On September 6, U.S. Senator Tommy Tuberville (Alabama) appeared on Fox News complaining about the condition of the United States military, opining that “We are so woke in the military that we are losing recruits right and left” and then providing as an illustration of “wokeness” that “We have people doing poems on aircraft carriers over loudspeakers.”

Notwithstanding a lack of eloquence that could use a little poetry itself, there’s more at stake in Senator Tuberville’s attack on the U.S. Armed forces than fear about sonnets for shipmates. Recently the Secretary of the Navy, Carlos Del Toro, criticized Tuberville for blocking military nominations over the Pentagon’s abortion policies. Tuberville met Del Toro’s suggestion that he is aiding and abetting U.S. enemies by undermining military preparedness by continuing to try to score points for political gain.

Tuberville’s attack on poetry could be simply dismissed as a feature of our political madness, of a conservative party that has exploited misogyny and attacked reproductive rights as part of a multigenerational electoral strategy. In this vein, the right wing’s “woke panic” is merely a brand update for the 21st century.

But I think Tuberville’s comments both misrepresent the functions of poetry and song in the military traditionally and also reveal what he and his colleagues really want out of the U.S. population.

Citizens and Soldiers

One of the curious things about Tuberville’s comments is that there is a tradition among conservative thinkers (for instance, Victor Davis Hanson) of praising ancient Greece for its citizen soldiers. Indeed, a great deal of the emphasis on ‘classical learning’ among the conservatives emerges from a widely held belief that the strength of ancient and modern democracies relies on educated and enfranchised soldiers.

Poetry and song were essential parts of education in ancient Greece. Some of Greece’s most famous thinkers, however, may have had some sympathy for Tuberville’s comments. In the Laws Plato (630) praises poets–to a limit–like Theognis and Tyrtaeus for emphasizing certain qualities, like courage, and loyalty. But when Plato’s Socrates sketches out his ideal Republic, he takes pains to ensure that they have training in music and storytelling so they can “safeguard” the state against “corruption” (4.424).

Poets and traditions of song were important to war in antiquity, or at least to shaping the way audiences think about it. The martial poetry of Tyrtaeus and Callinus, for example, encourage people to stand and fight for their country. Tyrtaeus sings that “it is shameful to see a body lying in the dust / driven through, a spear sticking out of its back” (fr. 11) and Callinus warns that no one misses a man who runs away and dies in shame, but a whole country will “long for a courageous person / when they’re gone, someone the worth of living heroes” (fr. 1).

Exhortations for war were allegedly popular among the Spartans, a people whose historical prowess in war–exaggerated to the extreme–is a popular topic in many conservative circles. But they didn’t love all poetry. They were famous for allegedly banning the poet Archilochus from their lands.

The Roman Valerius Maximus suggests that the Spartans found Archilochus’ poetry immodest; but according to Plutarch, the Spartans exiled Archilochus for cowardice.

He used the same language as Tyrtaeus and Callinus to sing about abandoning his shield, insisting “I rescued myself. What does the shield matter to me? / Screw it. I’ll buy another one that’s no worse” (fr. 5).

Unintended Lessons and Reflecting on War

Poetry and art have long been useful to soldiers, veterans, and the communities impacted by violence to commemorate, preserve, and reflect on what they have experienced.

But poetry can be a slippery thing–the martial ideals explored and advanced by a Callinus or Tyrtaeus are just as easily subverted by someone like Archilochus who makes a joke of the ancient Spartan saying attributed to a mother for her son, “come home with “this shield or on it” (Plutarch, Spartan Sayings 241f). The Spartan desire to control poetry may share kinship with Tuberville’s poetry blaring navy.

