If you want to really roast someone these days, social media offers ample opportunity to do so in a multitude of ways. If you want to do so without the recipient necessarily knowing that you are doing so, you could excoriate the object of your derision in a private group, or under an assumed profile, a decidedly unhellenic act for it is the clash and conflict over the ether that satiates the keyboard warriors of our clan’s thirst for lectical combat.

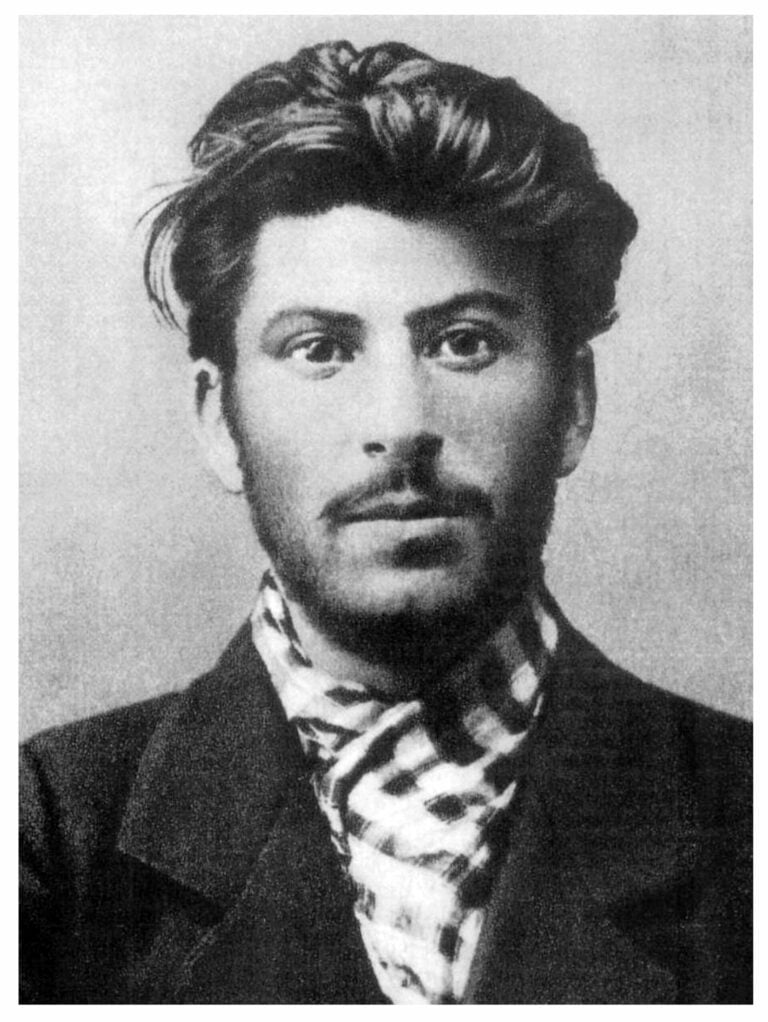

If on the other hand, you are living in the Soviet bloc during the time of Stalin, an epoch when one incorrect word could grant one a one-way ticket to the depths of Siberia, where there is definitely no wifi and the only influencers carry truncheons, ways to register one’s scorn are few and far between. Osip Mandelstam, the famous Russian poet, found this out the hard way, when in 1933, he bravely penned as part of his Stalin Epigram the following lines: Thick fingers, fat like worms, greasy, / Words solid as iron weights, / Huge cockroach whiskers laughing …”

Mandelstam died on the way to the Gulag, but as the research of scholar Han Baltussen in A Homeric Hymn to Stalin reveals, Czech author Vaclav Pinkava, who also expressed his contempt of Stalin in lyrical form, survived, mainly because he wrote his satirical piece in Homeric Greek. Choosing such an archaic form was a stroke of genius, considering the esteem in which European civilisation holds Homer, even when few have the facility to read him in the original. Thus, Pinkava was able, through the adoption of Homeric language, to parody the hagiographic hymns prevalent in Stalin’s day and beyond, in relative safety, satirising the mythological proportions afforded to Stalin by Communist idolatry. Most importantly, he managed, through Homeric Greek, to develop a remarkably subversive vocabulary of criticism and resistance.

