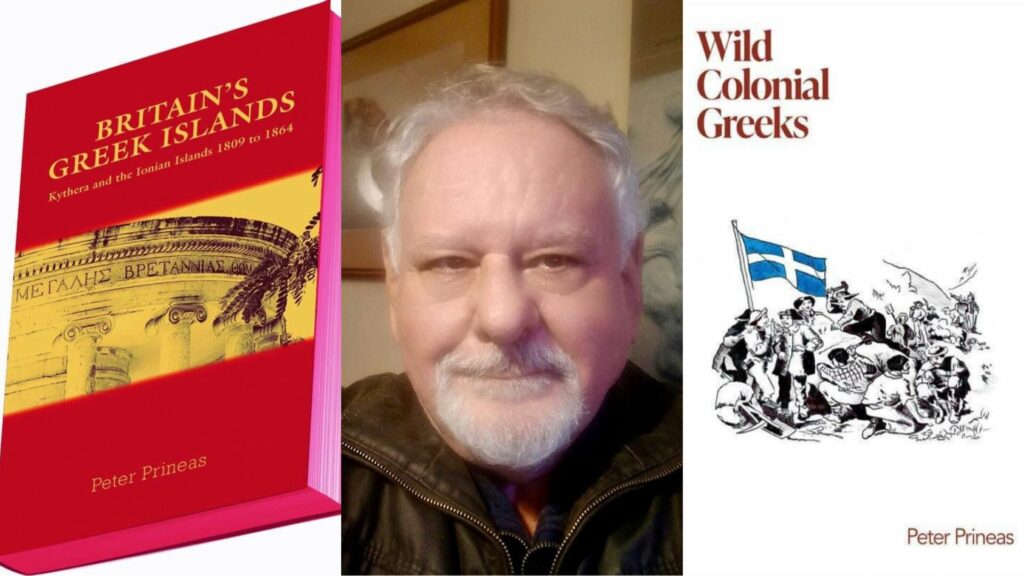

The surprise of seeing an important Australian settler artefact in a Kythera’s modest museum led Greek-Australian writer Peter Prineas OAM on a sojourn that yielded two books in his Greek-Australian history trilogy Britain’s Greek Islands (2012) and Wild Colonial Greeks (2020) that explore the early links of Greeks to Australia and which opened new information for modern readers.

His father, Demetrios (Jim), came to Australia aged 16 from Kythera in 1922 and Peter who grew up in New South Wales was only to visit his father’s island for the first time when he was 29. It was during one of these visits that he saw at a local museum a pictorial proclamation board to Tasmania’s Aboriginal community that had been issued by Sir George Arthur, the Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (1823 to 1836).

Mr Prineas realised that the island’s links to colonial Australia were more significant than he had first thought. For much of the 19th Century, Kythera, which is off the southern Peloponnesian coast was part of the British Protectorate of the United States of the Ionian Islands (1815 to 1864) with the capital in Corfu. The British connection to the islands was one reason why so many Greeks from the islands were to feature early in Australia’s history.

But it was his family’s own story that first drew him to research and write his books about the early presence of Greeks in Australia.

Mr Prineas said over the years he has done a lot of things, he was a lawyer in the NGO environment, worked as a parliamentary adviser. He is also a professional writer who also focussed on wilderness and conservation issues – he wrote Colo Wilderness (1978) and Wild Places (1983) – and worked for Readers’ Digest.

Mr Prineas first turned to the Greek-Australian experience when he came across a story that Bingara a New South Wales town was renovating and restoring the former Roxy Theatre.

“It was the Roxy restoration that set me up in Greek-Australian history. I am a diaspora Greek and it was just chance that set me off and it led to three books being written.”

The Roxy as a cinema had ties with his maternal grandfather, Panayiotis Firos (nicknamed Katsehamos) who owned a café in the town in the 1930s and through his partners became connected to the cinema.

“The Greek café owners of those times knew what drew the crowds in the evenings and (as a result) many of them owned cinemas,” said Mr Prineas. Greeks played a significant role in popularising cinema as a form of entertainment in Australia.

“I found out about the big reopening of the Roxy and that the story of the Greek connection was being overlooked. So, I wrote the story of my family’s links to the Roxy and the people of Bingara embraced the story.”

Mr Prineas who is based in Sydney went to the town for the opening of the Roxy as a museum. He became its curator and the museum was to receive a prize for its displays and videos that reflected the story of the town’s cafes morphing into the cinema.