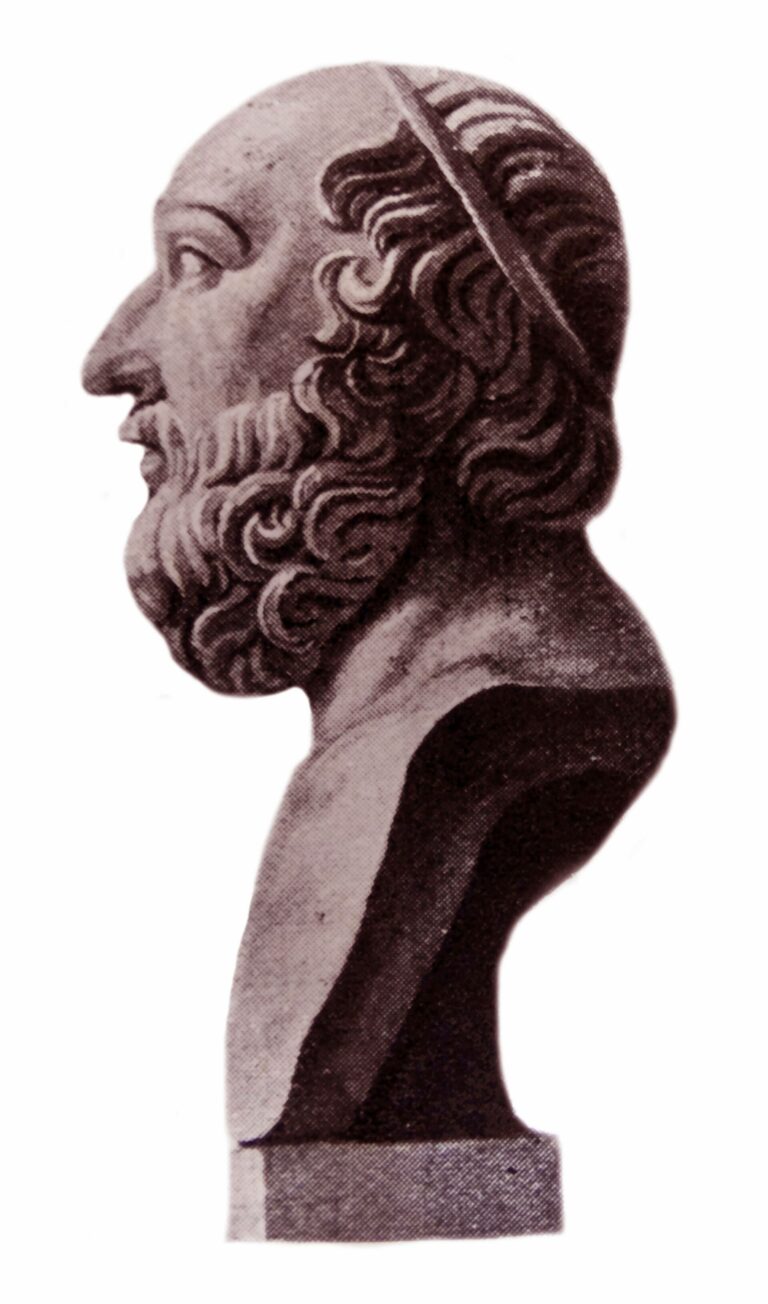

What’s the danger of a woke warrior? Homeric poetry is at times rather popular with certain crowds for its heroic masculinity and its exploration of war. But at the center of the Iliad is a heroic figure who changes his mind. When we see Achilles in book 9 of the epic, he is “delighting his heart on a lyre, singing the famous stories of men”.

Many Homerists think this scene depicts Achilles going through the stories he knows about the past and trying to figure out what he should do next.

At this point in the epic, Achilles has withdrawn from fighting over a conflict with Agamemnon. During his reflection, Achilles decides first that risking his life–even knowing he will cut it short–isn’t worth either the future glory he is promised nor the ‘honors’ he receives while alive.

He decides by the end of book 9 that he will stay only to protect his own ships, if he stays at all. But we learn through the action of the epic itself that he should have fought to defend the life of his friends. Achilles’ wish that the Greeks will suffer so that they will understand that dishonoring him is wrong eventually leads to the death of his closest friend (and likely lover) Patroclus.

The Iliad is a complex poem with many different messages. At its core, it helps audiences think about the cost of violence and the meaning of war. Ultimately, I think it suggests that the only true reason to fight is to protect the people you love, whether that means your family, your citizens, or the people standing next to you in the trenches. Surely, this is not a bad lesson for any warrior today.

Players and Games

In response to Senator Tuberville’s comments, Representative Ted Lieu, a member of the U.S. Congress and a veteran of the Air Force, tweeted: “Sen Tuberville never served, so he may not understand there is downtime in the military. Some personnel may watch movies, some play cards, some write poems. That’s normal.”

Our soldiers, sailors, and airmen are human beings. (Disclosure: My wife, along with many members of my family are veterans of the U.S. Army.) They have lives and families and make meaning of the world like the rest of us.

And they are better soldiers and citizens if they have the frameworks to ask questions of themselves and their world provided by literature and art.

But I suspect that the truth is that Senator Tuberville and people like him don’t really care about the soldiers at all. Tuberville does not want informed, citizen soldiers. He wants faceless drones who follow orders without questions. He wants spectacular fireworks and flyovers for football games. A better ancient comparison for what he’s looking for are the helots who were dominated and enslaved by the ancient Spartans.

