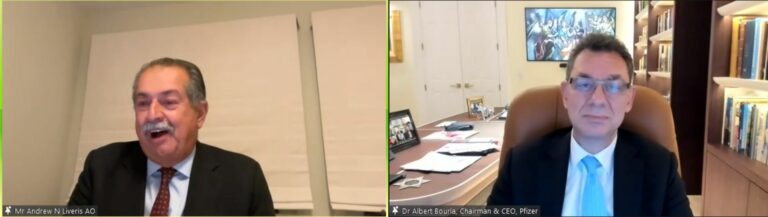

“If you are looking for Greek stories, I have a lot to tell and I’m not sure if some of these can be shared publicly,” Prizer CEO Albert Bourla told Andrew Liveris, the former chair of The Dow Chemical Company and who gives advice to the likes of US presidents.

It set the tone for a meeting organised by The Hellenic Initiative between two great men who have influenced the world, each in their own way. Mr Liveris, with a heritage from Kastellorizo, and Dr Bourla, born and raised in Thessaloniki to a family of Sephardic Jews who survived the Holocaust, by chance. His father happened to be absent at the time residents from his Jewish ghetto, including his parents, were taken to Auschwitz. His mother, too, was minutes away from execution by firing squad when she was spared via a ransom paid to a Nazi Party official by her non-Jewish brother-in-law.

“That gave her an optimism for life,” Dr Bourla said. “She became the kind of mother that would tell me, ‘don’t tell me you can’t do it, you don’t know what you can or cannot do’, or ‘don’t tell me this can’t be done, there’s no way you can achieve that because you don’t know what the future brings because look at me, I was in front of the firing squad and now I have you and your daughter’, and that gave me the optimism that I still have until now in trying to see the glass half full rather than half empty.”

The concept that anything is possible, is one he applied during the pandemic.

“For us, the biggest lesson was that people don’t know what they can and what they cannot do,” he said.

“If anything, they have tendency to severely underestimate what they can do. And people, they have the tendency to think within the box when the goal is incrementally proven, but when the goal is the transformational, very big target, they are forced to think out of the box, and they will surprise you with the results.”

READ MORE: Albert Bourla: It is only a matter of time to reach the end of the pandemic

Dr Bourla said that a vaccine usually takes eight years to make, but his team didn’t have that much time. “We didn’t ask them to do it in seven years or six – still, they would need to think incrementally on how they can improve the process. We told them you need do it in eight months, otherwise people would die. It was impossible to come even close without doing it very, very differently – and they did. We didn’t tell them you need to manufacture three million doses of those. Our annual manufacturing capacity before was 200 million doses. This is what we were doing across all the vaccines, across all the manufacturing sites. We didn’t tell them to do 300, we told them do three billion.”

Between March-July 2020, “we synthesized 600 different molecules and tested them”, he said. “This is a discovery process which takes years, and they did it in four months because that is what we asked them to do.”

Dr Bourla said that the important lesson is: “Ask the impossible and you will be surprised how close they will come.”

To change mindsets was no easy task. “When I told people that’s what you need to do, of course they were shocked. They were trying to understand what I am talking about, and how it was possible to do something like that. And clearly, there was resistance and denial,” Dr Bourla said.

The first plan offered by the team was a two-year plan instead of the usual eight years. “We would have basically a vaccine, around now,” Dr Bourla said. “I told them, ‘do me a favour, we will repeat the meeting on Thursday. I want someone to calculate from now until then, how many people will die’.”

Dr Bourla admits that was “psychological blackmail”. “But it worked, because they realised that it is not about us. We need to find ways otherwise it is going to be a disaster for the world. Failure was not an option,” he said, while adding that his team was told not to worry about money. He told them, “If we fail, we have bigger problems to deal with than writing off two billion, and they did it.”

Dr Bourla said that it is a balance of human responsibility and profits, necessary for the corporation. “If not us, then who?” he asked. “The economy would collapsed if we could not find a solution.”

READ MORE: Australia’s negotiations with Pfizer’s Chief Executive Albert Bourla via former PM Kevin Rudd

Equitable distribution

“There is a lot of misinformation,” Dr Bourla said regarding the equitable distribution of the vaccine. He said that for the vaccine to be distributed, we needed: (1) to have a vaccine, which was not a given about a year ago; (2) to have it at a price which everybody could afford.

The vaccine was provided to high income countries at a “cost of a take-away meal”, a fraction of the price of a COVID test. “What people may not know is that for middle income countries we priced it almost half of that and for low income countries we gave it at cost,” he said.

