Looking back through history at humanity’s response, it is clear that there is something disconcerting about animal-human hybrids. One need only look at literary representations such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and The Island of Doctor Moreau by HG Wells. This fear is often embedded in the view that these creatures are both unnatural and monstrous, and essentially, should not exist.

But as with anything taboo, whether we like to admit it or not, there is always a sense of intrigue, and Dr Evelyn Tsitas can certainly attest to that.

“The trouble with hybrids is that they disturb our moral compass, reminding us that we are animals, and animals are like us. When we look into its human eyes, we see ourselves looking back from the animal body we deny we inhabit,” she says.

This idea forms the basis of Dr Tsitas’ PhD, and after years of research has culminated into an impressive exhibition. My Monster: The Human-Animal Hybrid, currently on show at RMIT Gallery, features artists from around the world that bring her dissertation to life through imagery; each piece looking at different cycles of the human-animal hybrid, from how it is conceived in the human imagination, to how it appears on earth in a fictional setting.

“In Greek mythology it’s usually in the guise of a god who comes down in the form of an animal and seduces somebody, and then begets a hybrid creature like the Minotaur, and then that creature is usually alienated. It’s tragic,” she says.

“It has a very hard lifestyle; it’s neither animal nor human, and I think we all see that; we can understand inherently that metaphor of not fitting in, of being the outsider,” which Dr Tsitas can empathise with firsthand.

As the child of migrants, with Greek and Baltic German origins, while she says she was embraced by her Greek relatives, she acknowledges the unrelenting frustration brought on by not speaking the language. While close to her yiayia, she could never have a proper conversation with her, which was “very upsetting”.

“So I think inherently I felt something with the hybrid, I felt some sort of empathy with them; I understood that apartness,” she reveals.

It’s been an interesting road for Dr Tsitas, getting to this stage in her career.

The origins of her interest in hybrid forms and the dark prospect of what people could turn into if they did bad things, stems from childhood. Her pappou exposed her to Greek mythology, while her oma would read her the Grimm fairytales.

Her interest moved in a different direction after co-publishing Handle With Care, stories on the experience of high-risk pregnancy. Drawn towards ideas surrounding the medicalisation of reproduction, as a former journalist with a great love of words, she decided to pursue a Masters at RMIT, delving into how fiction, namely dystopian science fiction novels such as Blade Runner and The Handmaid’s Tale, deals with the subject matter.

Despite her focus being on creative writing, Dr Tsitas soon found herself being invited to present her findings at bioethics conferences, highlighting the interdisciplinary nature of her subject matter.

It was in 2008, at one such conference, that she first heard a paper presented on xenotransplantation – the act of animal parts being transplanted into humans – which she recalls as “the most amazing thing”.

What she heard that day would stay with her, and subconsciously, she started to draw from her visual arts background, giving way to visualisations of painter Peter Booth’s artworks that would become a turning point towards her PhD.

