Four years ago, Greek-American journalist and academic Dr. Mary Cardaras embarked on a personal journey, one which saw her through states of loss, discovery and renewal.

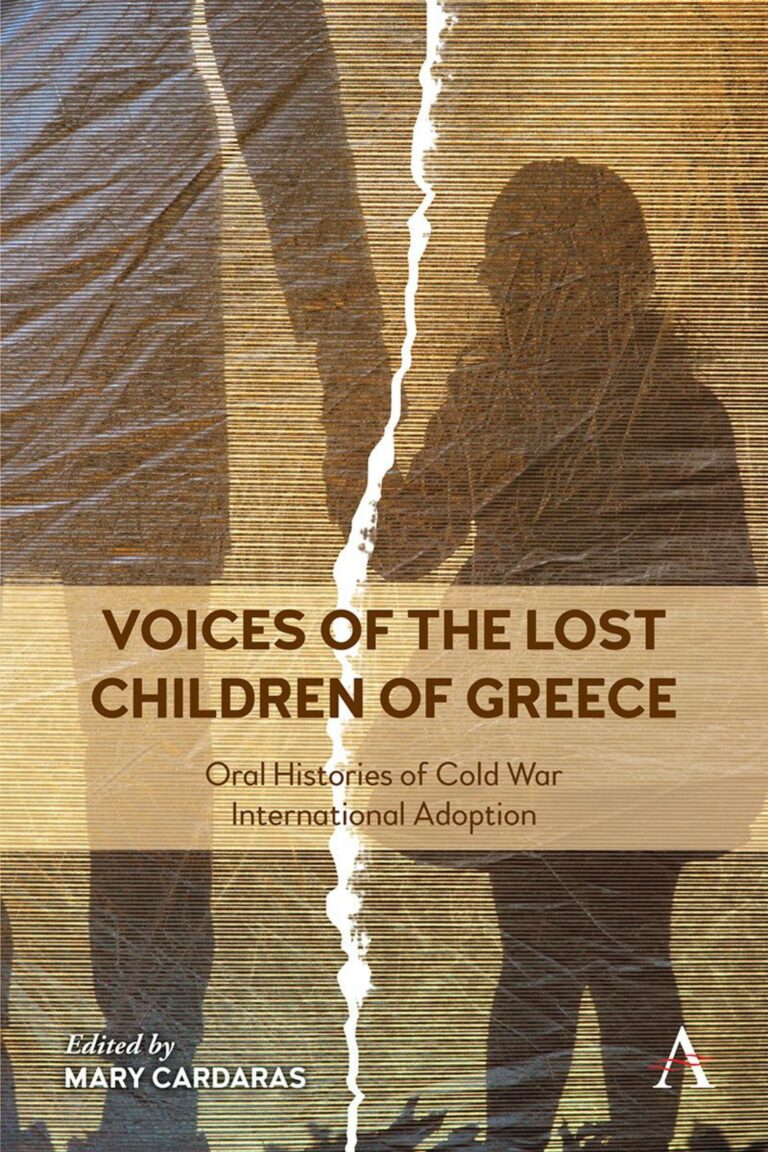

‘Voices of the Lost Children of Greece: Oral Histories of Cold War International Adoption’ edited by Mary, is a collection of 14 essays written by American and Dutch adoptees born in Greece.

But this work is just the penultimate chapter of a story that began much, much earlier; the day of her birth.