“Equity is not giving everyone the same, but giving more to those that need more.”

Governments were approached with these prices, and they were asked to place orders. “We were able, in the beginning in December, to forecast 1.3 billion doses,” he said, but was concerned when only high income countries placed orders rather than middle and low income countries “for a variety of reasons”, including promises given for manufacturing in their regions.

“Fast forward, November we announced the results, and the world was astonished,” Dr Bourla said. “December we started giving the first vaccine” to UK.

“By January, everybody started calling back.”

Australia was one of the countries that called back after other plans fell apart. “I think they bet on another vaccine producer,” Dr Bourla said. “Then of course they returned back to us. You know, they wanted the best for the Australian people.”

Instead of 1.3 billion doses, three billion doses were manufactured. “The first half was severely skewed towards high income countries but in the second half it is completely the opposite,” he said.

Following a deal with the Biden government vaccines are being offered for free to low income countries in what has turned into an unprecedented rollout.

Dr Bourla predicts that, in the future, all people will need to do would be to revaccinate, as they do with flu shots, adding however that different variants will appear, however we will go back to normal life “provided we are doing the right thing to get vaccinated”.

Beloved Thessaloniki

Last month, Dr Bourla inaugurated new centres for Digital Innovation and Business Operations and Services in Thessaloniki.

“I came up with the idea as we were looking to restructure our IT support around the globe,” he said, “and originally, there was resistance because they didn’t even know the city, but because I was the CEO they were forced to re-examined and they were surprised by the level of people who speak English.”

The initial investment of 200 data scientists to help Pfizer’s needs was a success story. “Things went so well that we doubled and tripled. So right now our plan is to recruit 700 people in Thessaloniki and we have hired 550. We were astonished with the level of talent. We got 15 per cent of them were people working abroad who found the opportunity to move back, 10 per cent non Greeks and 75 per cent Greeks from Greece. We are very happy with the quality of the people.”

He said there was “zero philanthropy” involved in the decision to invest in Greece, and says that IBM, Microsoft, CISCO, Amazon and more multinationals are seeing the benefits. “They are followers, and all of them called us,” he said. “And of course they will bring more and more.”

He sees opportunity in Greece. “I think there is great financial recovery and development, but wit a strong foundation this time,” he said.

“We had it in the pre-Olympics time but it collapsed because it was based not on production but consumption. We need to do it this time in a sustainable way. There are certain areas where we do have advantages and we can build on that. We can make Greece the Vanuatu of Europe. Why wouldn’t we attract the best talent from Greece?” he said.

“From our perspective, I knew that I could count on them and they wouldn’t embarrass me,” he said, adding that he knew of the many benefits of setting up a hub in Greece from his own experience.

“We are who we are because of our experiences,” he said, when pointing to the many Greek influences of his life, remembering playing at Navarino Square in downtown Athens, growing up surrounded by his family.

A Greek upbringing

“I was very much into the Greek culture. All my life until now, I was not the kid who listened to rock ‘n’ roll, I was listening to rebetika,” he said, remembering his early influences.

“I liked medicine and I liked animals, and when I was 18 years old I thought that was a good combination,” he said, adding that the rest was “chance, because I never wanted to go to industry”. He wanted a career in academia, and also important was for him to stay in Thessaloniki, and he viewed going to Athens as a “deal breaker”.

After finishing his PhD and completing his mandatory military conscription when Pfizer offered him an opportunity in Athens. “I didn’t really want to do it, but eventually they convinced me,” he said of going to Athens with a “heavy heart”. Initially he thought it would be a “sabbatical” to enrich his experiences for one- to -two years.

“In six months, I fell in love with both: Athens, which I found incredible, but I really did fall in Athens – it was an amazing city – and with industry. I felt that things were moving way faster than the university. I felt that over there I can have an impact,” he said. “So when the position back at the university opened and they told me, ‘come back’, I didn’t. So that was a pivotal point in my career.”

Three years down the road, Dr Bourla was given a promotion to Brussels. “Since then, I’ve lived in eight different cities of five different countries with Pfizer. A very big part of my career is the fact that I was exposed to different countries,” he said, adding that the main challenges were for his wife who followed him around the world with their children. “Without her support, that wouldn’t work. As they say ‘happy wife, happy life’.”

Dr Bourla said that his children benefitted from the “opportunity from very young to see that the world is not one thing” and “every single culture is valued and important”.