Those outside of the U.S. may not know that before he was a Senator from Alabama, Tommy Tuberville was a college football coach. Division 1 Football in the U.S. exploits and then spits out athletes, creating glory and profit only for a few, but especially for their coaches.

Tuberville wants from U.S. enlisted military personnel what he had as a college football coach: an uneducated, powerless workforce he can exploit for his own ends.

Just like the U.S. military, college football teams are largely made up of minoritized groups who see the army or athletics as a way out of poverty and the very racist structures that created that poverty to begin with. Politicians like Tommy Tuberville don’t want soldiers and students educated in poetry and the arts because they don’t think they are worthy of it.

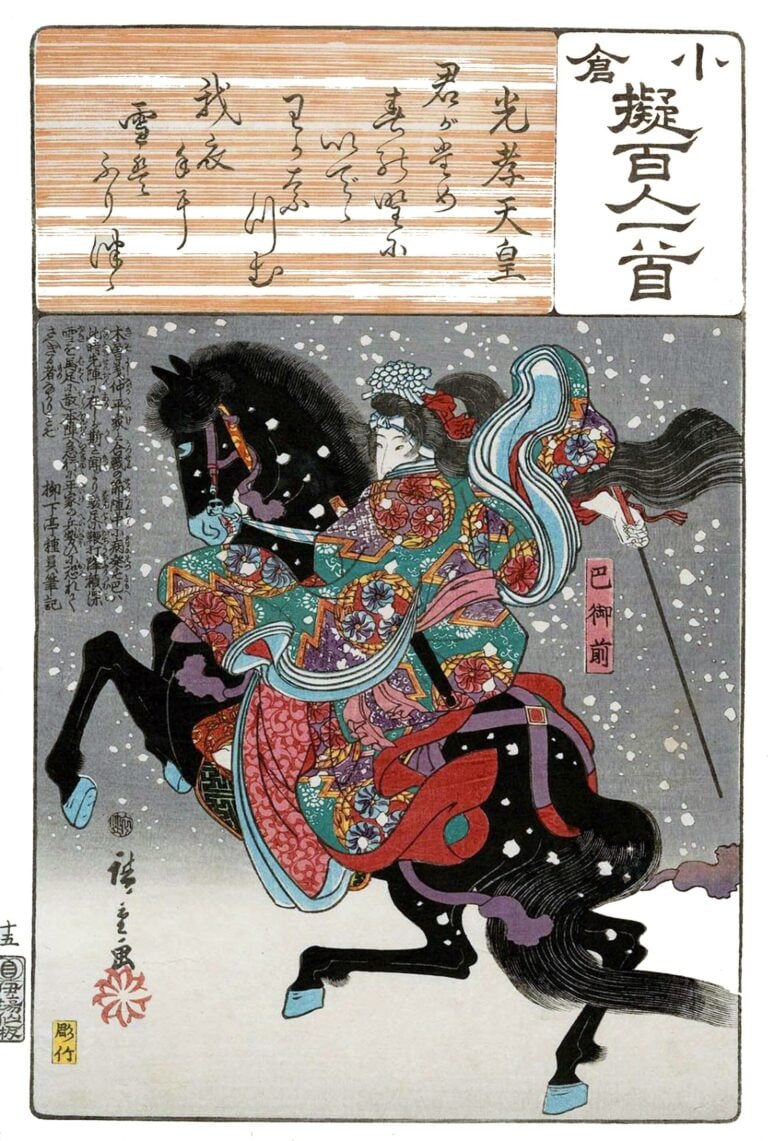

Interestingly poetry and warcraft have been enmeshed since antiquity to modernity, Miklós Zrínyi (1620-1664) was a major Croatian and Hungarian military leader, statesman and poet, the female samurai, Tomoe-gozen in the 11th Century whose love was the Genji General Kiso Yoshinaka, has had major poetry written about her such as, ‘The Tale of Heike’.

Banning poetry from an aircraft carrier isn’t about preventing soldiers from being ‘woke’. It is part of a larger conservative blueprint to preserve the liberal arts for an elite few and provide only ‘practical’ or vocational training to everyone else. Tuberville and his ilk want people to get in line and do a very specific job until they’re worn out and can be replaced by the next man standing. Reading a poem just might let people believe that, like Achilles, they have choices in the lives they live.

Joel Christensen is Professor and Senior Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs at Brandeis University. He has published extensively and some of his work include Homer’s Thebes (2019) and A Commentary on the Homeric Battle of Frogs and Mice (2018). In 2020, he published The Many-Minded Man: the Odyssey, Psychology, and the Therapy of Epic with Cornell University Press.