Forty days ago, Chrisoula Tsopanis (nee Pappas), Chrissy to all of us, died at the fulsome age of 94.

I want to mark those 40 days with a homage to one of the more important influences in my life, Chrissy, and her family. Maria, her daughter, is my closest friend, and her family is now mine. Chrissy’s sons, Yianni and Nick, I also see as family.

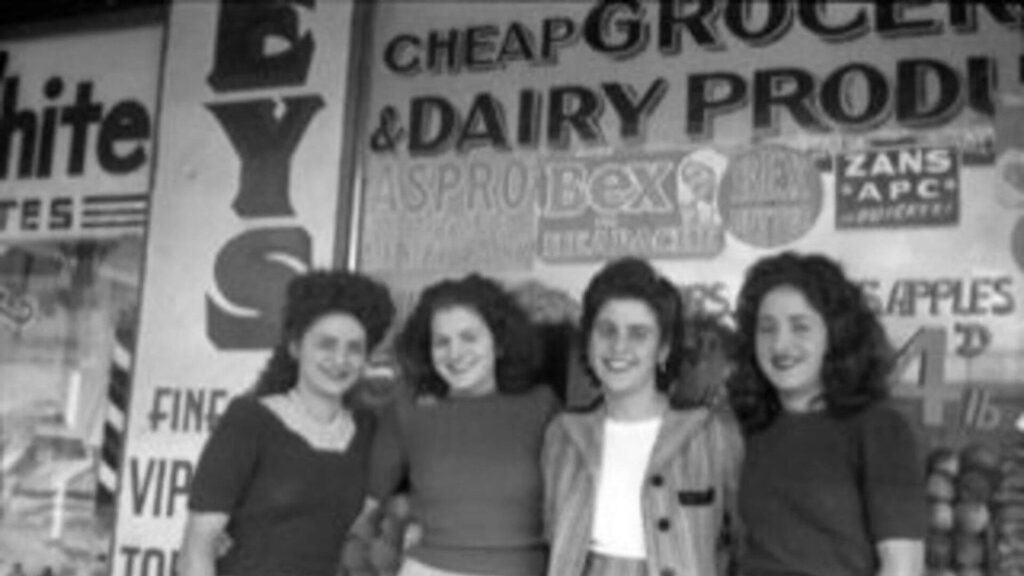

Chrissy was born on October 6, 1929, in Adelaide, as an only child of John and Aryiri Pappiannou. As a Kastellorizian whose elders arrived in the 1920s, Chrissy attended Adelaide Girls High School and became an essential service provider to the mass of new Greek immigrants.

There were no official multiculturalism or language services.

Greeks, especially the women, struggled with the language and the system, and she took the time to welcome them into her home. Chrissy’s assistance went beyond interpreting to supplying food, clothing, and other essentials. More than that, someone to talk to and to get advice about making a life in Australia.

Few people can claim to have a brand named after themselves – Chrissy could. Her father, who ventured into the tobacco business, produced a blend he called the ‘Chrisoula’.

The success of that business led him to take his wife and daughter to Melbourne in 1937 in search of more profitable business opportunities.

They returned to Adelaide shortly before Chrissie’s 12th birthday, where her father, tired of the cutthroat tobacco business, sought a fresh start and opened a fish and chip shop at the front of 75 Henley Beach Road, Mile End.

Chrissy made a profound contribution to the settlement of newly arrived Greek immigrants and did so selflessly. Her command of English, intellect, and belief in service made Chrissy unique to all of us.

Over a fence

Our connection began over a fence – on Henley Beach Road. It was enhanced at Adelaide High School and later, with Maria and Nick solidified, at Flinders University.

The often-used term blood is thicker than water, is a misconception. Bonds make families secular as well. We moulded into an extended family.

Maria became my koumbara when I married, later and my son’s nouna. We are family, and Chrissy and Kosta, her husband, who died years ago, were always my family.

Their home from the early 1970s to the 1990s in Adelaide was my home, my sister’s, and my late mother’s home. It still is.

I would hang out at Maria’s too often. We’d party, especially with her and her brothers. Their father, Kosta, loved talking politics with a snotty uni undergraduate like me while feeding me Chrissy’s finikia and baklava.

Her baklava and finikia were unmatched, and fortunately for all of us, Maria carries that tradition; she is a master in baklava and finikia.

Unlike Kosta, Chrissy was not easily assuaged by my spin and charm. Ice-cold questions like, “Aren’t you meant to be studying for exams, Foti, now?” and “Does your mother know you are here?” would see me fumble lame excuses, “Yeah, about to go home to do some work, Thea”. I’d scram.

As an adult, I spent hours around Maria’s kitchen table in Collingwood, discussing politics and society with Chrissy.

“Don’t worry about Foti; he’s very resourceful”, she’d say. To this day, that guides me through difficult times.

Pioneering and resilient

Like many Greek women of her time, Chrissy’s intellect was not allowed to flourish. The patriarchy held sway. Greek Girls did not go to university.

She would have been an erudite barrister and an even better doctor. Her exposure to medical practices while interpreting for Greek patients augmented her diagnostic skills. One doctor was so impressed that he suggested she consider enrolment into a university medical degree.

Chrissy was one of the first Greek women of her generation in Adelaide to drive, own a car, and have a mobile phone. We joked that the reason for the phone was so that she could track down her kids.

When Maria and her husband, Stavros, failed to contact Chrissy during their holidays in Greece, Chrissy sprang into action. She forensically examined their itinerary and determined they were in Ithaca; she found the number of the post office on the island, called, and provided the clerk with the absconded couple’s descriptions.

“Yes, they just left the post office”, the clerk said, “Hold on, I can see them about 100m down the road.”

By coincidence, there was a public phone near Maria and Stav as they strolled, and the postal clerk rang it. Maria and Stav picked up, “Given no one else was around,” Maria would say later.

“Why haven’t you rang?” was the first thing she heard from her annoyed mother.

Chrissy’s compassion for others led to the development of solid and lifelong friendships with many. She had a kind word for everybody and made people feel valued and welcomed. Chrissy looked for the good in people and often played the role of peacemaker.

In 2000, after Kosta, her husband, passed away, Chrissy moved to Melbourne to be with her children and grandchildren.

As a relentless worker and community-minded, she volunteered at St Vincent Hospital and the Eye and Ear Hospital until age 85.

Her children carried that spirit in professional public service, marketing, and business. In Maria’s case, she holds her mother’s spirit as a professional who assists new migrants and develops migrant settlement policies.

Chrissy was proud to see her grandchildren, Dean and Katrina – Nick’s children and Peter, Maria’s son, grow into caring young adults. She was fortunate to live long enough to catch the arrival of her great-granddaughter Mia and attend her granddaughter Katrina’s wedding in 2022.

I have no doubt Chrissy is looking at all her family now, and the many of us she helped, and no doubt with a touch of that inquisitorial capacity she had as matriarch.