Minimum wages have become an important issue in the 2022 Federal Elections. Back in early 1980s, Economics 101 was telling us that increasing minimum wages would most likely lead to higher unemployment. Forty years later, Economics 101 and textbooks still teach the same narrative. Perhaps, our Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, was also guided by the same narrative when he recently opposed rises to the minimum wage to compensate for inflation for the lowest paid workers. Yet, Professor David Card was awarded the Nobel prize in Economics in 2021 for his work since 1994 on this subject and has shown that rises in minimum wages do not necessarily cause job losses. He also has shown that migrants do not displace existing workers. The principal reason for this result is that migrants, and the unemployed or low-paid workers, do not compete with the overwhelming majority of employed persons. In other words, the labour the lowest paid and migrants offer is not substitute for the work other workers do since they tend to take jobs that local workers cannot do or are unwilling to do. This is especially true in a knowledge economy with diverse skills and labour demand. The absence of a negative effect of minimum wage on employment has been confirmed in recent studies (Manning, 2021).

Recent research also indicates that a rise in minimum wages mitigates poverty and reduces inequality at the bottom of the income distribution (Engbom & Moser, 2021). Further, a higher minimum may have positive spillover effects on wage growth (McKenzie, 2018; Georgiadis, et. al., 2020; Kalb & Meekes, 2020; Ashenfelter & Jurajda, 2021). This possibility seems to work through three main transmission mechanisms:

(a) a direct effect whereby a rise in minimum wages helps lift incomes of the lowest paid workers and thus the average wage,

(b) existing employees push for adjustments to their relative wage, and

(c) firms have a stronger incentive to achieve efficiency and productivity gains.

With respect to wage growth, standard economic theory suggests that bargaining power, productivity growth and employment growth are key factors. Empirical studies suggest that weaker trade unions, changes in work force composition (e.g., ageing, part-time, women’s participation), slower labour productivity, the aftermath of the resources boom, and higher profitability have all contributed (Productivity Commission, 2020, p.24) but much remains unexplained. For instance, an emerging economics literature has paid much attention to the now broken link between wages and productivity. It also points to business labour hiring power (i.e., oligopsony) and precarious employment as more relevant factors.

