Many Neos Kosmos readers will be aware of the post-WWI refugee work of Ballarat-born Major George Devine Treloar who helped over 100,000 Christians refugees from Asia Minor resettle in northern Greece in the wake of the Asia Minor catastrophe. George Treloar rightfully deserves recognition in this year, the centenary of that catastrophe.

Recently a new aspect of George Treloar’s refugee work has come to light. George’s son – David Treloar – recently sent me a photograph from his father’s extensive collection. He was unsure of the location of the photograph but felt that it may have been taken on Lemnos.

Treloar was a British Army Major who had been attached to the anti-Bolshevik Russian army as a Colonel and was thus evacuated from the Crimea to Constantinople in November 1920 along with 150,000 Russian refugees, in the face of the final Bolshevik advance. Constantinople, the Ottoman capital, was then under post-war Allied occupation and administration.

These refugees required urgent support in terms of accommodation and sustenance, arriving as they did with little means of support. Various camps were soon established, including at Tuzla on the Marmara coast, south-east of Constantinople, and on the Gallipoli Peninsula. George was appointed commandant of the Tuzla camp.

Russian refugees were also moved to Lemnos. It is estimated that some 24,000 refugees would be accommodated there, mostly Don and Kuban Cossacks along with their families. They began to arrive in November 1920; some camped near Mudros Town or near the village of Romanou, others at the largest camp established on the Turks Head Peninsula. Historian Bruno Bagli writes that after reaching a peak in February to April 1921 of 21,000, the camp populations steadily declined. The Mudros and Romanou camps were closed in June 1921, that on the Peninsula later that year.

The location of the main camp on the exposed Peninsula may seem surprising. The experience of the Allied medical and other facilities based there during the Gallipoli campaign should have been noted by the French administration of the Russian camp. The archives and records of the Australians nurses and soldiers who were based here from August 1915 until the following January stand testimony to the difficulties of life on this exposed peninsula. They tell of exposure to the heat and insects of summer, of wind and floods in winter, their tents being blown down. Many suffered from dysentery and pneumonia. Two Canadian nurses would die of illness during their time here.

