did you hear the bit about how he tried to get the catheter removed? It’s a ripper. It has all the elements of a Greek epic.

There are elderly Greek men holding each other in public hospital urology wards. There are doctors of Greek heritage offering exceptional care. There are simulated soccer kicks. There is a small Greek feast.

My father Spiro’s crash course in prostate health started in November last year. He went into the emergency ward of a public hospital for anaemia on Friday, 27 November 2020, and came out with a catheter on Saturday 28 November 2020. The iron deficiency was treated there and then: he would be 88-years-old before the catheter was removed.

A private urologist had been treating my father for a prostate condition since 2015. In the past, that involved having a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). More recently it involved tablets and injections.

Prostate, sexual and reproductive problems for men increase with age.*

After waiting nine hours in emergency last November, my father was admitted and I went home.

At the hospital, the Greek interpreter told my father how a catheter would drain his bladder and help his urine retention problems. My father agreed to the medical device.

I picked him up from hospital, where I was told to change the catheter bag every five to seven days. I was given a complementary urine leg bag and a bigger overnight bag. I was shown how to change them. I was given the details of catheter urine bag suppliers. The hospital would organise a follow up appointment.

So, I changed the bag after five days. I used the complementary bag. It was simple. Everything worked well.

Twelve hours later at 5am, the bag began to leak. My sister investigated. My sister-in-law who worked in aged care investigated further. The conclusion was unanimous: the bag was leaking from everywhere. They called me at 7am and asked what I had done.

I rushed from my inner-city Richmond flat to my parents’ house in Oakleigh, south-east Melbourne. My father was sitting in his pyjamas and robe in the lounge room. At his feet was a blue bucket. The catheter bag was leaking into the bucket.

We went to my father’s GP who is of Greek background. There was a relieving GP, also of Hellenic background. He saw us first.

“I changed my father’s catheter bag, the smaller one that straps onto the leg, yesterday afternoon,” I said.

“It started leaking this morning.”

But the garbage bag wrapped around the leaking catheter bag got fuller and fuller. This was now a job for an expert. The GP got us an instant appointment with a urology nurse.

We visited the nurse, who calmly explained I inserted the bag incorrectly before fixing it and allowing me to take my father home. We sighed with relief.

“Τί κακό μας βρήκε;” my father wondered. I, too, wondered what bad luck had found us.

My father showered and dressed, but the urine bag was wet. He patted it with a towel, and patted it some more. He patted and patted, but it didn’t matter how much he patted; it was a faulty bag.

We drove back to the nurse. She inserted a new bag. I took my father home. I threw out the hospital-issued complementary bags and bought $200-worth of urine leg bags and bigger overnight bags. It was cheaper to buy in bulk.

I vowed never to change the urine bag again: I vowed to consult the experts. I rang the expert physician. He was fully booked and then some before Christmas, but he saw us anyway.

He examined my father, did a Trial of Void (ToV) to check his urine flow, changed the urine bag and recommended my father be put on the category 1 waiting list for another TURP.

So, the GPs kept changing my father’s catheter bag every four to five days. The second last change before the new year was on Christmas Eve and the relieving GP told us he could change it at his inner-city clinic that was still open. We went.

Then it was back to the hospital five days later, on Wednesday 30 December 2020, to do a ToV and remove the catheter.

I stayed to interpret.

READ MORE: Info blind spot for prostate cancer sufferers

My father failed the urine flow trial, but made a friend, Mr Dimitri, from nearby Clayton. The two were practically neighbours, and even looked like each other: slim and wearing tailored trousers with a sharp crease, V-neck jumper, sports jacket and polished, heeled leather shoes. The duo had Greek GPs with similar sounding surnames.

Initially they spoke to each other in the formal, old-fashioned Greek way: last name first, first name last, always in the plural.

“Από πιο μέρος της Ελλάδας είστε, αν επιτρέπεται;” Mr Dimitri asked.

“Σέρρες,” my father answered. “Και εσείς;”

“Koζάνη,” Mr Dimitri said of his town, 170km away from Serres in the west of the same north-eastern Greek province of Macedonia.

Then the pair drank their jugs of water and walked up and down the corridor holding arms as they waited for their test results.

As more men were admitted, I was moved into the waiting room a few metres away, but Mr Dimitri would come and call me if my father didn’t understand the nurses.

Hours passed. My father failed his second ToV. He left hospital with the catheter.

On to more tests. He had a cystoscopy on 20 January, 2021. There was an elderly ex-patriate American man waiting with him. Like Mr Dimitri, he was smartly dressed in tan-coloured pressed trousers, white shirt, a sports jacket and tan leather shoes. I explained to him what the nurse was saying until his brother-in-law came.

Last shot in the locker room. My father had his third ToV a week later, failed, and a specialist nurse showed him how to do intermittent self-catheterisation. But the sterilisation required in handling the single-use-only catheter was too hard, and the trial was abandoned.

My father got a urinary tract infection after that. He spent a few days in hospital in February, but was released two days before Victoria’s snap third lockdown, on 13 February.

It was now two-and-a-half months and my father still had a catheter. So I talked to my old school friend of Greek background who is a doctor.

