Lupus, like many autoimmune diseases, can slip under your radar if your family is not impacted by it.

But for the estimated 1 in every 1,000 Australians affected, news of a scientific discovery opening the way to targeted treatments is music to their ears.

Lupus tricks the immune systems of millions worldwide into attacking their own cells. It manifests in ways ranging from skin rashes, joint pain and fatigue to problems affecting the heart, the lungs or the kidneys among other severe cases.

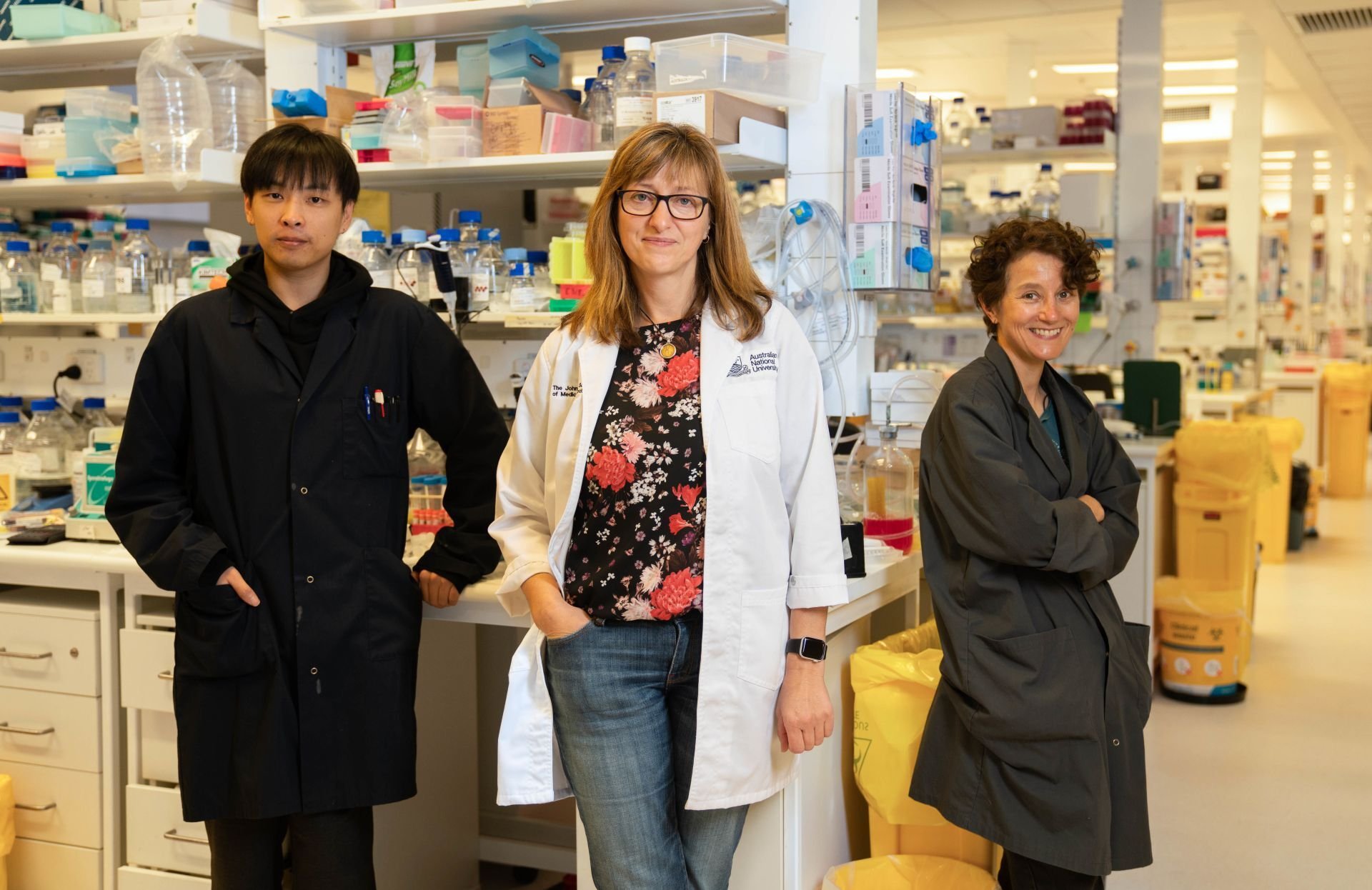

Vicki Athanasopoulos, from the Australian National University’s John Curtin School of Medical Research, has been one of the two supervisors of the study which identified a gene-driver of the disease, called TLR7.