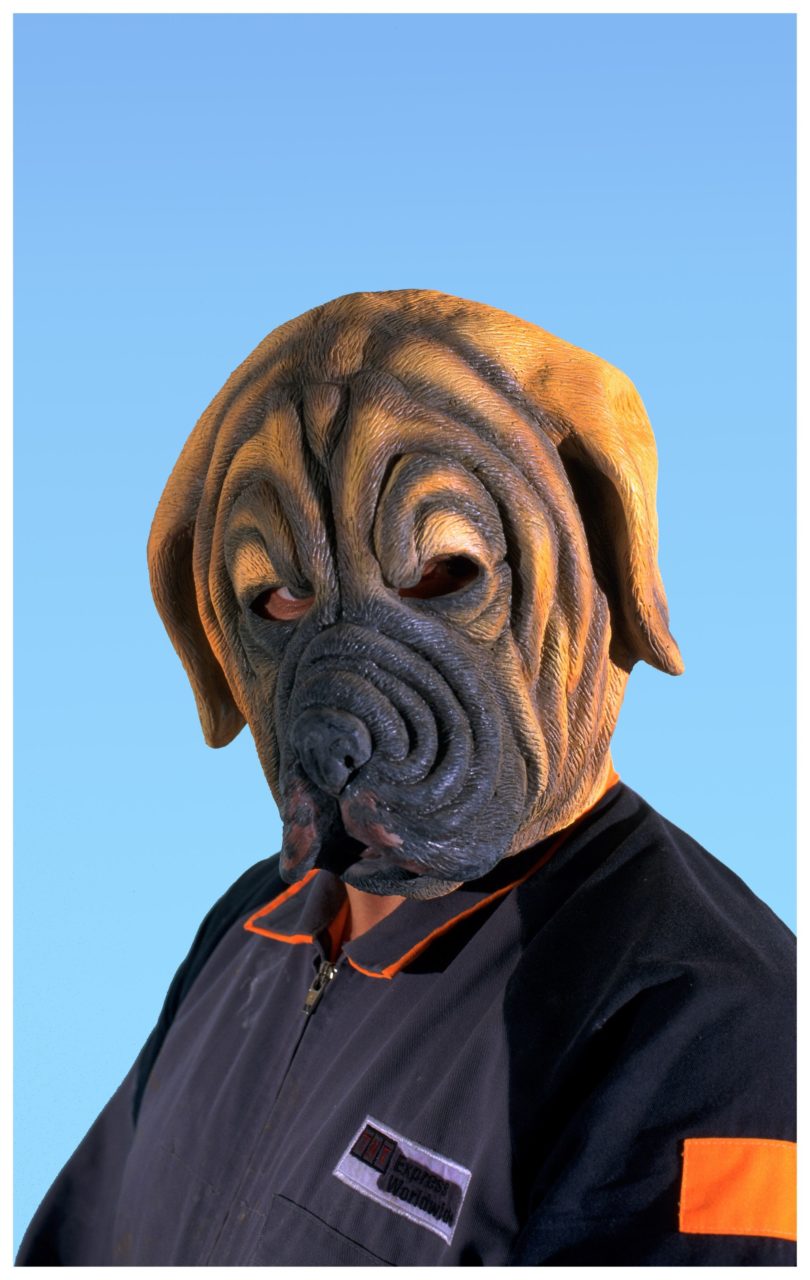

Some of the artworks featured as part of the exhibition: Ronnie van Hout, Sculpt d. Dog, 2001, print on archival museum rag paper. Image: Courtesy of the artist

Deborah Klein, Actinus Imperialis Beetle Woman, 2014, watercolour. Image: Courtesy of the artist

Sam Leach, Pedestal 2, 2018, oil on canvas. Image: Courtesy of the artist

Lisa Roet, Humanzee Part 2 from the 'When I laugh, he laughs with me' series, 2014, C-type photograph. Image: Courtesy of the artist, Hugo Michell Gallery, Adelaide and MARS Gallery, Windsor

While Dr Tsitas admits embarking on a PhD was never about putting an exhibition together, by the end, she says she basically had a whole portfolio of artists.

So when an opportunity arose earlier this year, thanks to acting director Helen Raymond, she says she jumped at the chance.

As the first exhibition Dr Tsitas has curated, so far she describes the experience as “exciting” and “seamless” thanks to support at the university. Having received a positive response with a line around the block on opening night, she already has a second exhibition lined up, which will look at the future of humanity in a different context but “equally as provocative” she assures.

While it is a thrilling experience to see her research come to life through imagery, she says it is the chance to engage a greater audience that is the most rewarding.

“One of the things we are now asked to look at is our research impact as academics; where is your research going, what does it mean? […] There’s only a certain amount of people that reaches,” she says.

“I used to write for the Herald Sun, so I know that feeling of reaching a large audience, and then to be able to do that with your research is incredibly satisfying because it means I’m not writing into a vacuum.”

But Dr Tsitas also acknowledges that timing plays a major role.

