One of the most important subtexts of global commodities trade in the modern era has been the central role of Greek merchants, usually, though not always, from the island of Chios, and often as not from a small, formerly highly endogamous set of families with roots in the Byzantine and Genoese nobility. While most of my focus has been on their role in moving the cotton supply chain during the American Civil War, they did similar work with grain. In fact, the Chiots’ grain skills were basically transferred to cotton and other commodities.

From the Black Sea to global markets

Today’s Russian and Ukrainian Black Sea coasts were the scene of see-saw battles between the Russians and the Ottomans in the late 1700s, and the Russians began to get the upper hand against the Turks – often enough by encouraging Balkan Orthodox to revolt to distract the Turks, though the Russians would conveniently forget us later. In any case, the Black Sea littoral and the rich black soils of the hinterland were to yield grain harvests that would only be comparable to the American Midwest several decades later, (there is a Greek story for that, too).

The Russians encouraged immigrants to Novorossiya (New Russia)—Germans, Poles, Russians, Ukrainians, and later, Jews, but also their Balkan coreligionists, Serbs, Bulgarians, and Greeks. Many of today’s Russians and Ukrainians, particularly on the coastline, are descended from this mosaic of immigrants.

While there were Greek famers, a cadre of merchants quickly established themselves in the grain trade, most notably in Odessa but also in Kherson, Taganrog, Rostov, and Mariupol with its heavily Greek hinterland – most recently ravaged by Putin’s forces. These merchants, part of a global network with relatives in various Mediterranean cities, controlled a large portion of grain supplies to Western Europe.

Commerce and revolution

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, the merchants and shipowners were separate from each other, but the merchants’ cargoes were still carried by Greek ships, primarily by fleets from Hydra, Spetses and Psara, which could also fly the Russian flag per Russo-Turkish treaties. Both merchant and shipowner grew rich on this system, and the Russians basically subcontracted their merchanting and shipping activities in the Black Sea to Greeks.

It was not just commodities that flowed, so did ideas, particularly about national rebirth. In 1814, three clerks in these merchant houses formed a secret society called the Philike Etairia, dedicated to the liberation of Greece. This organization spread through the diaspora, the Greeks’ Ottoman homelands, and among other Balkan Christians.

The Rallis legacy and the reach of Greek trade

Crucially around the same time, a remarkable move took place when one Chiot family, the Ralli, established operations in Britain, rightfully sensing that world trade and industrialization would be centered on the British Empire. This is a little known, but vital story in the history of commerce.

In 1821, the Greek Revolution began by Russo-Greeks in that same Odessa region invading the Danuban Provinces, and though this attempt was unsuccessful, the Greek Revolution took hold in the Aegean basin, bolstered by diaspora financial and volunteer support, and most importantly by militarising the fleets of Hydra, Spetses, and Psara. The merchants’ homeland, Chios, was completely massacred by the Turks in 1822, scattering the minority who survived to the four winds, and nearby Psara was also devastated.

Though these islands’ fleets never recovered their former hegemony, the merchant network, if anything, expanded because of the horrific Chios massacre, with refugee Chiots in Trieste, Marseilles, Livorno, and elsewhere channeling efforts back into the commodities business. They sought to, and usually succeeded in, controlling the entire supply chain, from purchase, to shipping, to importation, and to finance—all within the same family. By 1850, one third of all tonnage from the Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean was handled by Greek merchants, reaching 57 percent in 1860.

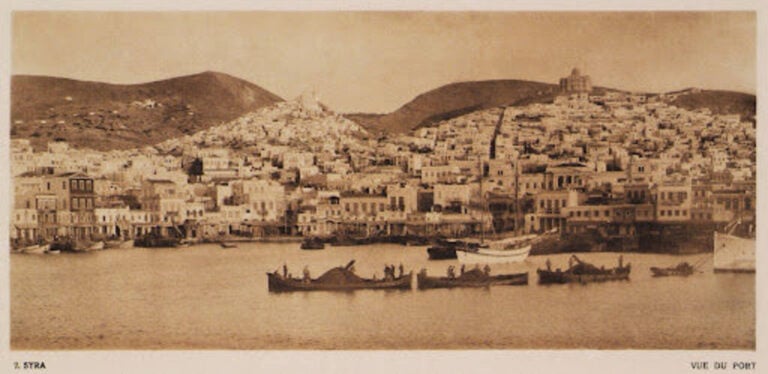

The Greeks’ prowess aroused admiration and envy. They coped, and managed, and kept their ears to the ground, investing in each other, in shipyards on the Aegean island of Syros – which became a virtual Chios in exile – and eventually in their new homelands. When Britain and France were ready to go to war to support Turkey in the Crimean War, John Ralli, the American consul in Odessa, wrote frantically to the American State Department about the opportunity for American grain exporters. That same year, the Ralli company established a New York office. Coincidence? American grain would go on to conquer the world, and here too a Greek hand guided the rudder of commerce.

The Rallis and their Chiot compatriots together with other Greeks in port or aboard ship would become princes of other commodities, most notably King Cotton, where they played a major role in the supply chain shifting because of the American Civil War, and they enriched themselves in the process.

They gave back to their communities and to their Greek homeland. Many are the institutes, schools, and interventions bankrolled by merchants. At different times, they helped to right the unsteady Greek ship of state. We might say, in fact, that the merchants helped to birth Greece.

Changes in technology, communications, and the emergence of the corporation, together with these merchants’ assimilation into their host societies, made their story gently pass into history, let the legacies are still there in descendants, in the Greek shipping families, and family pride was most recently on full display at a unique reunion of these merchant families at West Norwood Cemetery in London on September 20, 2025.

There, amid gently aging family crypts and mausoleums, descendants from the four corners of the earth met “family,” often enough for the first time.

*Alexander Billinis, is a PhD candidate in Digital History at Clemson University, and lectures in Political Science, the regular contributor to Neos Kosmos researches the role of Greek merchants in the 19th-century Atlantic cotton trade between the American South, Europe, and the Mediterranean.