For many in the community, Effy Alexakis’ name is interwoven with a rare documentation of the Hellenic presence in the Antipodes.

Understandably so, as the visual project ‘Greek Australians: In their own image’ she co-created with historian Leonard Janiszewski has been widely promoted in recent years in exhibitions presenting segments of their ongoing research in Australia and abroad.

Last week, the announcement of an award turned the spotlight on the photographer once again.

The inaugural O KOSMOS – Insight Series, a tribute to Alexakis’ work, was the winning nominee at NSW Premier’s Multicultural Communications Awards for the ‘Publication of the Year’ category.

The magazine’s first edition titled ‘Effy Alexakis: a Celebration of her work’, was published in March 2020, by the Sydney-based Greek newspaper, featuring pieces from more than 10 contributors analysing her trajectory.

Photo: Facebook/Yiannis Dramitinos

Photo: Facebook/O Kosmos

” I valued the magazine before it won a prize, I appreciate that it has been recognised. Am very proud,” Ms Alexakis said in a statement, thanking everyone involved in putting the publication together, as well as the very people who shared their stories with her throughout the years.

READ MORE: Aussie Greek speakers: Hellenic language, a rich vein of knowledge for Australians

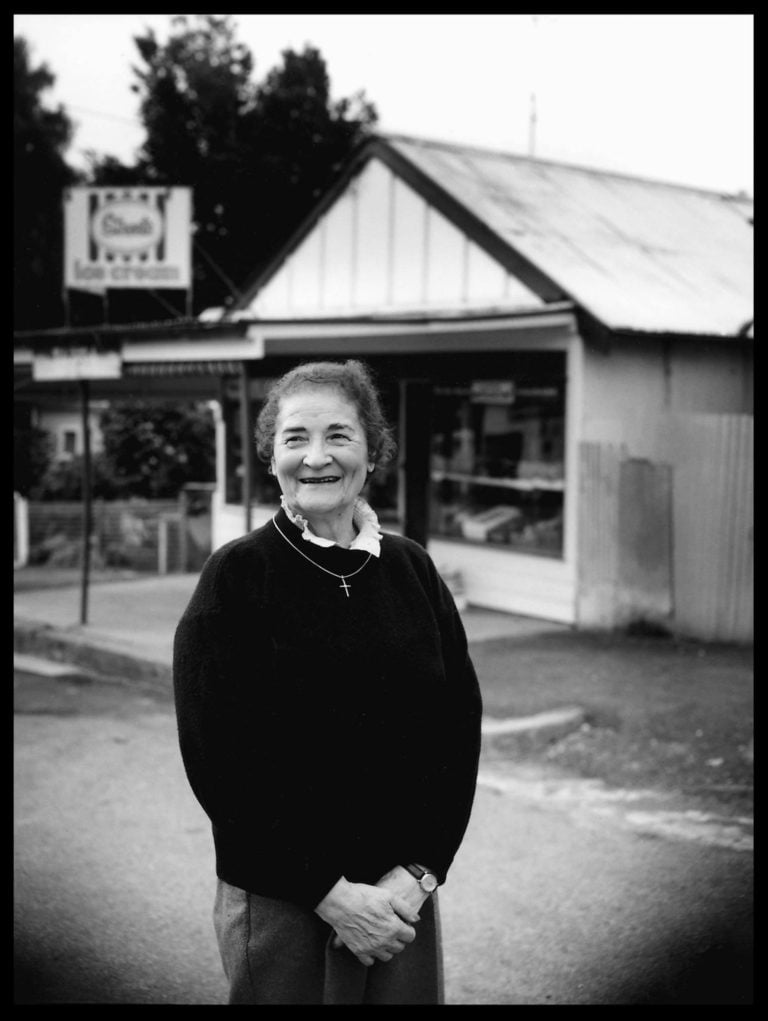

Alexakis’s and Janiszewski’s undertakings recording more than 2000 interviews of Greek Australians’ lived experiences, has been hailed as unique in its kind both here and overseas.

The project’s beginnings are highlighted in their recent interview to journalist and student of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Hande Yetkin, of which edited parts are presented below:

Ε.Α: My parents came in the 1950s and while we were growing up, they had the idea of making some money and then going back (like many returned Greek-Australians did). And I think that’s typical of the migrant story here. When we interview people, they always say that they were planning to come and to work for a few years and then go back. So when my father died quite young – he was 55, I think it cemented the idea that we would not go back and we were Australian. Growing up, we were always told ‘you are Greek’. It was really hard to live as a Greek in a country like Australia, where you wanted to fit in, to belong. For my mother’s generation, as a first generation, she didn’t belong to Greece anymore, and never belonged here either.