Given hybridity’s versatility as a metaphor for matters including discrimination based on race, gender, and ambiguities of sexuality, she says it’s as good a time as any to explore these issues.

“Ten years ago the idea of transgender and exploring whether kids in primary school are unsure of if they’re boy or girl – that was unheard of. But now it’s seeping into everyday conversation; mainstream magazines like The Women’s Weekly are discussing these in really calm ways,” she reflects.

“It seems to be definitely part of the zeitgeist, if I can use a German word; that sense of a spirit of the times, of understanding and accepting.”

While it is a highlight for the curator to see Peter Booth’s work featured in her exhibition given his influence on her work, she is proud to say that there are an overwhelming number of female artists being exhibited, admitting it was both “a conscious choice, and a choice embedded in the thematic aspects of the exhibition”.

Coming back to the origins of her interest in artificial reproduction and biotechnology, some of the works explore what it means to be a mother, and a woman in this age, and how those boundaries can be blurred, citing an image of a woman breastfeeding a dog.

Living in a world that celebrates perfection, and elevates ‘natural living’ to a cult trend only few can afford, there’s no denying we have moved away from our roots, and our understanding of ourselves as interconnected with nature. In society, debates arise surrounding whether women should breastfeed in public – a very natural, animalistic act – and women with body hair has also become taboo.