Drunken daring

First penned in 1948, the poem ended up in Pinkava’s novel Gravelarks, set towards the end of the Stalin era, where the main protagonist, Zderad, who studies ancient Greek, pens the poem in a moment of drunken daring, only to be blackmailed about it years later.

From the outset, we are presented with an omnipotent figure, who, if not for the fact that he is identified by name, place and nationality, could easily be mistaken for Homer:

Στᾶλιν, ἄναξ, ἄγαμαί σε· σὺ λευκολίθῳἐνὶ Κρέμλῳ / ἑζόμενος κρατέεις πάντων Ῥώσσων Τατάρων τε / καὶ πολλῶν ἐθνῶν ἀμενηνῶν κράτων. / Ἕρποντες κονίῃ σε θεὸν ὣς εἰσορόωσιν.

Hans Baltussen offers the following translation: Stalin, lord, I revere you: you, seated in the white-stoned Kremlin, / Rule over all Russians and Tartars / and many powerless peoples, /who drag their feet in the dust and gaze upon you as a god.

It thus becomes apparent that “Homer” is in fact, through exaggerated praise, parodying and ultimately subverting the cult of personality developed around Stalin, even as it purports to celebrate his almost divine authority. This ostensible praise of his power will continue in the next verses where the rhapsode will indicate the effects that the emanation of Stalin’s might have on others: Σοὶ δὲ μέγας στρατός ἐστι βροτοκτόνος, ὃς τ’ ἐνὶ χώραις / ἀλλοδαπῶν φορέει γ’οἰζὺν καὶ κῆρα μέλαιναν·/ Ἄνδρας συλεύουσι βιάζουσι τε γυναῖκας, / ὡρολόγους γὰρ κλέπτουσιν τοὺς ἄνδρες ἀγαυοί / ἐν καρποῖς φορέουσι·τὸ γὰρ μέγα θαῦμα ἰδέσθαι. / Ἄλλοι γὰρ ῥ’ ἐκάμοντο ἰδυίῃσι πραπίδεσσιν, / σὺ δ’ ἐλθὼν αἱρεῖς, ὅτι τοι κράτος ἐστὶ μέγιστον·

You have a great man-murdering army, which conveys / into alien lands, misery and the plague. / Men they kill and women they rape, / Watches they steal from the wrists / of valiant men; truly marvellous to behold. / For others have toiled with great ingenuity, / But you appear and take them for your power is immense.

Timepieces

While there is no word for wrist-watch in Homer, Pinkava’s suggestion, ὡρολόγους, is inspired, being close to the Hellenistic Greek ὡρολόγιον for clock and while lauding the acquisitive might of Stalin, he is actually drawing attention to the occupying Soviet army’s soldiers propensity to steal wristwatches from vanquished Germans. Phrases such as μέγαθαῦμα, also appear in Byzantine Orthodox hymnology, with the “miraculous” nature of Stalin, juxtaposed against the grubby depredations of his minions. The fact that Stalin began his career as a seminary student renders the use of such polyvalent phrases downright cheeky.

Timepieces are important in the poem with the Homeric rhapsode proceeding to portray an almost Titanic Stalin with absolute sway over creation. Surrounded by watches and chronometers, both symbolic of loot, poor taste and of order and control, could the poet be paralleling Stalin with Kronos, the primeval god who swallows his own children and keeps the rest of the world in quailing subjugation? Or is he slyly hinting that even as he is at the apex of his powers, the Master Timekeeper’s time is limited, especially since according to variants of the ancient myth, Kronos was relegated to his own special type of gulag, Tartarus?