It marks the “first time we have evidence showing a cause for lupus in humans,” she tells Neos Kosmos.

And there are hopes the study could have implications for the treatment of more autoimmune diseases, as well as contribute to the understanding of virus mechanisms, including COVID-19.

Led by ANU researchers, the five-year-long study was conducted by a team of over 40 international contributors spanning from the UK and Spain to the USA and China.

The gamechanger? A Spanish girl’s rare genetic mutation

Sharing glimpses of the breakthrough scientific process prompted by a patient, Dr Athanasopoulos recounts:

“One of our collaborators was a clinician in Spain with this young patient, Gabriella, who had early and severe lupus; she was around 7 years of age when diagnosed. So, we obtained blood from her and we sequenced her DNA from that blood looking to see what mutations might be contributing to her disease.”

La mutación genética de una niña ilumina las causas del enigmático lupus. El descubrimiento, en la española Gabriela Piqueras, revela los mecanismos de una enfermedad que afecta a millones de personas. Una investigación dirigida por @carovinuesa: https://t.co/A9fQJ1s5Mq

— Manuel Ansede (@manuelansede) April 27, 2022

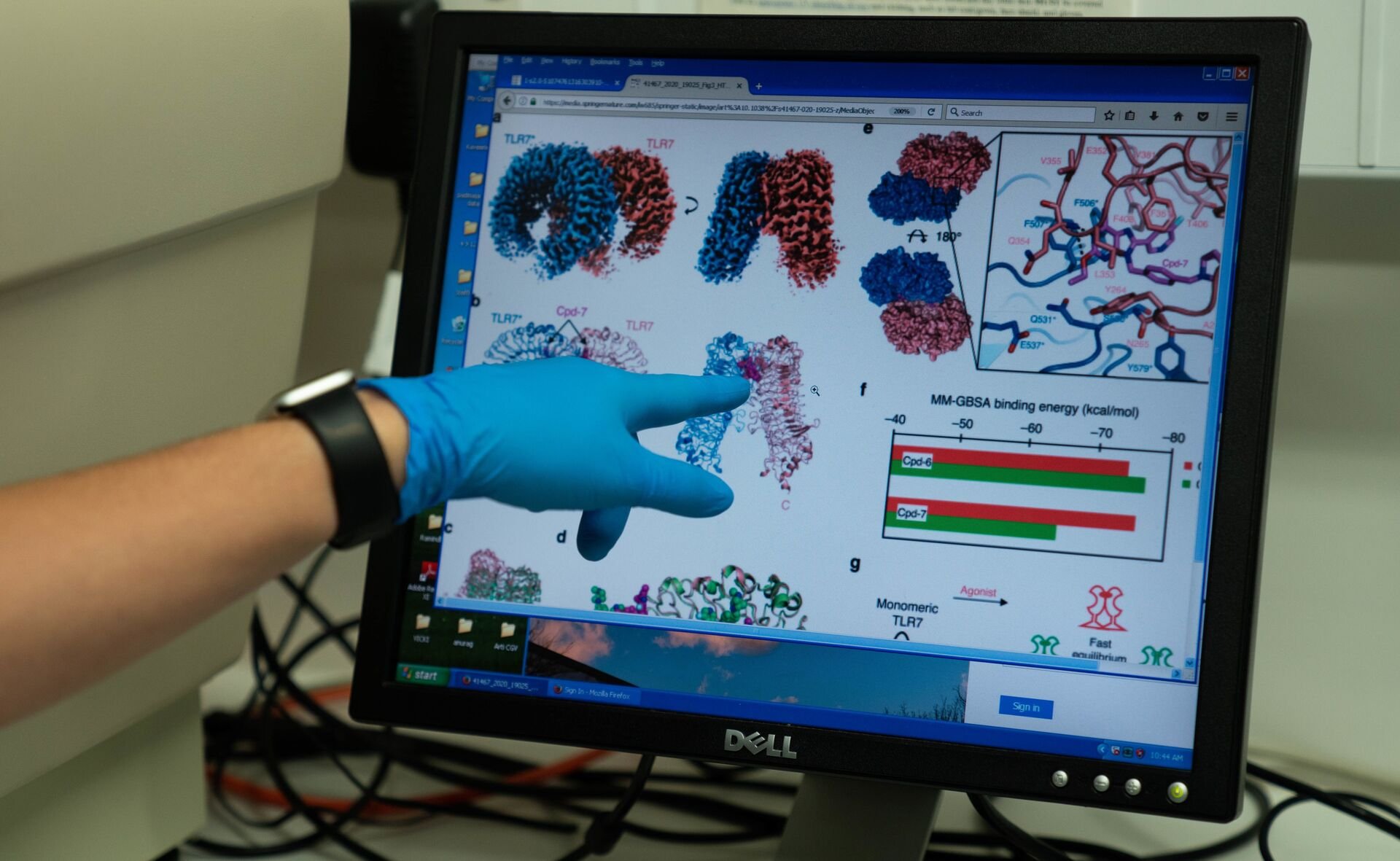

TLR7 was one of the genes that stood out as a candidate, due to the role it plays in helping the immune system recognise viruses, and the nature of the mutation it presented with, in Gabriella’s case.

“She had what we call a de novo mutation, which means that her parents didn’t have it, it came first with the girl,” Dr Athanasopoulos says of the genetic variation.

A variation which was responsible for the attack unleashed on some of the patient’s major organs, including heart and kidneys by her own body.

“The proof came when we took the same mutation that we found in the young girl and introduced it into an animal model and saw a similar disease in the mice. So that showed us that the TLR7 mutation causes lupus.”

The study may also help explain lupus’ ‘gender bias’, with odds of getting the disease being significantly higher for females.

“Interestingly, the TLR7 is located on the X chromosome, so we think that might be one reason why women are, say, nine times more affected by lupus than men ” Dr Athanasopoulos says.

The effect of an overactive TLRF7 gene, she explains, can be double for women as they have two X chromosomes, as opposed to men who have only one.

Culprit found. Now, what?

While not every lupus patient has an overactivated variant of TLR7, confirming it is a lupus-causing gene paves the way to the development of new targeted treatments.

“If you can identify what gene is involved, you can identify a pathway that you can then try and either repurpose current drugs or develop new ones to try and treat and specifically target that gene pathway,” Dr Athanasopoulos explains.

Initial trials for novel drug therapies have already started and one of the next steps for the team will be to examine a potential application of their findings in conditions beyond lupus.