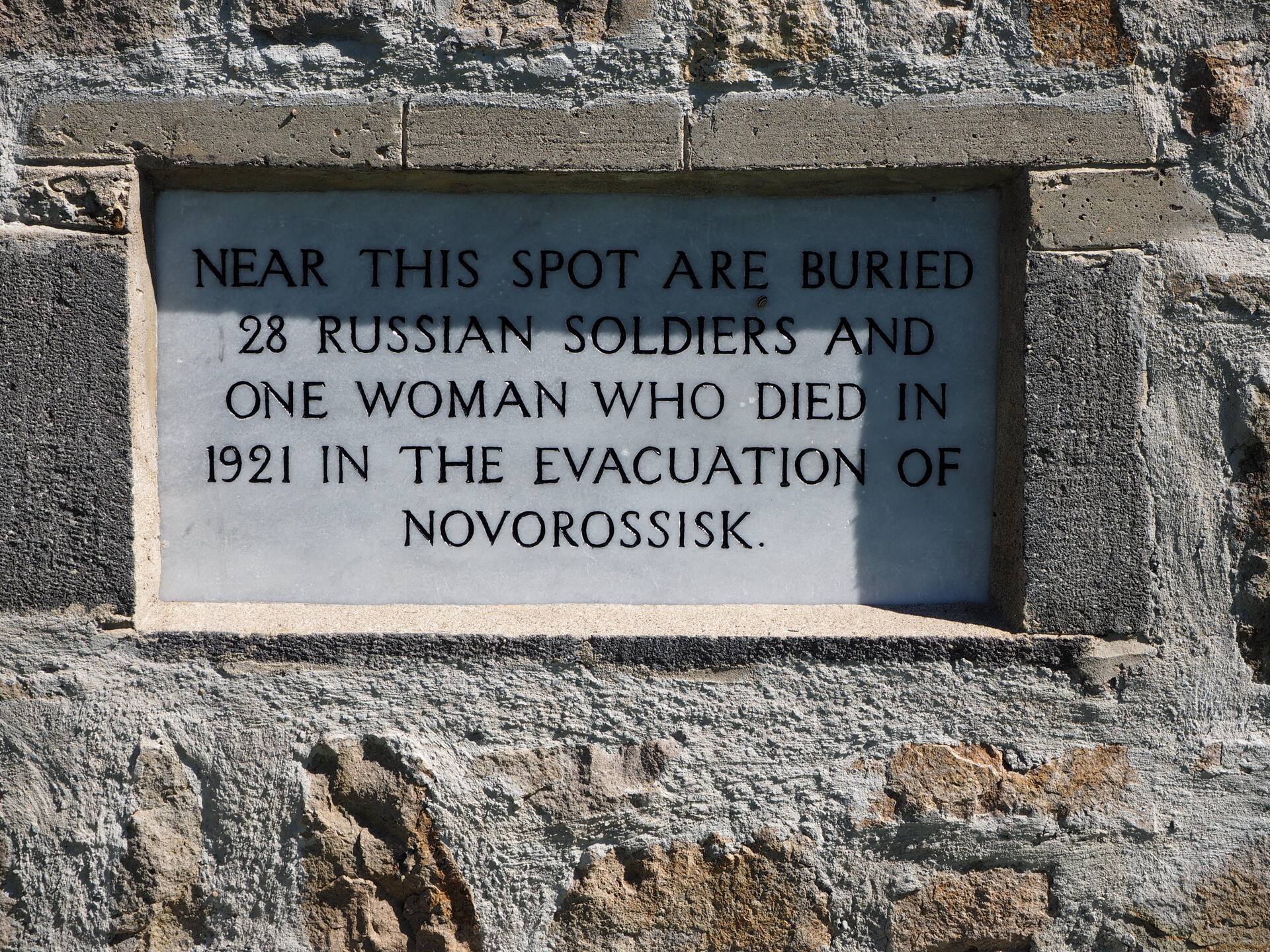

Despite this earlier experience, the French located the main Russian camp on this same exposed Peninsula. Historian Natalya Lapaeva quotes the recollections of some of the Russians who camped there, citing the rain and wind, the tearing down of tents, one writing that the “terrible wind on the rocky Limnos’s coasts was the bane of our life”, clearly echoing the views of their predecessors. Poor and insufficient rations weakened the refugees. Despite the opening of two French military hospitals to cater for the medical needs of the refugees, soon they would be filling the ground with the graves of those who succumbed. 29 were buried at the East Mudros Military Cemetery and over 350 (including 82 children) in the new cemetery established on the Peninsula.

An American Red Cross worker who came to Lemnos – Charles Davis – captured the life of the Russians on the Island at this time in a major photographic collection now held by Harvard University. These document the life of the Refugees, their camps and parades, religious services, football matches and much more. We see the civilians – women and children – amongst the many soldiers. Lapaeva and Bagni write of musical concerts being held, with Cossack folk songs being sung in chorus, educational classes being conducted, various workshops operating and bathing in the waters of Mudros Bay as Spring brought improvements to the weather. Those who were able to obtain passes from the French could visit the local villages and enjoy the hospitality of their tavernas.

David remembered his father telling him that he had visited the Russian camps on Lemnos at the invitation of the White Russian General Wrangel. Was this photograph taken during his visit or was it taken at the camps at Tuzla or Gallipoli? The photograph was comparable in size to the other photographs in George’s extensive collection. Indications were that it had been taken by George during this visit.

But was the photograph of Lemnos? I have walked the Turks Head Peninsula on many occasions, identifying the locations of the Allied camps and other infrastructure established there during the Gallipoli campaign. For many visitors to Lemnos and the Peninsula, your view is usually from the former locations of the Australian hospitals, looking north or east across the great expanse of Mudros Bay, towards Mudros town on the opposite shore. George’s photograph is not this view.