“Do you know of anyone in the market for a secondhand catheter?” I asked him to which he laughed, assuring me the catheter would be removed. He told me to tell the hospital when they rang about the operation, that my father was having problems with the catheter. I did.

So, we waited for the TURP surgery and endured turd bags.

READ MORE: Builder-cum-restaurateur Harry Tsoukalas finds a new lease of life from offerings of the ancients

Have urine bag, will travel

Oh, hail almighty $10 urine bag! Please do not break today. But it did break that day – and every other day.

Every new bag the GP inserted broke. It broke on Monday, 22 February, Wednesday 24, Thursday 25 and Friday 26 February. On the third day of the trifecta we started to panic. It was my niece’s engagement the next day, on Saturday 27 February. The engagement had already been postponed last year because of lockdown, and narrowly missed getting postponed again with Victoria’s snap third lockdown.

The bag the GP inserted on Friday 26 February needed to last 36 hours. As a precaution, the Greek-Australian GP showed me how to change the leg urine bag.

I took photos of the stages. The GP gave me a sterilised clamp to take home if I needed to change the bag just before or during the engagement. “See one. Do one. Teach one,” the GP said.

That’s a traditional format for acquiring medical skills. It’s based on the the three-step process of visualise, perform and regurgitate. The GP said I had a talent, and thought I should become a nurse.

I thought I should pray. I drove past a closed Greek church that evening and did my cross. The pharmacist suggested I use surgical gloves for added protection. I bought the box.

“We’ve just got to make it to midnight on Saturday 27 February,” I told my father. “We’ve just got to make it to the end of your granddaughter’s engagement.”

Oh, hail almighty $10 urine bag! You did not break that day. In fact, the urine bag made it to the end of the engagement plus one day. Then it let rip.

The after-hours clinic GP said our bags were of poor quality. I told her we had just spent $200 buying 20 after being impressed with the first batch. She told me to get better bags, which I did, from another supplier. The new bags worked and there was peace, while I also held onto a piece of paper indicating that surgery in the public hospital was imminent.

My father had his TURP on 30 March and stayed in hospital for a few days. There were COVID-19 restrictions on visitor numbers so we children couldn’t always be with him. We wondered how he would communicate.

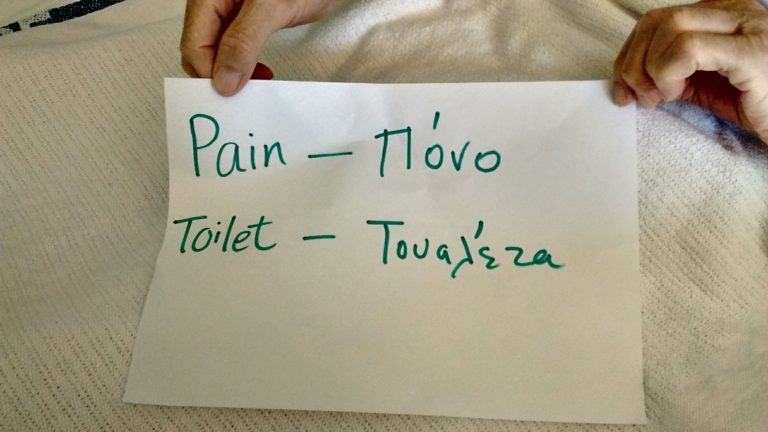

Easy. The hospital staff called me. They called the telephone interpreter service. They wrote on a piece of paper “Pain” on one line and “toilet” on the other.

I wrote the Greek words for each. My father then pointed to the relevant word to describe his condition. (See pic 1). It worked.

The physiotherapist called me too, stating she was having trouble communicating with my father.

“You speak Greek?” my father kept asking her.

The physiotherapist lamented she didn’t speak a second language and began examining my father.

She asked if his legs were weaker since the epidural or the same? My father said his legs were better. Then she looked at how well he used the walking frame, and also saw my father do his daily arm, back and leg exercises.

Finally, she wanted him to walk in the corridor with his walking stick to see how well he walked.

My father showed her how he used to kick the ball for his Greek village’s soccer team in Nea Kerdillia.

Even though there wasn’t anyone to interpret for him, my father seemed to manage. There was the 30-something young man in his ward who got on crutches to help him with his food.

I had brought Greek food for my father. I gave the ex-pat American also in the room some stewed vegetables with pork, the Greek cheese pie “τυρόπιτα”, tzatziki, bread and watermelon. The two ate. The two toasted each other with the tea in their plastic cups.

“Στην υγεια σου, and good health to you,” my father said.

“Cheers,” the ex-pat responded.

My father was on the mend, and his catheter was removed on 1 April: four months and four days after it was inserted. He was released from hospital on 3 April. I SMSed my old school friend, the doctor from a Greek background, to relay the news.

”Hopefully, things will continue to improve,” he wrote.

“And once everything has healed, he will be weeing like a 20-year-old.”

“I’ll take weeing like a 60-year-old ,” I replied. “Anything, but that catheter and those leg urine bags.”

*For further information on men’s health read the Australian Government’s, “National Men’s Health Strategy 2020-2030”, at www.health.gov.au.