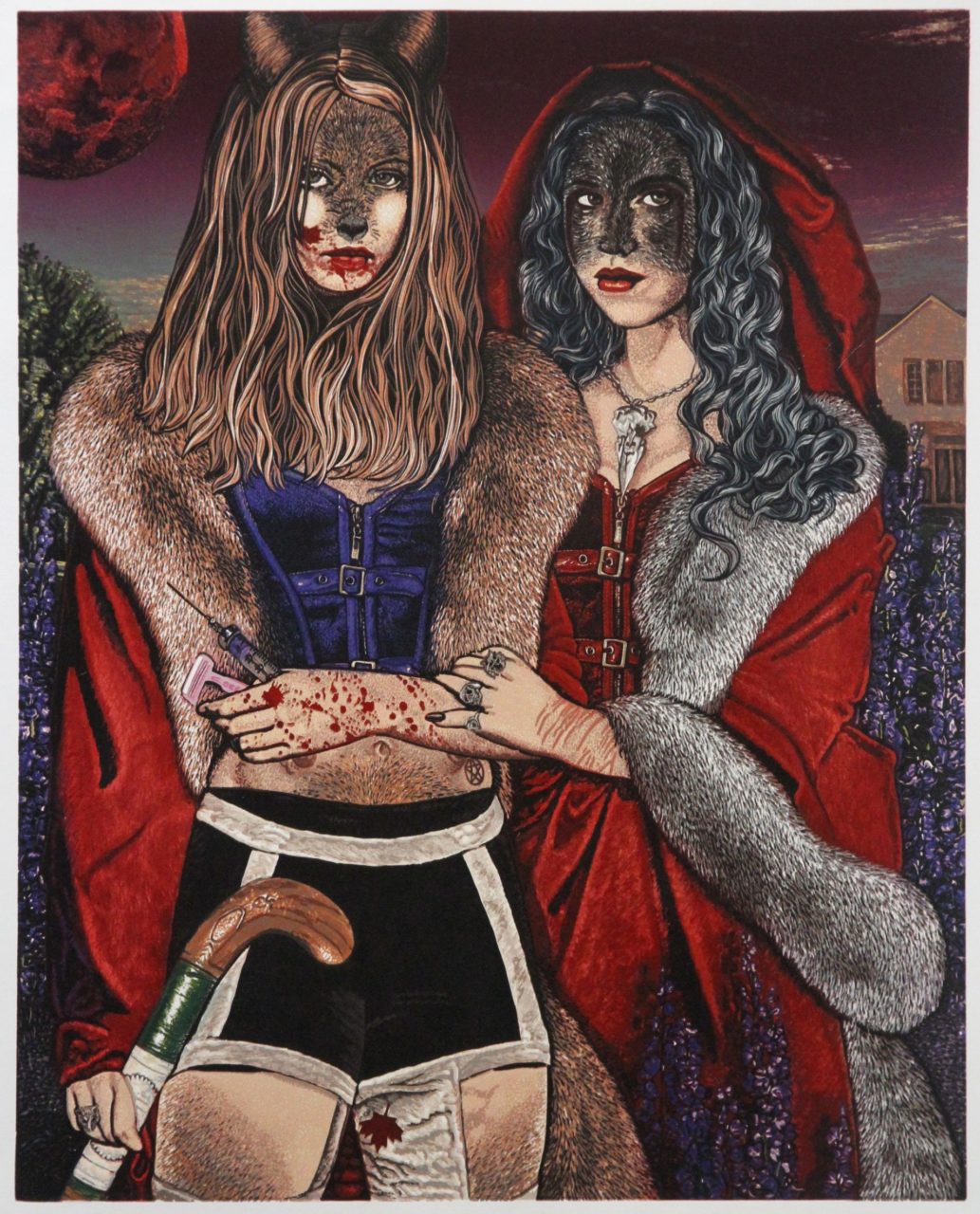

“I was very interested in showing as many representations as possible of women with hair on them, because there seems to be a whole generation of people who don’t understand that women have body hair, which I find bizarre!

“So I really wanted to turn that around and have huge pictures of women with hair; if they’re werewolves, if they’re naked but hairy, because I wanted people to see that ‘yes, we are that person, we are that animal’.”

This then lends itself to animal rights. By humans seeing themselves within these hybrid forms, Dr Tsitas says it can be disturbing to think about how we use animals.

“We skin animals, we wear them, we eat them, we use them in medicine, all of these things. If you think of how close we are to animals, for instance primates – we share up to 97 per cent of our DNA with orangutans – that is disturbing.”

Jazmina Cininas, Blood Sisters, 2016, linocut reduction. Image: Courtesy of the artist

Rona Green, Dusty Rhodes, 2011, hand-coloured linocut. Image: Courtesy of the artist and Australian Galleries

Barthi Kher, Angel from the series 'Hybrids', 2004. Image: Courtesy of the artist

While Dr Tsitas grew up familiar with hybridity through her exposure to mythology and folklore, she understands that many people can become uncomfortable, even squeamish, around artworks depicting human-animal hybrids. But in the curator’s opinion, any reaction, whether positive or negative, is better than shying away, and avoiding the issues they represent.

“If you think about it, why don’t you get upset about what scientists are doing, which is actually at the moment creating human-animal embryos to experiment on in stem cell research and it’s on our doorstep?

“Australia is one of the countries creating transgenic pigs. So they’re modifying pigs genetically to have human cells so we can take their organs and transplant them into humans without fear of organ rejection,” she states, bringing the curator full circle and putting her exhibition smack bang in the middle of the provocative debate surrounding ethical boundaries.

“We can do something with science, but what does it mean for what we create, and what we destroy at the same time?”

My Monster: The Human-Animal Hybrid draws together an array of important philosophical and ethical ideas in a strong visual and cohesive way that covers everything from race and gender, to the environment.

When you first walk in, you will be greeted by a sculpture of a deer with a human face, a creation by American artist Kate Clark, galloping above ground, over an expanse of fake grass.

And if Dr Tsitas wants to ask anything of her audience, it’s that they don’t look away.

“The animal-hybrid provides, if you like, a visual face, a human face, an empathetic face to these issues; it’s not just pure science. This is embedded in asking people to think. We all have to confront these issues, and really think about it, and look at it in the face.”

Catch ‘My Monster: The Human-Animal Hybrid’ exhibition at RMIT Gallery (344 Swanston Street, Melbourne, VIC). Now on show until 18 August 2018. For more information, click here.

Please note: Some parts of the exhibition contain works that contain adult themes, which some visitors may find confronting. Adults may wish to view the space first before accompanying children or students.