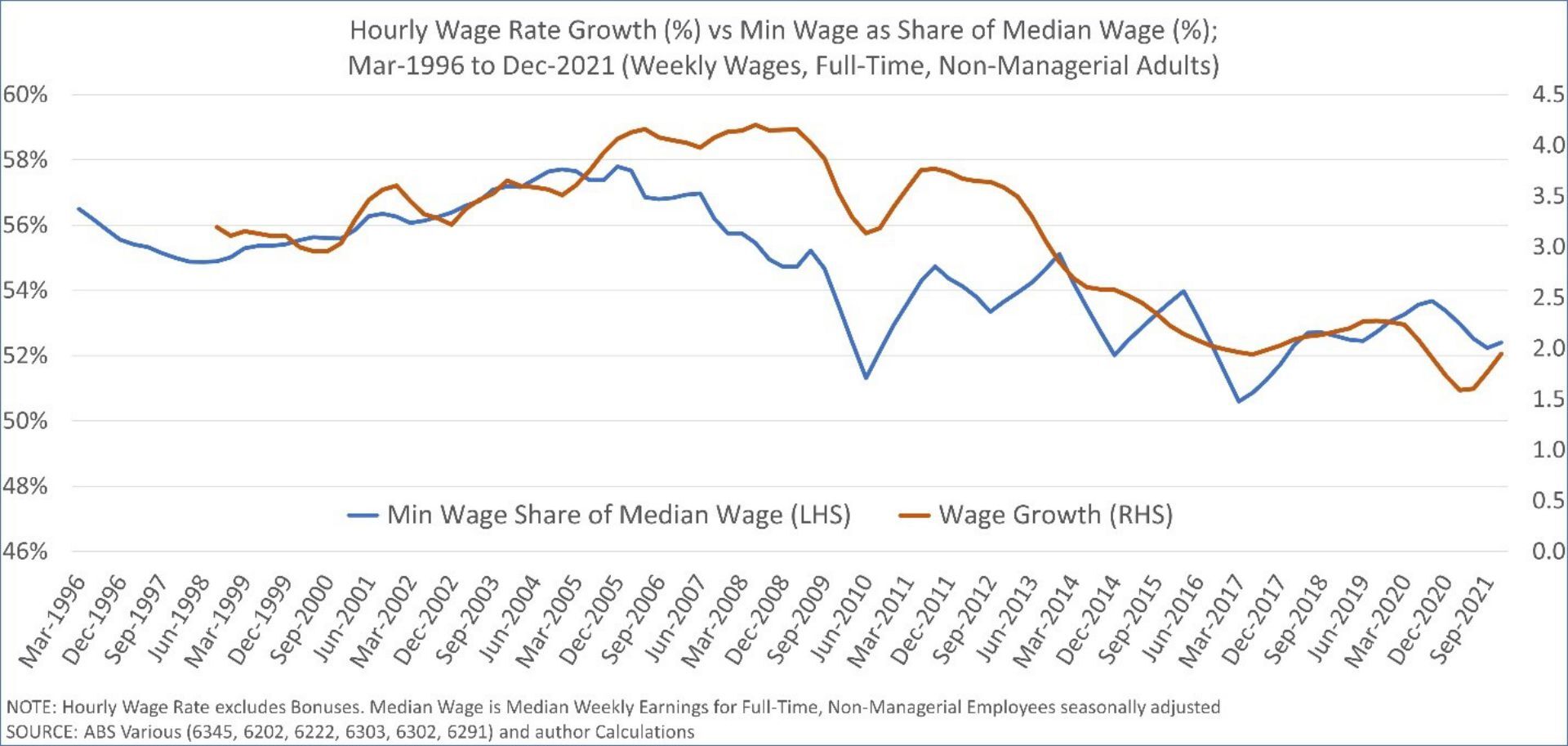

I present here the facts about minimum wages, wage growth and focus on the role of politics. Although there exist different awards and minimums, we focus on the very minimum wage which is currently set by the Fair Work Commission. It is a convention to examine minimum wage in the context of the current wages of the average full-time worker (i.e., median wage). Chart 1 shows the evolution of minimum wage share to the median wage of a full-time worker and that of growth in the hourly wage. The blue line depicts the minimum wage as a share of the median wage of full-time, non-managerial workers. From 56% it was in 1996, it is now 52%. Note also that both lines (i.e., the minimum wage share of the median full-time wage and wage growth) tend to track each other closely in a positive way (i.e., both tend to move in the same direction). This positive association does not necessarily imply causation but alludes to policy implications for the broader community, beyond the lowest paid workers. It also seems to suggest that our Prime Minister may be guided by old economic thinking. Modern economics today emphasises the role of “human capital” whereby workers are highly diverse in terms of education, skills, health, and abilities. These have become very important sources of sustainable growth in productivity, wages and living standards.

Chart 1. Minimum Wage as a Share of Median FT Wage & Wage Growth, Australia 1996-2021

