Last Monday, on the eve of Anzac Day, the Melbourne Holocaust Museum presented a lecture by visiting historian Dr Leon Saltiel on commemoration of the 80th year of the deportation and extermination of the Greek Jews of Salonica, or Thessaloniki by the Nazis.

Dr Saltiel has dedicated his life to studying the Nazi persecution of Jews in Greece, especially the Sephardic Jews of Thessaloniki.

His book “The Holocaust in: Reactions to the Anti-Jewish Persecution, 1942–1943,” won the 2021 Yad Vashem International Book Prize for Holocaust Research. His book, “Do Not Forget Me: Three Jewish Mothers Write to their Sons from the Thessaloniki Ghetto,” details how the Nazis began persecuting the country’s Jews, starting with small indignities, and culminating in mass imprisonment and deportations.

Over 80 percent of Thessaloniki’s Jews perished

In 1941, just under 70,000 Greek Jews were in Greece and now “less than 7000 remain” says Dr Saltiel. Up to 50,000 Jews from Thessaloniki were sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing centre. At Birkenau, the SS murdered virtually all the Salonika Jews upon arrival.

Talking to Neos Kosmos, Dr Saltiel said that the Sephardic Jews in Salonika had a different position compared to the Romaniote Jews, who had been in Greece since antiquity and had become more entrenched in parts of Greece.

“They [Sephardic Jews] weren’t as embedded in Hellenism or evidently as others.”

On October 28, 1940, fascist Italy invaded Greece from Albania. However, the Greek army drove the Italians back into the Albanian mountains. To secure the Balkan flank for an imminent invasion of the Soviet Union, Hitler ordered the invasion of former Yugoslavia and Greece. On April 6, 1941, the Germans, Italians, Bulgarians, and Hungarians attacked. By April 28, Axis troops had occupied most of the Greek mainland, but Greek resistance on the islands continued until June.

The Jews of Thessaloniki were Sephardim from Spain who found safety in the Ottoman Empire after their expulsion during the Inquisition.

“They were often identified by their accent, born of a mixture of Spanish, Hebrew, Turkish, and Greek. This accent made them seem alien to some,” says Dr Saltiel.

Although there was major resistance to the Nazis, the Nazis always sought allies in every place they occupied, including Greece.

“Greece had three puppet governments during the occupation and even developed a paramilitary that worked with the Nazis.”

Death camps and Resistance

In July 1942, German military authorities deployed 2,000 male Jews on forced-labour projects in Salonika.

In February 1943, the Germans concentrated the Jews of Thessaloniki in two enclosed ghetto-like areas of the city.

Italians were the only occupiers who largely protected Jews in their occupation zone in Greece. The Bulgarians and Hungarians were often willing accomplices to the Nazis’ desire to exterminate the Jews.

But after Italy surrendered to the Allies in 1943, the Germans took control and implemented the “Final Solution” in all of Greece.

Between March 20 and August 19, German officials deported over 50,000 Jews from Salonika to the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing centre. At Birkenau, the SS murdered virtually all the Salonika Jews upon arrival.

Dr Saltiel says that that “many Greek Jews joined the [EAM ELAS] Resistance, which was communist led.”

The historian points to the fact that the Nazis rounded up Jews in Thessaloniki in 1943, just as the Resistance was starting. Whereas in Volos and Larisa the persecutions began in 1944 “and the resistance was better organised.”

“Jews played a significant role in the resistance as Greeks, not as a separate resistance as in Poland.”

Often Greek Jews in the Resistance “created pseudonyms so it was very difficult after the occupation and after the Greek Civil War to determine who was Jewish and who wasn’t.”

Greek Jews did not speak Yiddish, so the German concentration camp guards could not understand them and gave them the worst details, of cleaning the incineration ovens. Greek Jews led one of the few uprisings in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

“Some escaped and even killed a few guards, but overall, it was futile exercise as most were exterminated,” he says.

As Greece fell into successive right-wing governments, after the war, and the bloody Civil War between left and right in 1945-1949, and many Jews did not want to “come out” as former Resistance fighters. It wasn’t until the 1980s with the Papandreou led PASOK government, that the Resistance was recognised.