“We think that the TLR7 pathway might be overactive in other autoimmune diseases. And we’re looking at proving or disproving whether that is in fact the case.”

The prospect of better understanding coronavirus and other viruses is also among gains from the new findings, due to the TLRF7 receptor function in detecting viruses.

Dr Athanasopoulos cites at least two studies published during the pandemic showing that some patients experienced more severe COVID disease, due to mutations causing their TLR7 receptor to deactivate.

1/ In this first @SciImmunology paper (https://t.co/1uTHUO7w9c), we show that at least 1% of men younger than 60 years with life-threatening COVID-19 are sick because of X-linked recessive (XR) TLR7 deficiency.

— Casanova Lab (@casanova_lab) August 19, 2021

“So, it’s like a balancing act. You don’t want too much active TLRF7 [the mutation found causing lupus] and you don’t want too little because you need to be able to fight off infections,” she explains.

Tailored therapeutics for patients

Genetic nuances can be crucial in developing drugs for targeted treatments.

“Part of it is knowing which pathways to target, understanding the genetics and the molecular basis of the disease,” Dr Athanasopoulos says.

And the second generation Greek Australian has the expertise to support this mission.

“I’m a molecular biologist so interested in how molecules work and the nitty gritty detail involved in that.”

Her heritage is credited for a less common weapon in her arsenal as a scientist, with knowledge of Greek coming handy in medical themed vocabulary.

“It helps me understand the meaning. So, when you come across a complex medical term – because I didn’t do medicine, I did science – you can sort of break down the word and be like ‘ok, I think I know what that means’. And the strange thing is, when I see a Greek word like that, I can’t pronounce it in English. I have to say it in Greek. ”

Asked about hers and her team’s aspiration to offer some reprieve to lupus sufferers with novel therapies, Dr Athanasopoulos explains the daunting task is worth the trouble for a condition with no cure and for which treatment options are minimal.

“Lupus is very complex. You have like 11 different symptoms, and you only need four of those markers to be characterised with lupus. And it can range in severity and the cell types that are affected and the organs that are affected.”

But the outlook is optimistic, following the identification of the lupus-causing gene.

“With an understanding of what’s driving the disease, you can have a better understanding of how to treat it.

“We are now trying to improve the process of screening mutations that we find in the DNA of patients, so that we can show which ones are likely to have an effect and cause disease and which ones are not.

[…] I think we’re at the edge of personalised medicine, where we can, you know, target a particular patient or group of patients more effectively, because we know that in that group of patients, this is what’s gone wrong. And these are the right drugs to treat them with.”