I often think of the journey of historical enquiry as a constantly changing painting or image, being added to as new researchers uncover aspects of the past that have been ignored or skimmed over. Sometimes new enquires, uncovering new evidence are added, while previously highlighted aspects become dimmed and less significant. This is how our understanding of the past is constantly enriched.

I think of my own experience of primary school, where the teaching of Australian history was primarily one of explorers and settlement, with barely a mention of the indigenous population that was displaced and traumatised by the experience of contact. I can still recount the names of many of the explorers, as if I had learned them by rote. Such an interpretation of Australian history would now be considered inadequate, to say the least.

Such is the case with our understanding of our Anzac tradition. The substantive role of women in the Australian Anzac story is now broadly appreciated, with the Australian nurses who served on Lemnos during the Gallipoli campaign – and in First World War more generally – widely understood. It was not too long ago that the service of Australia’s indigenous service personnel was unacknowledged and even denied by some public commentators. This would now be regarded as ignorant or worse. The service of indigenous diggers – such as Reg Saunders – is now rightly commemorated, an important part of our Anzac story and the history of Australia more generally.

Recent years have seen a number of major new publications address the contributions of various communities to the Anzac story. Mark Dapin’s seminal Jewish Anzacs, Elena Govor’s Russian Anzacs and John William’s German Anzacs and the First World War all revealed the contribution of these nationalities to Australia’s Anzac story. And of course, Steve Kyritsis’ volumes on Greek born and heritage Anzacs is a standard work on the topic. More recently, studies – such as Joan Beaumont’s Serving our Country: Indigenous Australians, War, Defence and Citizenship – have told the vital part that our indigenous community played in this story. All of these works drew on detailed historical research into the Anzac record, bringing to light these important aspects of our past.

It is in this context that I approached the new history by June Factor.

June tells the story of the estimated 4,000 Australian soldiers in the Second World War who served Australia’s war effort but not in fighting or front-line units. They were referred to as “aliens” – non-British subjects – many born in other countries, among the 50,000 then resident in Australia at the outbreak of war. As June says they came from all walks of life, whether scholars or farmer labourers, of many faiths and none as well as and expressing varied political beliefs. They were a multicultural military force before the term multicultural had entered common usage.

These were the men of the Australia Army’s Employment Companies, modelled on the British Army’s Pioneer Corps, and established in 1942. They laboured under standard Army regulations, lived in tents and huts, loaded and unloaded trains, worked on wharves, cut timber and transported goods. They held fundraising concerts and raised money for good causes.

The book recounts the story of how many of the recruits originally made their way to Australia and their life here before their recruitment into the Army. It then describes their experience of Army life and the tasks they were engaged in by the various Employment Companies. The issue of enemy Aliens as well as the religion and politics of the various recruits is discussed. Specific attention is given to Chinese, Indonesian and Timorese recruits.