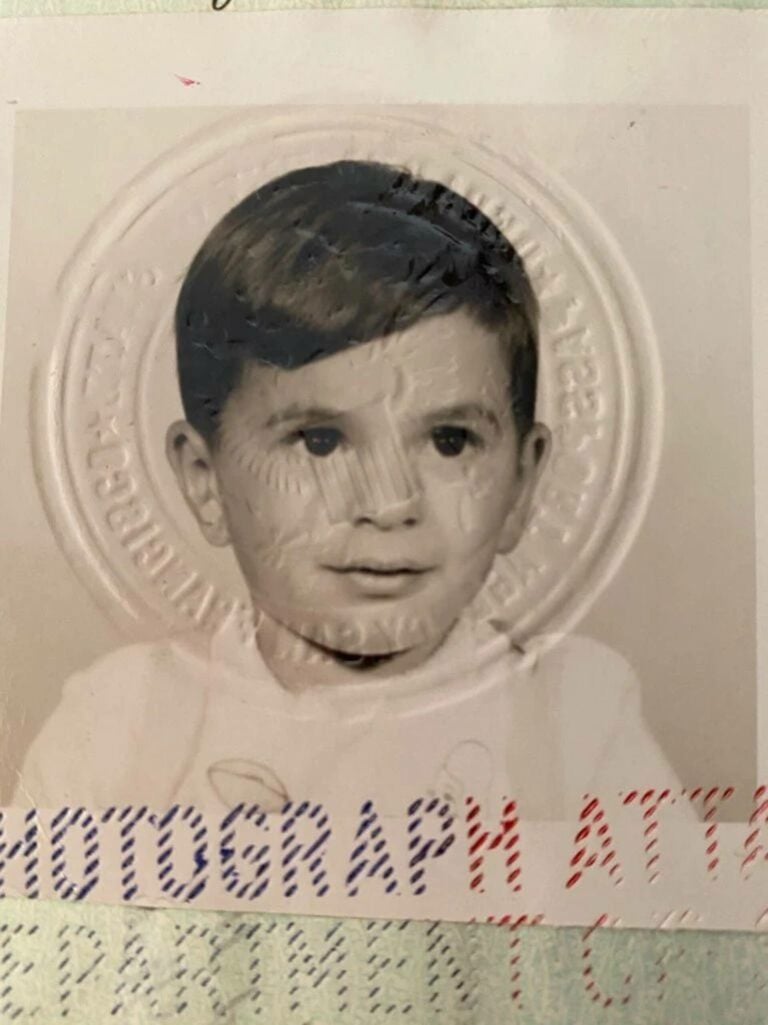

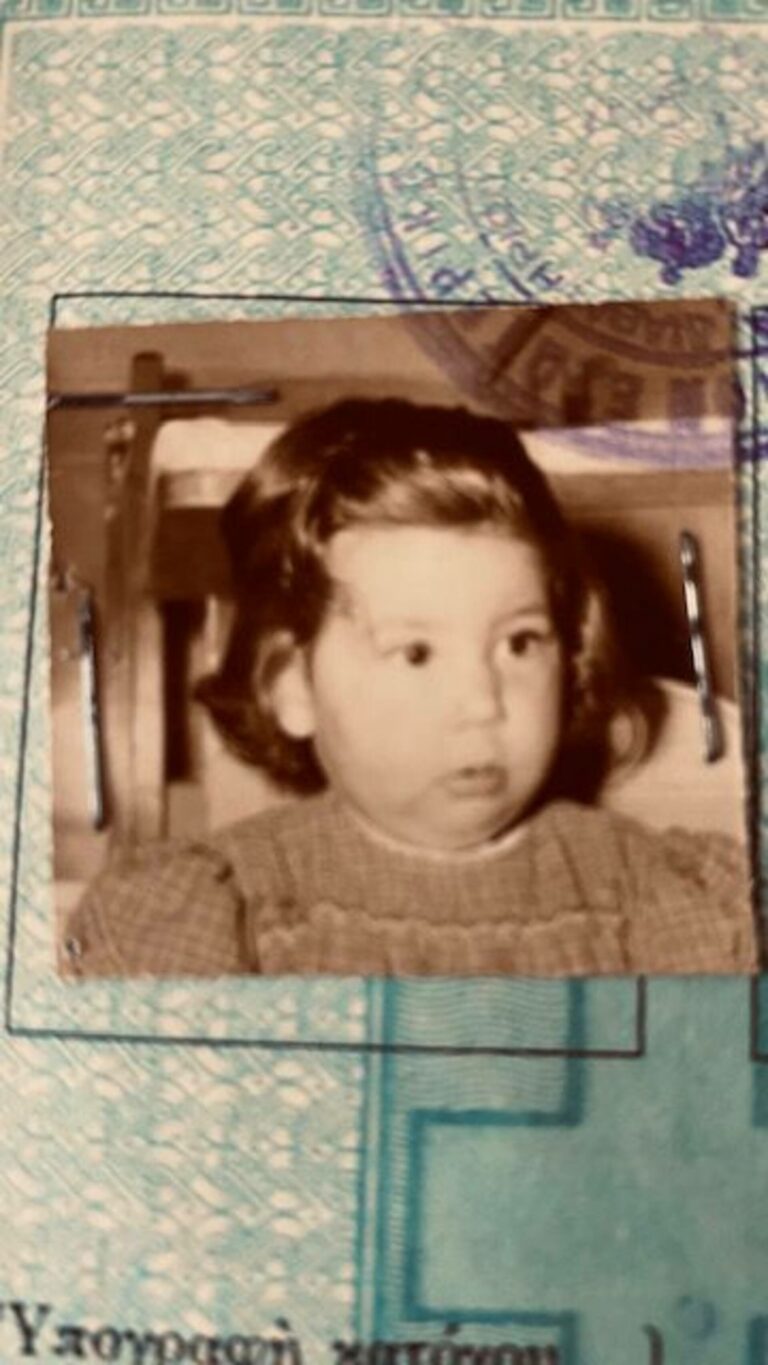

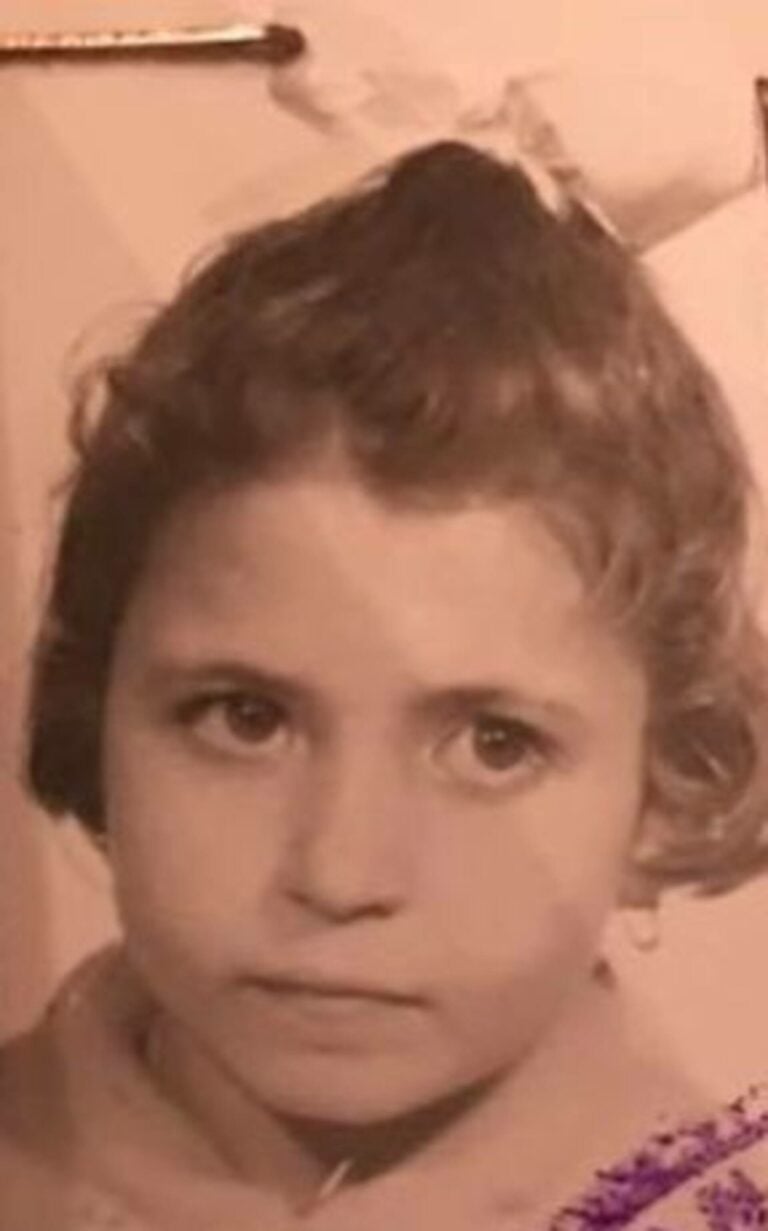

On 2 January 1955 Mary was born at the Athens Maternity Hospital… she only spent the first nine days of her life with her birthmother.

The country was still reeling from two unspeakably devastating conflicts, the Second World War; the Greek Civil War.

“She took me to the municipal orphanage and signed me in, after that, I became baby No. 44488.”

“I’ve known I was adopted since I was very young, while I did quietly pursue my beginnings earlier in life, it was never in a concerted way,” she tells Neos Kosmos.

“As an adoptee you never want to disappoint your adoptive parents, who were also Greek by the way and very, very good to me.”

In 2018, Mary’s adoptive mother passed away.

“I don’t think I’d ever felt such grief in my life, I was crestfallen, lost, with a sense of abandonment; I became untethered,” she explains.

Then 63-years-old, she sought solace through reengaging with her Greek identity.

“After my mother’s funeral I went back to Greek school, I started going to church again… I immersed myself in my ethnicity, it was almost like a cocoon of sorts.”

