“…when Antony and Dolabella were accused to him of plotting revolution, Caesar said: ‘I am not much in fear of these fat, long-haired fellows, but rather of those pale, thin ones,’ meaning Brutus and Cassius.” – Plutarch The Parallel Lives

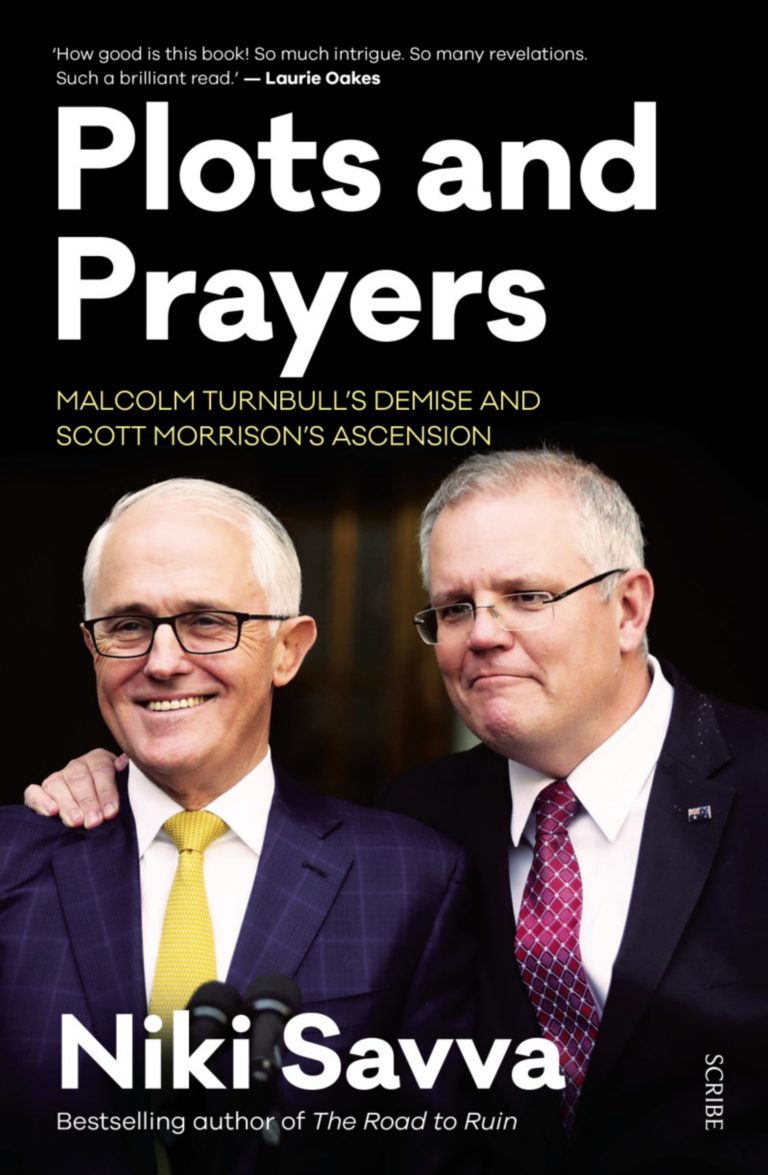

Plots and Prayers by Niki Savva is a fast-paced hard-boiled account of the machinations leading to the fall of Malcolm Turnbull and the instalment of Scott Morrison as Australia’s seventh Prime Minister in 11 years. An event that according to Savva, ‘cemented Australia’s humiliating status as the Italy of the Pacific’.

Savva, journalist, author of books on Australian politics, and a regular on the ABC’s Insiders had privileged access. She was after all a former adviser to treasurer Peter Costello.

She interviewed everyone, almost.

“On the Monday I asked Mathias Cormann if he was going to stick with Turnbull and he said ‘until bitter end’ Cormann kept his council after that, he never got back to me,” Savva says.

Cormann turns to wood and Morrison becomes the redeemer

Finance Minister and Government leader in the Senate Mathias Cormann was the last buttress holding up Turnbull’s prime ministership. Peter Dutton needed Cormann, who would bring 10 votes over.

In his last appearance standing next to Turnbull, Savva describes Cormann as a ‘plank of wood’ pledging his loyalty. Hours later Cormann shifted to Dutton. Cormann is presented as the real Ephialtes. Bishop had warned Turnbull never to trust Cormann but he didn’t listen.

Morrison made it clear he would not take on Turnbull. ‘Howard never called a spill’ he counselled Turnbull. Morrison was ready though to present himself as the redeemer and save the Coalition from the dreadful prospect of Dutton as prime minister.

Morrison supported Turnbull as his ‘lieutenants’ began populating their databases and were counting numbers.

The Dutton camp was messy, a boys’ own adventure that believed their own puffery. Once Dutton began his move says Savva, “Morrison’s men sensed Turnbull was finished so they planned ahead”.

Those who pray together play together

Morrison’s numbers men, Stuart Robert and Steve Irons, shared an apartment with him.

“Morrison must have known,” Savva says in deadpan certainty.

Robert, Irons and Alex Hawke, a key strategist, all belonged to Morrison’s weekly prayer group. God whispered their destiny in their ears.

Morrison may never have endorsed a move against Turnbull but he did not have to. “His lieutenants did not need his authority,” according to Savva.

