When we commemorate Ohi Day we honour the resistance of the Greek people throughout the Second World War and the Allied forces who supported them, including those from Australia. These forces include hundreds of nurses from Australia, New Zealand and Britain. This is the story of one of those nurses, a British nurse of Greek heritage, who served as a military nurse from the outbreak of the war in 1940 and through the Greek campaign of 1941. She would be the only nurse to remain on duty during the battle of Crete in May 1941. Her name was Joanna Stavridi.

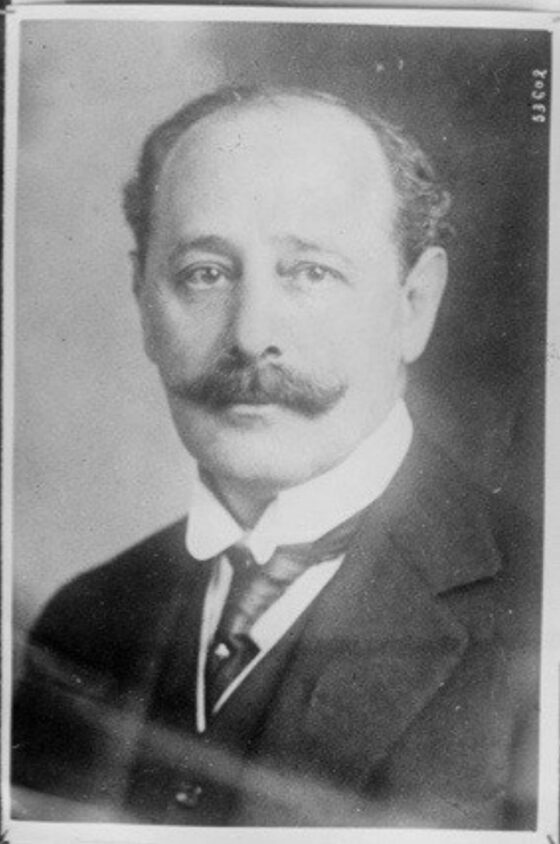

Joanna was born on 21 September 1903 in London, the daughter of John and Anna Stavridi. The Stavridi family came from Ermopouli (then known as Syra), where her father was born in 1867. John was a very influential figure, a former journalist turned diplomat, wealthy banker and financier, who had moved to London with his parents before the turn of the century. It should not surprise us that he came from this lovely island in the Cyclades. Visiting their today one might be surprised to realise that it was once Greece’s major port and trading centre.

Joanna’s father’s new roots in London did not diminish his loyalty to the land of his birth, serving as its Consul General almost continuously between 1903 to 1920. A friend of both Eleftherios Venizelos and Lloyd George, he played a key role as a diplomatic go-between, especially during the years leading up to, during and after the end of the First World War. After the war John was knighted by the British Government and would serve as Chairman of the British-owned Ionian Bank until his death in 1948.

There are indications that Joanna spent some of her early years growing up in Greece. Describing herself as “an ardent feminist”, Joanna was keen to play an active part in the war effort when war broke out in 1939. She soon began her nursing training with the Red Cross, serving at a First Aid Post in London. Fate would draw her to Greece, initially to care for her ailing sister in Athens. With the Italian invasion in 1940, Joanna joined the Greek red Cross, completing her nursing training and was soon posted to an ambulance train tending and transporting the wounded from the Albanian front.

Following the German invasion in early April, Joanna and her sister managed to gain passage to Crete aboard a yacht, joining a party of medical staff led by British Colonel Hamilton-Fairley. The journey would be dramatic, the yacht bombed and eventually destroyed, with many crew members killed and six badly injured. Marooned on the island of Kimolos, they had to wait to be picked up by another vessel and eventually arrived at Chania, the whole journey taking ten days. Throughout the ordeal Joanna would care for the six wounded men.

While other Allied nurses who had arrived there were evacuated to Egypt prior to the German invasion, on 14 May Joanna volunteered to remain on Crete, serving as matron and theatre nurse at the 7th British General Hospital, a large, tented field hospital of some 600 beds. Joanna was now the only Allied nurse on Crete. She would be noticed by patients, in her distinctive uniform of army battle dress and nurses cap. It was here that the wounded gave Joanna her epithet as “the Florence Nightingale of Crete.”

The hospital was set up near the coast in the open to the west of Chania, on a “three fingered” promontory. With the beginning of the German invasion, the hospital would remain working as the battle raged around them, shells arching overhead. One account tells of fully armed German soldiers charging into the hospital shouting orders at the Allied medical personnel only to dart off back into the battle, of German medical staff joining the Allied staff intending to the wounded of both sides and Allied ambulances driving through German lines carrying Allied and German wounded to the hospital. On one occasion the hospital was overrun, the staff and patients captured, only to be saved by the counterattack by a company of the New Zealand 18th Battalion.