Antisemitism in Greece is difficult to define

Antisemitism in Greece according to Dr Saltiel “is difficult to define” and changes from place to place.

“There were different patterns of how Jews were seen or treated in Greece, and those patterns reflected different areas and histories in Greece.”

What is evident says the historian, was that antisemitism in Greece differed from Germany and other parts of Europe. “There was no racialise aspect to Greek anti Semitism, like in Germany.”

“In Greece, there was no racial aspect to anti-Semitism, Greek Christians and Jews did not see themselves as racially different, much of the anti-Semitism was largely based on the historic Greek Orthodox Church’s view that the Jews killed Christ.”

He points to how in Sydney Archbishop Makarios who made clear that antisemitism was not welcome and called it a dark chapter in Greece’s modern history.

Dr Saltiel stressed “economic opportunism,” rather than antisemitism in Thessaloniki.

“Economic opportunity played a factor and many properties once owned by Greek Jews ended up the hands of local Greeks.”

Greece was a poor Balkan nation where the Jews occupied similar occupational and class position as non-Jewish Greeks.

Dr Saltiel makes a distinction of the “different patterns and in different regions” of Greek antisemitism.

While the Romaniote Jews had a “more secure Hellenic identity” Dr Saltiel says “what is clear, though, is that the Romaniote Jews also suffered tremendously.”

“Romaniotes in Athens had a more secure Greek identity and were less evident, they were not seen as other, whereas Sephardic Jews were always other mainly because of their accent.”

Dr Saltiel says “it is not the sort of antisemitism that was evident in parts of Europe, and still is.”

“You have still a form of that kafenion (coffeehouse) anti-Semitism where discussions occur about conspiratorial nature of Jews and this is benign compared to the antisemitism that was, and is experienced in other parts of the world,” Dr Saltiel says.

He points to the 2008-2017 Greek Financial Crisis “where Jews particularly for the right wing became a focus.”

According to Dr Saltiel the Greek left’s general anti-Israel attitude in the 70s and 80s, “often veered into anti-Semitism, whereby anti US, anti-Israel attitude flipped over into anti-Semitism.”

“There is nothing wrong with criticising Israel, and Israel’s governments, but often you’ll find the criticism provides a certain cloak for anti-Semitism.”

He says that in the 1990s, in the 2000s, as the conflict between Israel and Palestinians escalated.

“You’d often see Greek newspaper cartoons of Israeli soldiers depicted as Nazis and Palestinians as Jews, which is profoundly wrong.”

“One can criticise Israel and its defence forces, but IDF are not Nazis and Palestinians are not being driven into gas chambers.”

Greece and Israel a complex relationship that’s now closer than ever

Dr Leon Saltiel is positive over how Greece in the last ten years had sought to actively combat antisemitism. “Things have changed tremendously and that the relationship between Israel and Greece is unprecedented in terms of its robustness and its closeness now.”

“There is incredible exchanges and investment between Greece and Israel in areas of economics, science, military and culture.”

There are “more Jews returning, particularly from Israel that may have had Greek ancestry, however at the height there were at least 65,000 Jews before the Holocaust.”

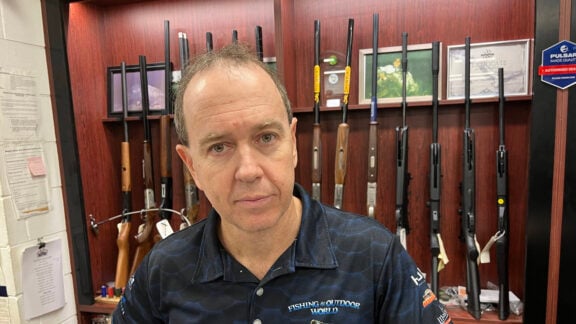

Dr Saltiel is a member of the Central Board of Jewish Communities of Greece and of the Greek delegation to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. He now lives in Geneva where he serves as Director of Diplomacy, Representative at UN Geneva and UNESCO, and Coordinator on Countering Antisemitism for the World Jewish Congress.