Marrickville, Earlwood and Parramatta constituted what once were Sydney’s Hellenic hubs, where many post-war Greek immigrants settled during the mass chain migration between 1957 and 1975. However, these once working-class areas have now been gentrified and have become hip hubs. Property prices in Marrickville hover from around $2 million for a house and $800,000 for a unit.

Greeks wanting to escape from inner city working class areas like Marrickville in the 1970s opted for the newly built metro suburbs in the west. They chased the Australian Dream of a quarter-acre block, for those few unable to make it out are now sitting on multimillion-dollar homes.

Maroubra, by the coast, became a gateway to eastern suburbs close to the beach. Greeks, like the demographic in the area at the time, were working-class. It is still one of Australia’s most multicultural suburbs. It is home to people of 133 different cultural and linguistic groups, according to the ABS 2021 Census. For realtors, Maroubra is the new Eldorado, the area is caressed by Sydney’s emerald beaches, and is only 10 km from the CBD. The local beaches once ruled by surf gangs like the Bra Boys, notorious for violence and alleged links to organised crime, are now the most prized attribute for new, well-off investors.

Two of its few remaining post-war Greek migrant residents say the neighbourhood feel is still not lost. Not for them, at least. Whether for an over-the-fence chat or a visit, 90-year-old Aliki Coroneos catches up with next-door neighbour Maria Spathis, 72, daily.

“We made friends from the moment they moved in next door. I was fortunate to have met her,” Ms Coroneos, a Maroubra resident since 1968, tells Neos Kosmos.

“Our families sort of grew up together.”

Spathis, 72, says the community on their street is a “close-knit one”.

“We all know each other. But with Aliki, it’s more than that. We have a special bond and developed a strong friendship.

For, Cosmos Coroneos, Aliki’s son, it was the interplay between Aussie-style privacy and an openness typical of the Greek temperament that gave way to a neighbourhood life with the “best of both worlds”, as he recalls.

“We had Anglo-Australian neighbours at the back, and we got along well.