One of the important relics of the Gallipoli campaign is the navigational beacon that was erected at the end of the Turks Head Peninsula. This is not usually visited by commemorative visitors or tourists for that matter. But its significance to the campaign will soon be recognized with the erection of a small memorial to the role of the Royal Australian Navy in the campaign, an initiative based on my own research, the plaque funded by the Lemnos Gallipoli Commemorative Committee and supported by the local authorities.

It was on my most recent field trip to Lemnos that I visited the beacon and took many photographs. A few of these approximate the scene captured by George one hundred year ago. The photograph he took is indeed of Lemnos, taken from a location not far from the beacon, looking west across the Turks Head Peninsula to the mainland. The photograph not only confirms George’s presence on Lemnos but that he walked the ground where the Australian medical facilities were based during the Gallipoli campaign.

Lemnos itself would be a place of re-settlement for many Asia Minor refugees, fleeing across the waters of the northern Aegean, first to Lesvos and Chios and then on to landfall on Lemnos. Bagni writes that as the Russians began to depart, some 3,000 Greek Asia Minor refugees arrived at Lemnos in June 1921. Historian Dimitris Plantzos writes that the refugees who came to Lemnos would total 4,500, representing 20 per cent of the then population of the Island.

As someone who has researched Lemnos’ history – particularly its connection to Anzac – I am aware of the remarkable contribution made by these desperate people fleeing their homes in Asia Minor, arriving with little but their hope for a better future.

They settled across the Island, given land either on the outskirts of existing villages (such as Kontias), re-populating villages abandoned by their former Muslim residents (such as the former village of Lera, renamed by the refugees as Agios Dimitrios) or establishing new villages such as Nea Koutali on the shores of Mudros Bay. Like many Asia Minor refugees who re-settled in Greece, the latter named their new home after that which they had been forced to abandon, the small Island of Koutali in the Sea of Marmara.

Their contribution to Lemnos’ development can be seen to this day. They brought their skills in fishing and agriculture, bringing with them their distinctive cultural expressions which can be seen in the traditional dances, clothing and music that has become an essential part of modern Lemnos. These refugees would achieve great things. One of their descendents – Lee Tarlamis – is a member of the Victorian Parliament.

George’s visit to the Russian camps no doubt played a part in his development as a refugee helper and administrator, building on his already strong grounding from the Russian camps at Tuzla and the tour of those at Gallipoli. His visit to Lemnos would have added to the experience that he would later bring to the re-settlement the Asia Minor refugees in northern Greece.

Another historical speculation is whether George met some of the Asia Minor refugees that had been re-settled in the villages nearby as he headed to and from the Russian camps on Lemnos. Did he see their camps? Did they giving him inspiration for the next humanitarian effort for which he would be honoured? We don’t know but my speculation is not unreasonable.

The presence of George Treloar on Lemnos creates a new connection to the story of both Lemnos and this remarkable refugee worker. He came to see how the Russian refugees were coping on the Island. And not far away – across a small inlet – the refugees from Asia Minor would make their home. George would go on to help many more of these refugees arriving in northern Greece, an effort for which the George Treloar Memorial now stands in Ballarat.

Jim Claven is a historian with degrees, a features writer and author, his most recently publications include Lemnos & Gallipoli Revealed and Grecian Adventure. He is a member of the George Treloar Memorial Committee, and worked on the creation of the George Treloar Memorial in Ballarat. The author acknowledges the contribution of George Treloar’s son, David Treloar, in the preparation of this article. David is currently finalizing a major new publication on his father’s refugee work in Greece. Those seeking more information on the Russian presence on Lemnos are referred to the work of historians Bruno Bagni, Natalya Lapaeva, Dimitris Plantzos and Paul Robinson.