Morrison rejects those assertions in the book. He was ready to step into the breach and took moderates and conservatives with him to become prime minister.

Ken Wyatt, who was ready to resign if Dutton became prime minister, counselled Julie Bishop not to run against Dutton. She did not have the numbers.

Morrison was seen as the only real defence to Dutton. Morrison’s victory had another desired effect; it “critically wounded Cormann and Dutton.” Even if Turnbull had won the second count, Dutton would not stop challenging him according to Savva.

Plots and Prayers is a mandala of calls at all hours of the night, WhatsApp messages, monkey-pod meetings, conspiratorial dinners, bullying and intimidation (mainly of women peers), surprise meetings with surprise characters, meltdowns and betrayal.

‘Turnbull’s denouement remains a sorry saga of betrayal, conspiracy, miscalculation, hubris, and conflicting loyalties and emotions.’

The murder of crows

The 2016 campaign was a disaster for the Coalition. It lost 14 seats. For Savva, Turnbull was a bad campaigner; the party had limited campaign funds (Turnbull had to inject his own money); was beset by poor candidate choices; and a late pick up of Labor’s Mediscare lies. The dismal outcome, a one-seat majority government damaged Turnbull’s authority. He became reliant on Cormann and Dutton as his key ‘bridges to the right’.

“Turnbull did what he could to keep the conservatives in the tent and in doing so, abandoned moderate friends,” says Savva.

“The idea being, you keep your friends close and enemies closer, only Malcolm forgot the former,” she adds wryly.

The right never forgave Turnbull for Marriage Equality. Labor and the Greens wanted Turnbull to fail because they felt they owned the reform. Savva declares, “Turnbull will always be remembered for this great reform.”

Simon Birmingham convinced Cabinet to reveal the Labor seats that recorded a higher no vote in the poll. Blaxland held by Labor’s Jason Clare scored the highest no vote; a whopping 73.9 per cent opposed marriage equality. Birmingham’s strategy exposed those Labor members fastened to their party’s line who voted against their own constituents’ wishes.

Australians voted yes and Abbott and his ‘surrogates’ began a guerrilla campaign against Turnbull.

“If the right, Abbott and his surrogates had let Turnbull do his job he could win, but some of the wounds were self-inflicted,” adds Savva.

We were disappointed with Turnbull. “Many expected him to be what he was – yet he was a leader of very disparate party,” she laments.

Abbott’s gang, the likes of Craig Kelly, George Christensen and Tina McQueen viewed Turnbull as Labo-lite. McQueen had a special ‘reputation as a Turnbull hater and unabashed Abbott fan’.

The problem was that “the right had kept Turnbull on a tight leash” Savva points out.

“It would have been better if Malcolm on occasion did override them and make decisions,” she says.

Turnbull reinstated proper cabinet process after Abbott’s shambolic management but also became its victim. Cabinet meetings often became talk fests and decisions were deferred.

Dutton began to see no future with Turnbull. He convinced himself he could do better as prime minister but needed Cormann. In the meantime, Morrison’s lieutenants planned.

Turnbull would not consider Cormann a traitor, regardless of what those who cared for him said. When Turnbull finally accepted Cormann’s deceit, he sacrificed himself to block Dutton’s ascendancy.

“Turnbull decided not to die on his knees and to stop Dutton from the prime ministership,” says Savva.

Labor brought down by hubris

Labor saw itself as a government in waiting. At the Press Club, as Shorten prepared to speak, Labor advisers suggested that journalists had to begin getting used to ‘calling him prime minister’ Savva relays. The media had written off the Coalition.

“But Morrison loves campaigning, and he flies solo,” says Savva.

Bob Hawke’s death also worked against Shorten.

“The more people realised Shorten wasn’t like Hawke, the warier they became,” Savva adds.

Morrison was “driven by a deep belief that he could repeat Keating’s feat in 1993 and win the unwinnable election”. Shorten was for Morrison, Keating’s Hewson.

For Savva the ALP suffered a “deadly combination of being lead by a deeply unpopular leader, who was trying to sell deeply unpopular policies.”

“I organised a plumber, a young guy 23 years old for my mother’s house, he had bought his first house and was about to buy another, Labor had lost complete touch with their own people” she illustrates the distance between Labor and its natural constituency.

For Savva Labor’s arrogance was in full view, “when Senator Penny Wong refused to shake Birmingham’s hand.”

Labor’s sounded and felt like it was run by a university students’ union.

Who’s wagging the dog?

Prime Minister Morrison enjoys the full confidence of the Coalition. “He beat Labor single-handed,” says Savva. Morrison the “pragmatic conservative is not economically conservative, is also constrained by the right,” warns Savva.

“As soon as he gave Ken Wyatt [Minister for Indigenous Australians], the okay to go out and begin talking about the constitutional recognition of First Nations people the right began to move, Craig Kelly was on Sky News rejecting creating fear about a third chamber.”

Savva is mildly optimistic. If ScoMo can “shift the Liberals to the centres away from the right and learn to consult his peers” he may succeed. If Anthony Albanese can wrench Labor away from disastrous identity politics and class warfare, they still may be a party to be reckoned with in the next election. She points to how Howard “wiped the floor with Latham in 2004 only to lose to Rudd in 2007”.

Plots and Prayers has secured Niki Savva’s place as a modern Australian storyteller, a wry bard relaying the cruel pantomime that politics can be.