Leonard was studying an MA. He was studying the gold rush period in Australia and he told me that he found a lot of Greek names – Greeks that came out to Australia from the 1850s, in search of gold. After my father died, I seriously started focussing on documenting Greeks generally. Combining Leonard’s interest in history and my interest in photography, we travelled around the country in 1987 and 1988, which is the year that Australia celebrated its bicentenary. We met a lot of interesting people, some were searching their family roots. We found quite a few people that were connected to the early gold miners, some fourth and fifth generation Greek-Australians. We interviewed them about their Hellenic heritage and what they knew about their forebears. We called the project ‘In Their Own Image’ because we use personal photos of Greek-Australians which I take, as well as quoting them in their own words, their voices. This project is ongoing.

READ MORE: More Greek than the Greeks

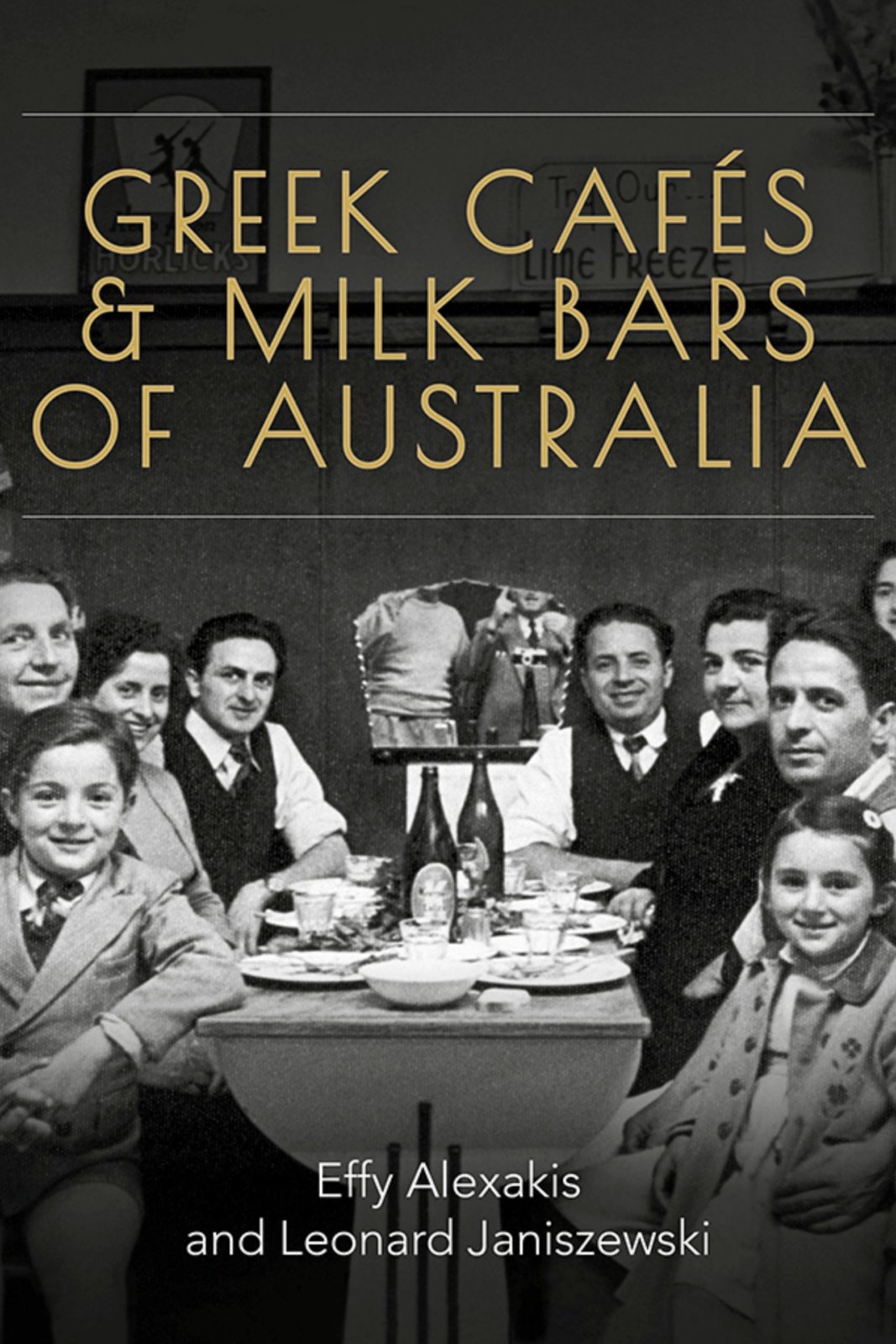

Of the duo’s most renowned research outputs is the book “Greek Cafes & Milk Bars of Australia”. It is considered a landmark publication for evidencing the Greek inspiration behind the first milk bar Down Under, as well as the intersection of British and American culture that gave rise to its humble beginnings.

Interestingly, as Ms Alexakis reveals, they had deliberately chosen to delay its publication, in accordance with an important premise informing their work: breaking down existing stereotypes for Greeks.

“When Greeks were depicted here in the media in Australia it was always what I called the folkloric stereotype[…],” she says, elaborating more on the issue as follows.

Ε.Α: There were thousands of these Greek-run cafes. We did not want to do the cafes and milk bars as our first book because we felt that it was promoting a stereotype – we didn’t want to promote the Greeks as simply cafe owners. We wanted to show that they were involved in Australian society in a plethora of occupations such as academics, doctors, creative arts, miners or politicians. If we had published this book first, it would have reinforced that stereotype. Besides, it has taken many years of research to create the book, we had to physically collect all the photographs and stories from around the country as

well as stories from within Greece and America.

Joining the interview, Mr Janiszewski goes on to highlight the lack of historical accounts focusing on “the diversity of Australia’s ethnic origins”, partly due to an absence of “archives that have emphasis on collecting materials from non-English sources.”

READ MORE: Taxed twice: Greek Australians aren’t just bicultural, they’re also double taxed

And the conversation flows from there:

L.J: […]The archives are culturally myopic. Historians only read in English from English language materials. So, as a result, what kind of a history can they develop? A British-Australian history. What we were doing was to collect materials with this particular group, meaning the Greeks, to show their history and how it affected Australia, because the culture we have here is not simply British or American. There is a variety, yet the focus is still on British Australia. We are collecting an archive and putting their voices on paper, creating exhibitions, films and so on. That will be carried on. We had to create our own archive by traveling around Australia as well as other areas in terms of a Greek Australian presence, but our materials were not only from Australia.

E.A.: We have been doing this since the early 1980s.

L.N.: We were young once!

E.A.: We were young once (laughing). We really enjoy this project. We get in the car, drive somewhere, knock on someone’s door and ask to interview. Leonard’s recorder is set up and we ask questions. I take photos and copy their early images. Then, we go to the next one. It has become very addictive.

L.N.: Demographic changes have occurred rapidly. We have tried to keep up with these rapid changes. We also found Greeks in unexpected places while they were doing unexpected things. We got so much material that we did not have time to fully analyze and appreciate it. We question things. We compared the negatives and positives, the whites and greys. So, it was not simply a celebratory history.

E.A.: We are still based at the university. They do not pay for us to do this, we do this project because we want to do it, because it is important. We also want ownership of it, so that we can develop it into a variety of other creative outputs – exhibitions, books, talks, films, essays etc.

READ MORE: A study of the iconic Greek cafe and milk bar [PHOTOS]

L.N.: Until, of course, we come to a point where we can longer be able to do that. But we have to keep it all together, because it covers a huge global geography. The synergies between all the materials will not work if we break it up.

E.A.: We started having exhibitions all around the country. We wanted to spread it out across the nation to get diverse opinions and have Greeks representing different regions. People would come to us with new stories, new photos, new insights. We have a huge archive.

L.N.: Even today, for instance, we are working on a small biography of a family that we interviewed in 1987. It suddenly became apparent that there were connections with other families and stories in a way that we hadn’t realized previously. We are still learning from the research archive we have[…] Historians in this country are looking at written documents. They use the images only as adjuncts, but photographs are real documents and can give you insights that the written material cannot[…]

*Edited extracts have been published with permission from the interview conducted by Athens-based reporter, Hande Yetkin for the newspaper Atina Haber.