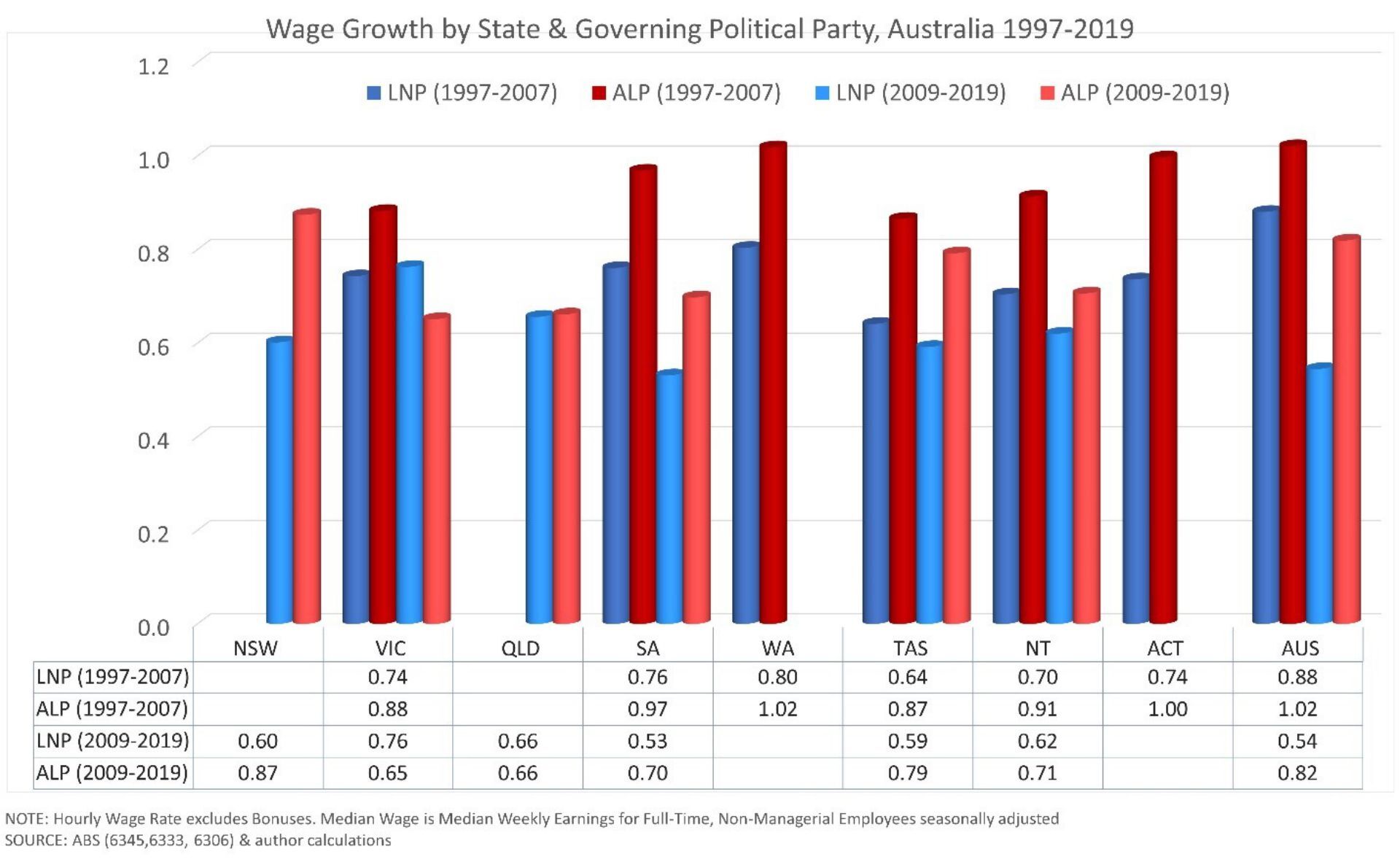

Next, we examine wage growth by state and Australia as a whole and compare the average growth rates observed when either the LNP or the ALP were in government. Chart 2 shows a clear pattern: ALP governments have consistently delivered higher wage growth than LNP governments since 1997. Note, the 2000 and 2008 periods were excluded due to unusual economic upheaval in the labour market as a result of the resources boom, and the GFC. Beyond the unlikely case of coincidence, differences in economic thinking & ideology may be some of the explanatory factors but it is also possible that a confounding factor is responsible for this apparent political effect. That is, a third factor may drive both (lower) higher wage and the electoral success of the (LNP) ALP party.