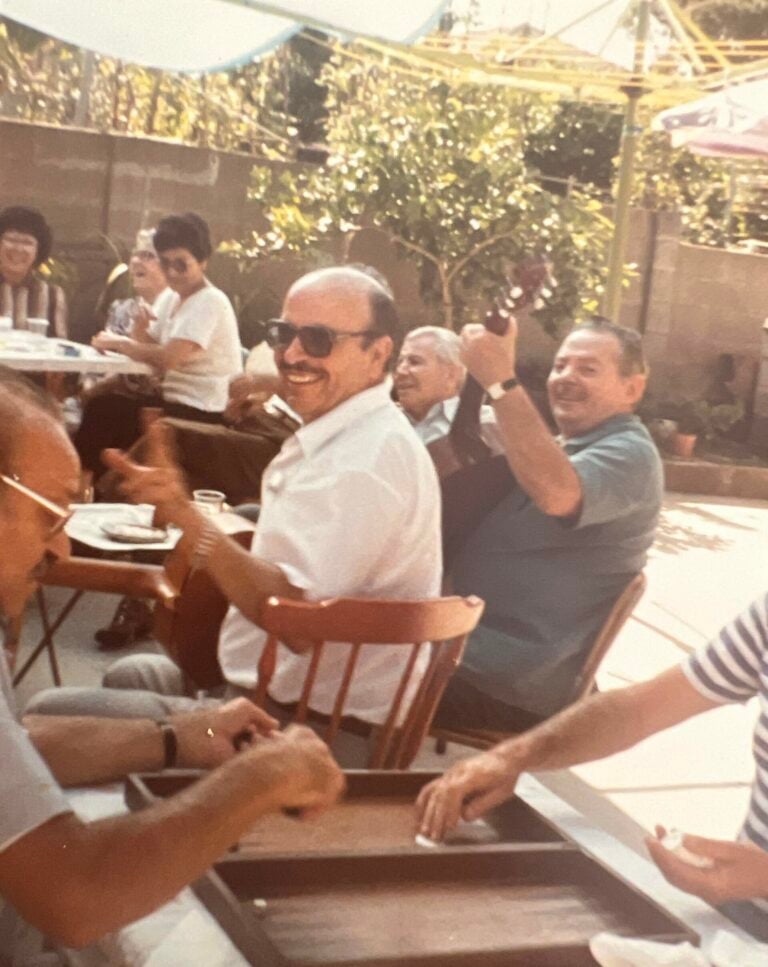

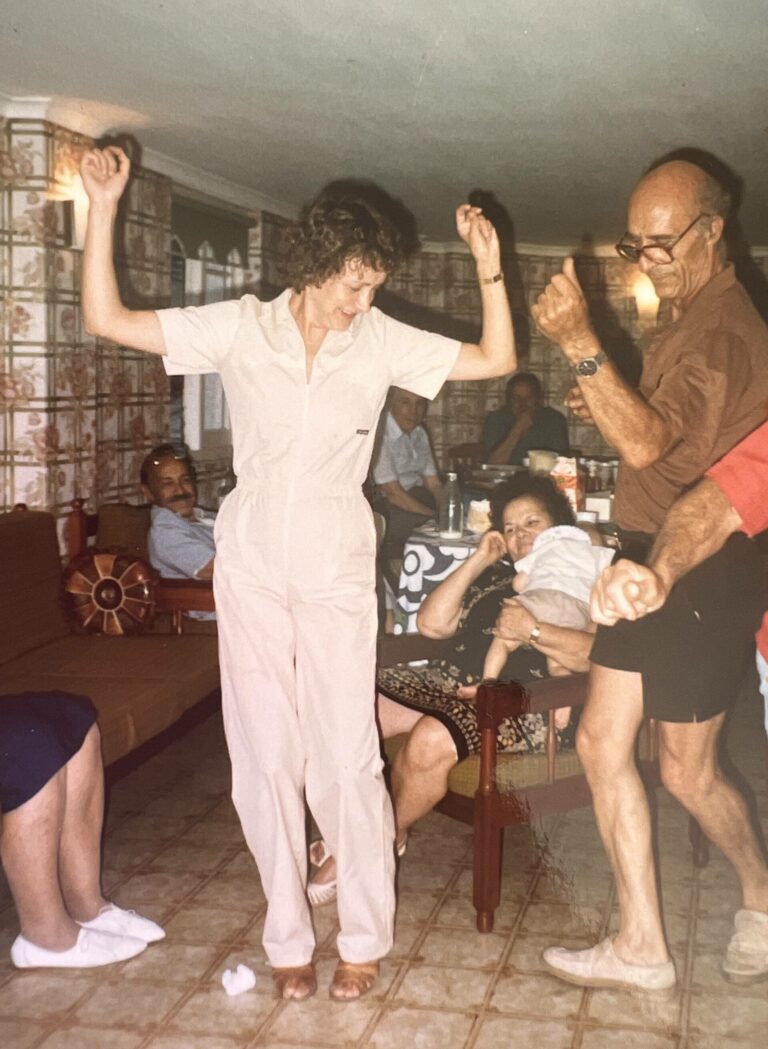

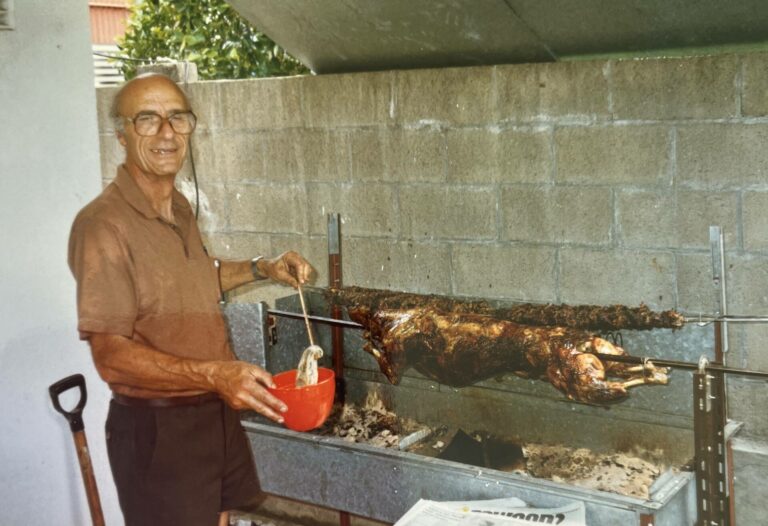

“There was a lot of tolerance. That thing when someone’s shouting, and you know it doesn’t mean they’re angry; they’re just happy or excited. “Noise in the neighbourhood was part of life, and being Greek… you know, we’re not very quiet people,” he laughs.