It was that personal family link that he developed into his 2006 book Katsehamos and the Great Idea which Greek-American author of Eleni and Pulitizer Prize winner Nick Gage praised for “reflecting the aspirations of all Greek immigrants of my father’s generation, a world that has faded from the collective Greek consciousness as much as the Great Idea. Most of all, however, I was struck by the literary quality of the book which is far superior to almost all works of this type that I have read.”

Mr Prineas’ maternal grandfather, Panayiotis Firos (Peter Feros), had come to Australia in 1920, having fought in the two Balkan wars (1912 and 1913) and then on the Salonica Front (1915-18). He married and had a child when he was called to fight again, this time in Asia Minor, weary of fighting, he decided to migrate to Australia aged 31.

For the next 10 years, his grandfather remitted money to his wife, Maria, who had given birth to their second child soon after he left for Australia. He bought a café in Bingara which was doing well so in 1930, he felt secure enough to return to Greece to be with his family while leaving the business in the hands of his partners. On his return to Bingara he found his partners had stacked up debts when they over-extended their resources and bought a block of shops and the Roxy cinema.

Panayiotis moved to Murtoa, a small town in western Victoria to start again. He opened a new shop and he at last was able to bring his family from Greece in 1947. He died in 1954.

Peter Prineas’ next book on the Greek presence in Australia was Britain’s Greek Islands (2012) which was triggered by his unexpected encounter in the Kythera’s museum of Lieut Gov Arthur’s Van Diemen’s Land proclamation.

In carrying out his research for the book, he received support from the Nicholas Anthony Aroney Trust which had been set up to help preserve, promote and foster the island of Kythera, and Kytherian and Greek heritage, culture, ethos, and history. The trust had earlier provided Mr Prineas with a grant to help publish Katsehamos and the Great Idea.

Mr Prineas travelled to the islands, and visited the British archives in Kew. He examined thousands of documents, he photographed 10,000 of them to bring back and study more closely on his return to Australia. Many of the documents were handwritten making the task of extracting information more challenging.

“Travelling around Kythera, there is still evidence of the British presence in the schools, bridges and infrastructure. I would travel with a great uncle who would point them out to me.”

“Kythera did not have a good natural harbour like Ithaca. The Kytherans would go to the Peloponnisos or Smyrna. They had a habit of emigrating for work going further afield and eventually that led many of them to Australia.

While many in the Ionian islands did not speak English, upper-class students would have learned English at school which would have given them an advantage coming to Australia.

Many islanders who had a close connection to the sea would find work on English merchant ships plying the islands and beyond. A number of the seamen would leave their ships in Melbourne to go to the goldfields in the 1850s. The rate of desertion was so high, that Mr Prineas noted on 6 January, 1852, 35 ships lay off Melbourne because they did not have sufficient crew members to sail.

“Corfu Reef” and “Ellas Reef” are but two examples of a sizeable Ionian Greek presence in Australia’s goldfields.

Mr Prineas then went on to write Wild Colonial Greeks in 2020 gleaned from a vast number of newspaper articles many of which he accessed through the Trove website (https://trove.nla.gov.au/), a collaboration between the National Gallery of Australia and hundreds of partner organisations. It includes digital copies of websites, Government Gazettes, maps, magazines, newsletters and many other resources.

He likened his work of uncovering the various stories from official documents to gaining a wider understanding like the miners themselves following seams of ore to uncover big nuggets of gold.

“I am happy with the work as I looked at the characters (in the documents) as human beings and filled out their lives.”

He said there was material in Trove that would keep busy many a budding Greek-Australian historian.

His advice to anyone wanting to write about their history was first to talk to their elderly relatives and family friends about their experiences.

“I spoke to a lot of people who had never been asked before about their experiences during the wars and coming to Australia. A lot of what I wrote came from direct interviews. … I regret that I did not speak to more old people before they died. So ask the old people in your family.”

He advised that one has to develop an in interest in finding out where official sources of information were kept and how to access them.

“You learn as you go,” Mr Prineas said.

* Katsehamos and the Great Idea and Britain’s Greek Islands are available to buy through the Kytherian World Heritage Fund (website link: https://kytherianassociation.com.au/about/sub-committees/kytherian-world-heritage-fund/). Wild Colonial Greeks is published by Australian Scholarly Publishing.