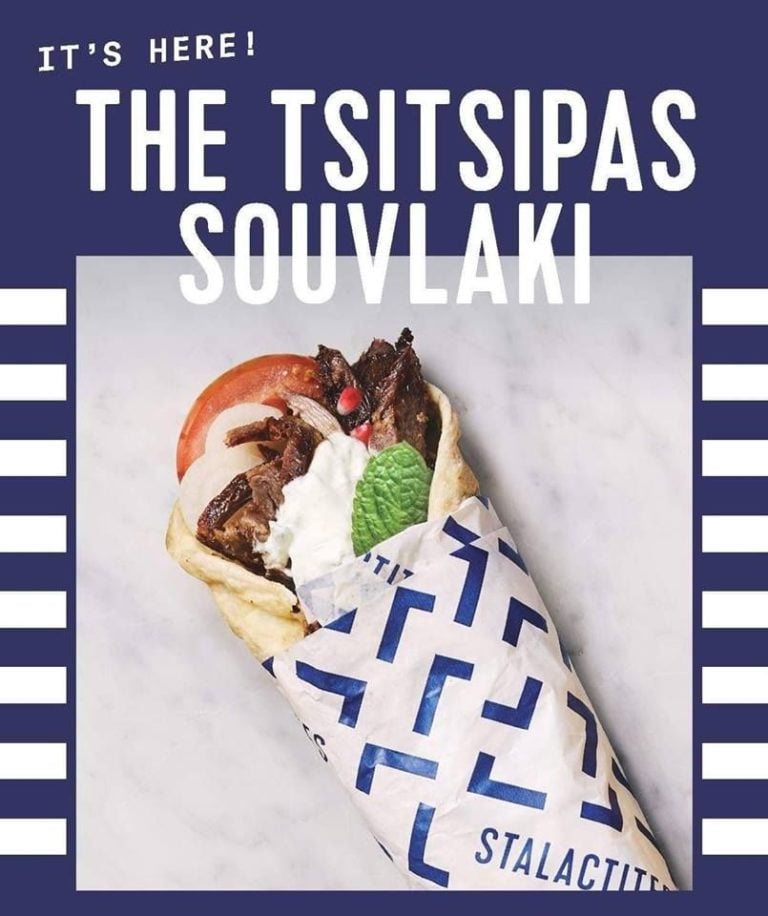

Lamb gyros, tomato, onion, tzatziki, hot chips – so far, you have the ingredients of your basic Greek souvlaki (let’s leave aside the debate of pork over lamb, for the moment); add feta cheese, mint, chili and pomegranate seeds to the mix and you have the ‘Tsitsipas’ souvlaki, launched by Melbourne’s Greek staple, the Stalactites restaurant, to celebrate Stefanos Tsitsipas’ monumental trajectory in this year’s Australian Open tournament.

Yes, Tsitsipas’ meteoric rise to the top was forcefully and abruptly cut short by Rafael Nadal’s bullish game, but this does not diminish at all the 20-year-old tennis star’s success – nor can it take away the joy and moral boost he gave to Greeks all over the world.

The Greek tennis star is definitely here to stay – his namesake ‘souva’, on the other hand not so much, its survival pending on the willingness of meateaters to have pomegranate and mint with their lamb-and-tzatziki.

As for our collective source of moral boost, this now depends on whether Yorgos Lanthimos will manage to leave the Los Angeles Kodak Theatre with an oscar for Best Director on 24 February, one of the astounding ten nominations his sardonic period drama The Favourite has accumulated. It is a remarkable achievement for a film director who has been consistently and continuously making a name for himself in the world of cinema, moving on from the international film festival circuit to the cinematic mainstream and being acknowledged as one of the most uncompromising visionary auteurs of our times.

So far, no culinary establishment has moved forward to present a delicacy named after Lanthimos – Lobster Pizza, anyone? Sacred Deer Burger? No? OK – but there is still time until 24 February, when the winners of the 91st Academy Awards will be announced.