“John [Maria’s late husband] was an electrician, and dad was a Jack of all trades, a mechanic type person, so any time something needed fixing, John would come over and vice versa

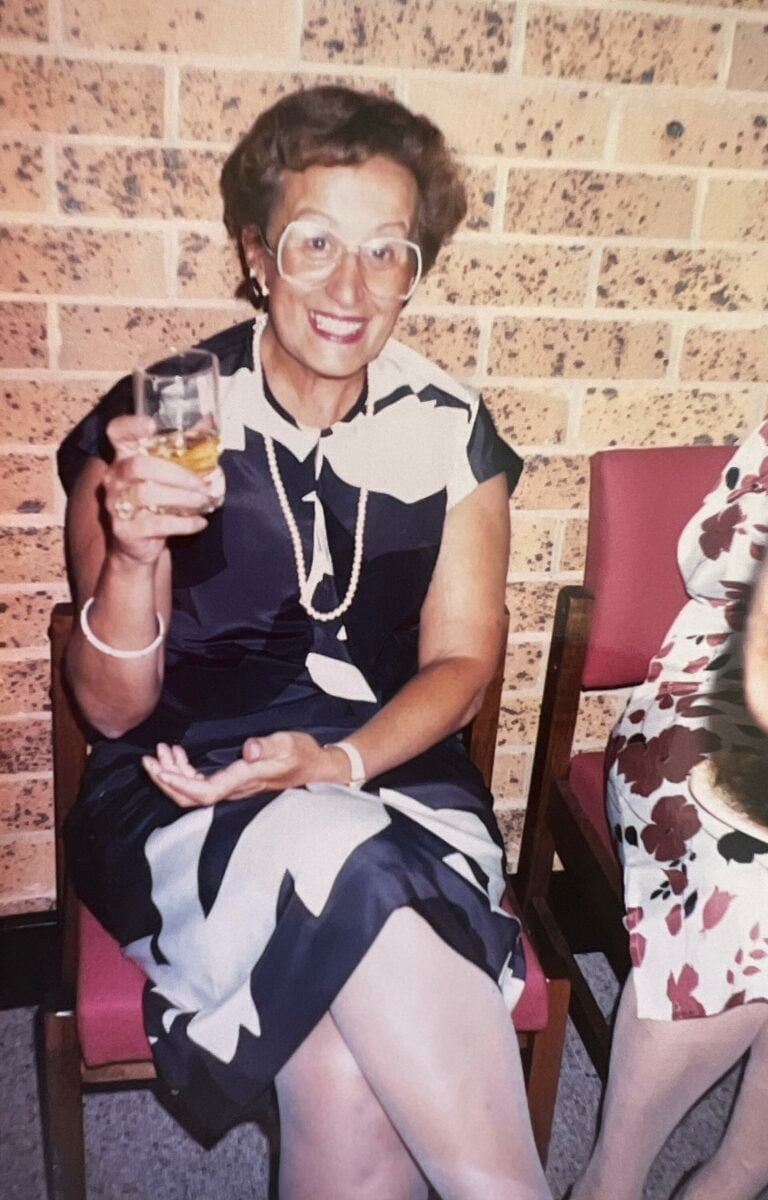

Aliki Coroneos remembers their gatherings at home with friends.