Chart 2. Wage Growth by State and Governing Political Party, Australia 1997-2019

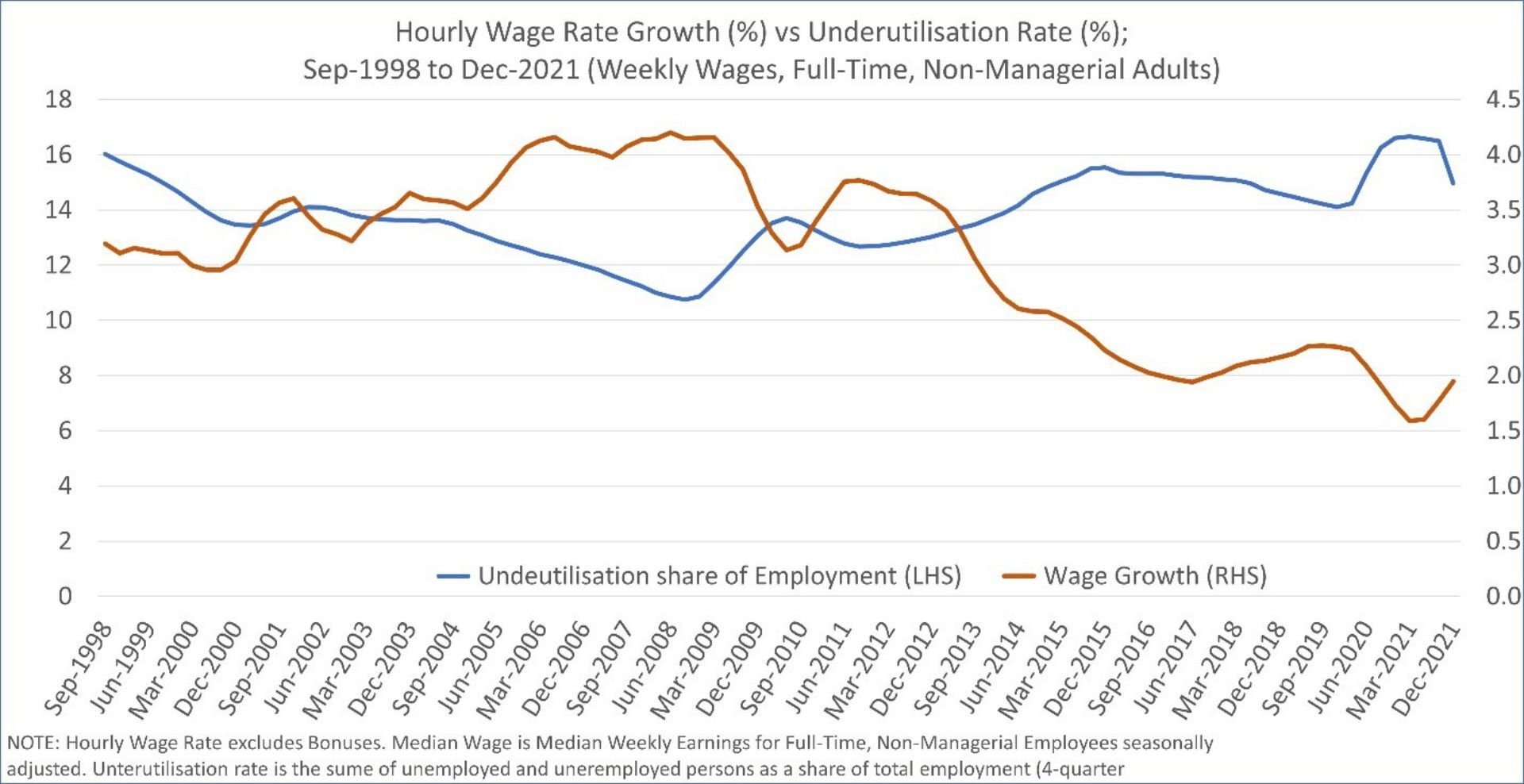

Preliminary work shows (see Chart 3) that the share of underutilised workers (i.e., the unemployed and the underemployed) in total employment closely relates to the political party effect; that is, there is increases in the underutilisation rate tend to associate with LNP governments. This makes sense since the size of workers looking for more work may weaken the bargaining power of existing employees in wage negotiations; the old argument of unemployment extended to underemployed workers. In theory, this does not exclude the political goodwill being an important factor in wage growth since difference in party policies could also be partly responsible for underutilisation and precarious employment.

Chart 3. Wage Growth and Labour Utilisation Rate, Australia 1998-2021

The nexus between the minimum wage and wage growth may not be exclusively an Australian phenomenon. Koester & Wittekopf (2022) suggest that in the 15 countries of European Union where a minimum wage exists, increasing the minimum wage can lead to wages growth. Georgiadis et. al. (2020) examine the Greek labour market using a panel matched employer-employee database for the period 2009-2017. They find that minimum wages in Greece positively contribute to individual and firm-level wages with wage spillovers even extending above the median wage.

The evidence so far is not conclusive and further research is required. However, it worth considering whether adjusting the minimum for the cost of living is not only helpful to the lowest paid workers but also for business innovation and aggregate demand towards a society with higher value-added production, good jobs and social inclusion.