Χεῖρας βεβριθὼς παμπόλλοις ὡρολόγοισιν / ἑζόμενος γ’ ὁράας χρονοδείγματα κύδει γαίων. / Πάντες δειδιότες κυνέουσι πόδας πυγήν τε, / Αὐτὸς γὰρ κρατέεις καὶ γ’ οὕστίνας οὐκ ἐφίλησας, / Πέμψας Σειβιρίνηδ’ εἰς λάγερα, ᾗ ψύχωνται / δεσμοῖσι στυγεροῖσι δεδημένοι ἠὲ θάνωσιν.

With your many watch-laden hands / You sit and watch your time-measurers, elated in your pre-eminence. / All kiss your feet and arse, / For you rule and whoever you don’t like, / you send to Siberia to a camp, here they freeze / bound in loathful chains or die.

In the last lines of the Ode, we learn just what type of effect such omnipotence has on those who are compelled to worship him and upon whom his will is absolute:

Ῥωσσιακῆς γαίης πάντες ῥ’ ἄνδρες τε γυναῖκες, / εὐχόμενοι στυγέουσιν, ἐπεὶ θεὸς μέγιστος / Ἠέλιον δ’αὐτὸν φασιν σόν τ’ ἔμμεναι ὄμμα / καὶ Στάλινος πόρδην φασι ψολόεντα κεραυνόν.

All men and women of the Russian land / Pray to you even as they detest you for you are the greatest god. / They say the sun itself is your eye / and that Stalin’s fart is a smoking thunderbolt.

The sun and Stalin

The idea of a god so terrible and mighty that it is agony to even worship him under duress is here linked the Sun, an entity that gives us life and presumably can take it away, and which we cannot behold or approach without incurring harm. Here the poet is slyly commenting on the extent to which the sun became a central image in Stalinist propaganda, with Stalin unambiguously equated with the sun in Soviet poetry and song, not only because in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, the Sun is held to be the only entity that has borne witness to the abduction of Persephone but also because the imagery of the Sun of Righteousness offering vindication and healing would have been all pervasive in the pre-revolutionary Orthodox culture, permitting the reader to compare that sun of vindication with Stalin’s sun of destruction and death.

The equating of Zeus’s main attribute with Stalin also serves to parody, in bawdy Aristophanian fashion, the self-importance of the man and the powers attributed to him. Whereas a thunderbolt cast by the hand of Zeus may be a fearsome prospect, Stalin’s thunderbolt, though equally as dangerous, is illegitimate, coming as it does as a product not of his mightiness but rather, his flatulence, that is, his inability to control himself. The fart joke employed here as a chief expression of derision can be compared with a similar expression, in lyrical form, in the Old Testament book of Isaiah, 16:11: “Wherefore my bowels shall sound like a harp for Moab, and mine inward parts for Kirharesh.”

The poet’s attempt to encode criticism in the Greek language in order to render it safe has cultural precedents in antiquity, with Cicero employing Greek when seeking to make jokes that only the initiated could understand. There are concordances in Stalin’s Hymn to Homer’s verses that can only truly be appreciated by those who are fully conversant with the Homeric epic and are across its nuances. The ensuing “in-jokes” are reminiscent of the intertextual banter between Byzantine scholars, the classical allusions of whom are often lost upon us, employed to undermine each other and to criticise their rulers, again underlying just how safety may seem to lie in the classics.

Ultimately, in the novel, Homeric Greek fails to provide the main protagonist with the security he seeks, the prospect of his exposure culminating in a murder. Yet as an exercise in highlighting how subversive criticism can be encoded within a linguistic medium that has been the chief bearer of Greek mythology to the western world, Pinkava’s whimsical Homeric Hymn to Stalin remains a testament to the role of the Greek language as a form of resistance against oppression, and its ability to give nuanced voice to the suffering of millions. And the irony does not end there. In January 1913, a man whose passport bore the name Stavros Papadopoulos disembarked from the Krakow train at Vienna’s North Terminal station.

That man, was Joseph Stalin, using a fake Greek name.