And it is safe to guess that Greek film buffs all over the world will be watching the ceremony with equal passion as those who were camping outside Rod Laver arena, wrapped in blue-and-white flags, chanting slogans in support of Tsitsipas and – in a demonstration of the immortal spirit of Hellenic hooliganism – spewing insults against our national enemies. Whatever – Greek boys will be Greek boys, and our Greek boys definitely need to let off some steam, after having their spirits crushed by crisis, austerity – not to mention the ‘Macedonian’ issue.

It was a happy coincidence for Greeks that Lanthimos’ nomination was announced on a week that we were all flooded with enthusiasm over Tsitsipas’ victories. It was a much needed breath of fresh air, after what seems like almost a decade of gloom.

“This is the face of Greece that resists,” online commentators stated in unison, raving over the combined success of Lanthimos and Tsitsipas, presenting them as shining examples of the undying Greek spirit, which can always overcome adversity and blossom under any circumstances.

Read through the volumes of digital literature written these past few days in the Greek publich sphere and you may start listening the echo of the old marching song: “Greece never dies/ She is not intimidated by any fear/ She only rests for a little while/ And goes back on her track towards Glory.”

For a brief moment, it was as though a new Greek revolution has begun, led by a tennis player and an obscure film director. Our chests were bursting with national pride – and then some critics approached holding pins. “Not so fast,” they said, gleefully watching our chests deflating. Their argument is solid. None of us can claim any stakes at Tsitsipas and Lanthimos’ achievements. Their success has nothing to do with being Greek – if anything, they both succeeded despite their nationality. Anyone following Tsitsipas’ story knows that his success is a result of personal work and dedication, fuelled by solitary training and passion and funded by his family. The Greek state has infamously been very reluctant to allocate resources to the national tennis federation.

As for Lanthimos, his trademark style – that spearheaded the ‘Greek Weird Wave’ movement – has received so much criticism in Greece, and his festival success has been met with such disbelief (if not outright hostility), that he specifically decided to leave Greece and its version of the ‘tall poppy syndrome’ to pursue a career in London. The Favourite is an Irish-British-American production that happens to be directed by a Greek.

If it wins an Oscar – or ten – this does not give anyone permission to wave the blue-and-white flag.

From this point of view, Lanthimos and Tsitsipas are symbols of what Greece isn’t: a country of meritocracy, where talent and hard work is rewarded and where anyone can follow their dream.

From this point of view, the success of Lanthimos and Tsitsipas should make us feel national shame, not pride.

Of course, national pride is a very tricky concept in itself – it means feeling proud of something that is beyond your control, if not purely coincidental. We are all born in a specific territory, by specific parents and this chance occurrence defines and affects our lives – but we can choose not to let it be a burden for us.

Greeks have been burdened by their national identity, groomed through decades of ideological manipulation through the education system, to feel proud for the achievements of people that lived and died ages ago – from Homer and Pericles and Leonidas to the warriors of the Revolution against the Ottoman Empire. It is one thing to be inspired by people, actions and ideals and a completely different thing to feel proud of them, as if it’s your own achievement. The former acts as motivation, the second as entitlement.

Tsitsipas and Lanthimos are motivated, not entitled.

Still, there is something very mean-spirited and skimpy in denying people the right to feel enthusiastic and joyous about Tsitsipas and Lanthimos.

Yes, their success is a result of individual effort, not a collective one, but if we want to manage to beat the culture that prevents others from following the same path, we need to back down and not attack their enthusiasm with cynicism.

It is the only way to leave room for the next aspiring tennis star to breath, and for the next filmmaker to create the next Greek [something]-wave. It may happen. It may not.

But there is no harm in being generous about our community’s feeling. And no harm in expressing gratitude towards those who inspire us and bring us joy.

Even if this gratitude comes in a form of a weird souvlaki.