“We were still new here, so the Greek element was alive and with us. Thinking about it now that I’ve grown older, we were the noisy ones.

“I’m surprised we never got a complaint with all the parties we’d have and everyone singing. They [neighbours] were probably enjoying our Greek music!”

Socialising for the younger second-generation Greek Australians was different back then, Coroneos reflects.

“George, from next door, and I would go out on the road to play tennis, and then suddenly, we had ten kids waiting their turn. The young kids would be on the lookout for cars.

“We used to do a lot with the neighbourhood kids, and that’s how parents met each other. That’s all gone. I was talking to Maria [Spathis] about it the other day. I said, ‘Here’s not as many kids around’, and she said, ”Actually, more kids are living on the street than ever; it’s just that they never go out; they stay indoors’.”

Since migrating with her parents at seven, Maria Spathis moved to Darwin, then regional New South Wales, before settling in Sydney.

“I’m very happy; my life was full of adventures, and I overcame many obstacles to get where I am today,” she says.

Spathis became a school teacher despite not having the help from her parents that most kids today take for granted.

“I relied a lot on myself; my parents were both working, never learnt English, and we had no relatives here, so I had to make my own decisions.

“It was different back then,” she says, and talks about frequent police raids at night in Woolloomooloo, when they chased Greek and other migrants who would jump ship and sneak into Australia illegally.

“Wooloomooloo is trendy now. Back then, before the amnesty [when the Department of Immigration sought to regulate the status of people who had overstayed their visas], many people would arrive illegally. You had the palikaria jumping from fence to fence in between houses during the police raids.”

Fence-jumping also applied to prospective partners not approved by parents, Spathis laughs.

“Hanging out with non-Greeks was a no-no, and it wasn’t enough for your prospective husband to be from Greece; they had to be from the same place [in Greece].”

As a Patmos native, convincing her parents to accept her prospective husband, John, a Lemnian, was “a big problem”.

“Interesting times,” she adds.

“We met at a brotherhood [dance] ball and had to hide for a while. Eventually, my parents accepted it.”

In 1969, Maria moved into Maroubra with John, her husband, with her in-laws living on a different floor of the same house.

It has been the family’s home ever since. Spathis’ granddaughter, named after her as Maria, is the fourth-generation inhabitant.

“All those eastern suburbs then Paddington, Surry Hills, were bustling with Greeks, Italians and Maltese.

“In our street, every second house belonged to Greeks, but as years passed, many passed away, and their children sold the properties.”

The Spathis family bought their house for $25,000. Now, it could fetch over $2 million when the median price for a home in Maroubra is $2.3 million.

“Back then, my husband’s salary was $36 a week. He was also doing taxi shifts three times a week so we could get by. With my salary – which was smaller, because as women we earned less, around $50-60 per week.”

The Coroneos family bought their house for around $20,000. He does the maths; “I think my parents earned about $3,000 a year; they had to save six – seven times their annual salary, and that’s not the case anymore if you want to buy a house here.”

Demographics have changed significantly he says, “Back then, they would call us the Maroubra Continentals.”

“When we arrived here, it was mainly Anglos, then more Greeks came, Italians, Indonesians, Chinese and now French. There’s a French school directly and also many Jewish, there’s a Synagogue and a Jewish school nearby.

“It was always a lower–middle–class area; now it’s gotten much richer.” The tendency for many nowadays is to sell or rebuild, he says.

“Like the house across the road, they knocked it down and made two townhouses.”

That’s not the plan for the Coroneos and the Spathis families.

“We like it here; we know the area. We’re close to the city, close to the beach. Sell it and go where? It’s not easy to buy even a smaller house here anymore,” Spathis says.

“Aliki also has her son and daughter who take turns staying in the house with her. We’re the oldest residents in our street now; I don’t see many other families being that close with their children.

“Here, I can be with my daughter and granddaughter, and I’m close to my son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren. Leave and be away from family? There’s no point.”