Despite its Red Cross markings, the hospital was bombed, and machine gunned, medical officers killed, others wounded and much of their supplies destroyed. The Australian war correspondent John Hetherington who came to Greece during the campaign would write of this air attack in his book on the battle of Crete, Airborne Invasion, telling of the machine gun bullets tearing through the hospital tents.

Fortunately, the area contained ready-made bomb shelters in the form of caves along the nearby rocky coast. And so, during the night Joanna and the other staff moved the hospital and its patients to these caves. While conditions in the caves were not ideal – its previous inhabitants being goats and its floor uneven – the staff soon organized the hospital, with cooking areas, stretcher beds, hurricane lamp lighting and an operating theatre on stone slabs near the entrance. This would now be known as the “cave hospital”.

READ MORE: Greek Shipping: An important global actor in line with the Greek maritime spirit

The British official history reports that Joanna and the hospital treated an estimated 500 wounded patients as the battle raged overhead. Running out of food and supplies, Joanna is said to have successfully used a captured German flag to deceive the Germans to drop much needed food and supplies to the hospital.

The German capture of the Maleme airfield and their advance forced the Allied decision to retreat and with it the hospital and its patients who could be moved. And so it was that on 25 May, Joanna made the decision to stay and tend to those patients who were too ill to be moved, a decision that would lead to her eventual capture by the Germans a day or so later. The Germans could scarcely believe their eyes that a woman had served there through the battle. Now wearing her Greek Red Cross nursing uniform, Joanna continued to treat the wounded at the hospital until she was transported to Athens and released to continue working as a nurse in an Athens hospital.

The story of her brave service soon spread throughout the Allied world. No doubt her caring for Australian and other Allied soldiers in Crete touched a nerve in far off Australia after the fall of the Island and the capture of many Australia soldiers. The Australian press would print many accounts of her ordeal, serializing her story across Australia. It would be reported in the dailies of the big cities and the newspapers of Australia’s country towns and regions, carrying Joanna’s story to Wagga Wagga, the Riverina, Horsham and beyond, the home of many of Australia’s diggers who had served in Greece. Melbourne’s Age newspaper described her as “a very great and a very brave woman.” Wagga Wagga’s Daily Advertiser wrote that “all with whom [Joanna] came in contact could not speak too highly of her supreme courage, humour and efficiency” and Sydney’s World News headlined their account simply “a great woman.”

READ MORE: German Foreign Ministry rejects WWII reparations for Greece

Her story would also be captured in a visual story or comic book dedicated to her part in the battle of Crete created in the United State during the war to inspire the public in their own resistance to the Axis threat. This beautiful little comic book – featuring the story of the “cave nurse” – survives to this day in collections across the world, a treasured visual memory of Joanna.

The British Colonel Hamilton Fairley of the Royal Army Medical who had helped her escape from mainland Greece, wrote of Joanna as one of the most valiant he had encountered, adding “she was as tough as any man and as tireless as the fittest of them. Utterly fearless.” The writer and philhellene Dilys Powell wrote in 1941 of Joanna as a symbol of Greece’s resistance “a solitary woman, after the deliberate destruction by bombing of the hospital at Maleme [who] spent the last week nursing the wounded in caves by the sea.” By December 1941 Joanna’s service saw her awarded the Hellenic Red Cross and the Distinguished War Certificate by the Greek Red Cross and British Red Cross respectively.

When she returned to England after the liberation of Greece, Joanna continued to advocate for Greece. In response to Winston Churchill’s description in 1944 of EAM as “a gang of bandits”, Sydney’s Tribune quoted Joanna as having risen to EAM’s defence, pointing to the support shown by the Greek resistance to Allied soldiers on the run, of the poor people of Greece caring for Allied soldiers, in the face of famine and enemy retribution, helping them on their escape back to Allied lines. She died on 8 May 1976, aged 72, and was buried with her mother and father in the family grave at Hendon Cemetery, London. Recently Joanna’s life formed the inspiration for Leah Fleming’s historical novel – The Girl Under the Olive Tree – published in 2013.

On Oxi Day we should remember the bravery of all the women who took part in the defence and resistance of Greece. There are many war memorials on Crete but sadly none to this brave Anglo-Hellenic nurse and the hospital in which she served. There is a memorial nearby but no there is no mention of 1941, only the beautiful words of Cavafy to the brave dead. Maybe she was a victim of the anti-EAM prejudices of post-war Greece. Standing at the site of the hospital a few years ago, I thought maybe it would be time to have a memorial erected to Joanna and her part in the battle of Crete. Vale Joanna Stavridi, the Florence Nightingale of Crete.

Jim Claven is a trained historian, freelance writer and published author who has been researching the Hellenic link to Australia’s Anzac story across both world wars for many years, conducting field research and leading tours across Greece. He is the author of Lemnos & Gallipoli Revealed: A Pictorial History of the Anzacs in the Aegean 1915-16 and the forthcoming Grecian Adventure: Anzac Trail Stories & Photographs, Greece 1941. He can be contacted via email: jimclaven@yahoo.com.au