It was at Greek school that Mary met a woman named Kathy, whose cousin Dena Poulias had an incredible story.

It was the story of a baby stolen from Greece.

“It left me flabbergasted, heartbroken beyond words. I asked Kathy if she could get me in touch with her cousin, as a writer, I needed to hear her story,” she says.

Over the next year, as Mary drafted Dena’s story, while conducting interviews, she came across a book written by Belgian-American linguist Gonda Van Steen.

‘Adoption, Memory, and Cold War Greece: Kid Pro Quo?’, an account of the postwar adoption networks that placed over 3,000 Greek children with families in the United States, and more than 500 in the Netherlands.

According to Van Steen “by 1950, one of every eight Greek children were orphaned, for a total of 339,913 […] some 36,000 children had lost both parents.”

The author elaborates that in the wake of the wars “mass overseas adoptions of Greek-born children became not only possible but, according to many, necessary, even inevitable.”

The words came at Mary like revelations, she asked herself “my god, was I one of these babies?”

She was.

The first chapter in this saga ended when Mary published “Ripped at the Root”, a recounting of Dena Poulias’ lifelong mission to discover her origins.

But of course, it didn’t stop there.

Her research had led her to read Gabrielle Glaser’s ‘American Baby’.

It laid bare how the philanthropic enterprise of adoption, could be (was, and still is) corrupted to exploit the very people it purported to aid in their most vulnerable hour.

“Through all I’d learned, I had an awakening in my own life… I soon found I’d become an activist in this fight.”

Mary says that eventually time will run out for her and her fellow adoptees to discover their roots.

“We’re trying to move the needle with the Government of Greece. It’s time we put this ugly chapter of history behind us for good,” she makes clear.

“We want our adoption records opened, we want to know where we came from, and for those who were stripped of it; we want our Hellenic citizenship back.”

And in her view, it’s critical the truth of these adoptions comes to light.

“Here we have a systematic process: a devastated country, its people literally starving and dying in the streets. Orphaned children were adopted yes, but others came from parents who under the circumstances, really had no other choice,” Mary says.

“And a huge demand for healthy, white children in the USA. These children became commodities; they were brokered.”

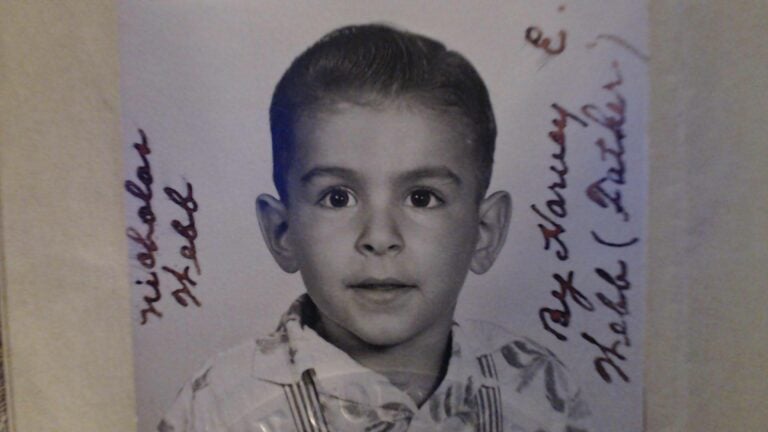

Children like Marinos, named Robert by his adoptive parents; a Greek orphan raised Jewish in New York City, separated from his brother at birth.

Or David, birthname Pavlos; his birthmother wrote him letters all his life, hoping that some day he’d return to her.

And Sonia, whose biological mother suffered from an illness her adoptive parents feared might touch her too.

Mary Cardaras didn’t get the chance to reunite with her birthmother, bureaucracy stood in the way. She passed in 2020.

“But I did meet her caretaker last summer, I’ve visited her grave… I met her friends and the people who loved her.”

Now at 68, she hopes to reunite with her father, she has his name, she says there’s a good chance he’s still alive.

“Many of the people I spoke with, who told me their stories and penned essays for this book, they’ve had wonderful reunions, they’ve found a part of themselves which could have otherwise remained lost.”

But still, there are others who can’t trace their roots, who know who they are but not who they once were.

And that Mary says, is why the battle goes on: the adoption records must be opened.

She’s calling on the Hellenic Republic to act and help repatriate these lost children, a call she’s addressed to Greece’s Prime Minister directly via Twitter.

“Will the Parthenon Marbles return home before us?”