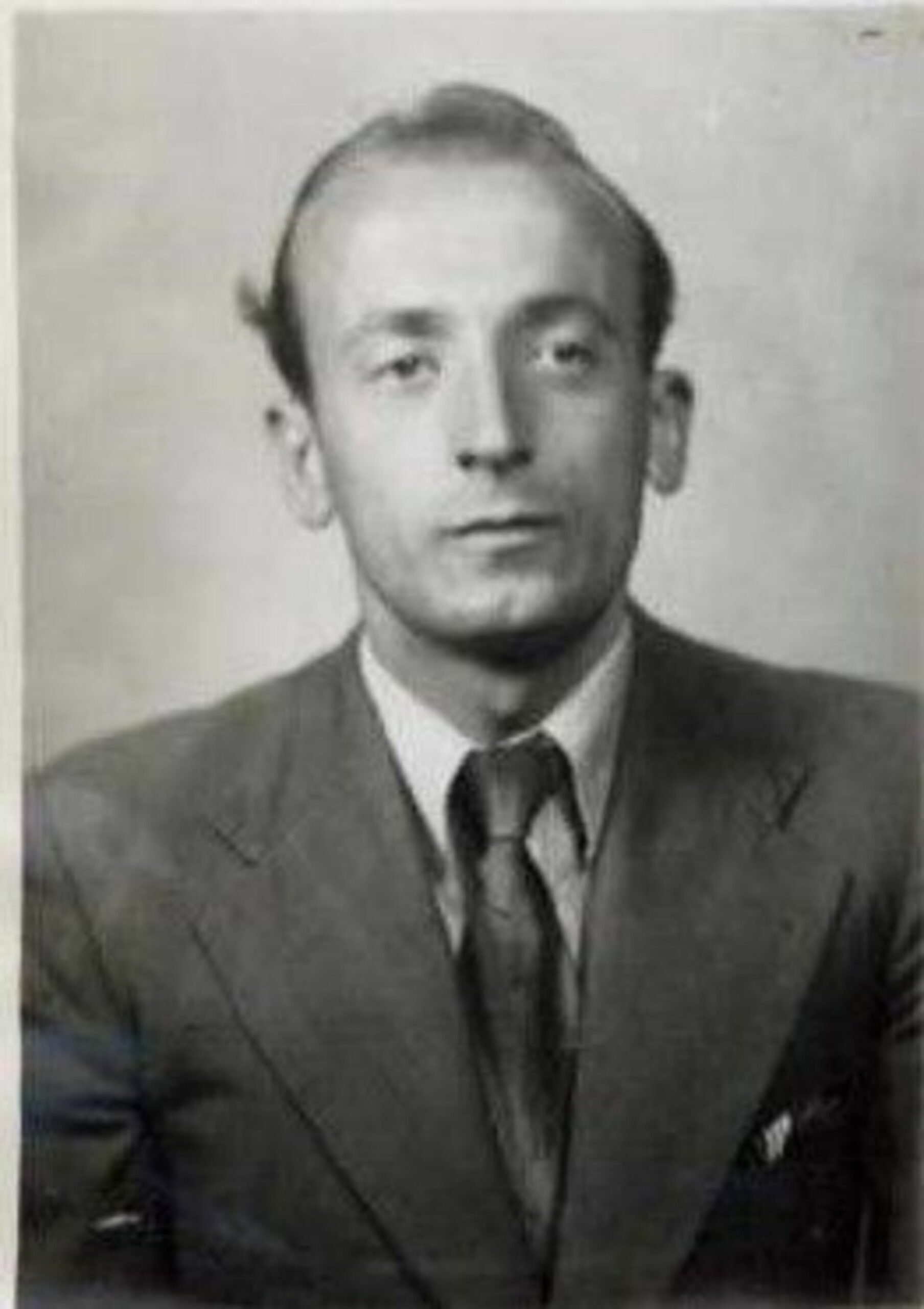

June also recounts the experience of Jewish recruits, many having fled the rise of fascism in Europe only to face internment and prejudice in Australia. One of these is the author’s father Saul Factor (or Faktor), who had arrived in Melbourne with his family from Poland in 1938 and who would serve in the Employment Companies from 1942 until 1945.

The book also tells the story of the prejudice experienced by many so-called “aliens” during the war, including that faced by Jewish refugees. But she also reveals the active work in support of those facing discrimination – both in terms of being allowed to enter Australia and to participate in Australian society – by individuals and organisations like the progressive civil liberties advocate Brian Fitzpatrick and the Australian Council for Civil Liberties.

Readers will be interested to read the references in June’s book to John (Constantin) Callinicos. He had arrived in Australia in 1936 as a fourteen year old from the Island of Ithaki, the son of Spyros Callinicos. By 1942 he was working in a fruit shop in Toorak Road, South Yarra. It was here that John and his employer received their call-up papers. They were to report to the local call-up centre in a local hall to determine their suitability for military service. John was duly accepted into the Army and marched up Punt Road – along with his fellow recruits – where they caught the train to Caulfield Racecourse and the Army camp established there.

Young John soon began his military service with his Employment Company. The sort of labouring tasks he was engaged in are detailed in the book – from loading stores, drying hessian, digging slit trenches around Melbourne, stacking timber, loading petrol drums, unloading onions and working at Victoria Dock. Sometimes their conditions were harsh, provoking a reaction from the recruits. A hunger strike in response to needless marches – to and from the camp and the nearby railway station, four times a day – saw the Army supply transportation for the men. John would serve from 18 March 1942 until his discharge on 14 August 1946. After the war John would list his occupation as a delicatessen owner. No doubt there are many more stories of other Hellenic-heritage members of these units remaining to be told.

As can be expected from such an author, the book is well-researched and authoritative. In this book the author shines a light on this little researched area of our history, one that was perhaps in danger of being forgotten, now bringing it to a wider audience. It represents an important contribution to the history of both Australia’s migrant and multicultural story but also the history of Anzac. I highly recommend it.

June Factor’s Soldiers and Aliens: Men in the Australian Army’s employment Companies during World War II is published by Melbourne University Press and is available from all good bookshops.

Jim Claven is a trained historian and published author, who has been researching the Hellenic link to Australia’s Anzac story over many years. His most recent publication is Grecian Adventure. He can be contacted via email – jimclaven@yahoo.com.au.