Ι often wonder about the women portrayed in the old black and white photographs, trying to read in their eyes what they were thinking, as their portraits were snapped for a ticket to a foreign land.

I imagine that the horrors of the war and death they had seen as children of the Second World War, had hardened them, and it was a time when a woman’s destiny was not really her own to choose.

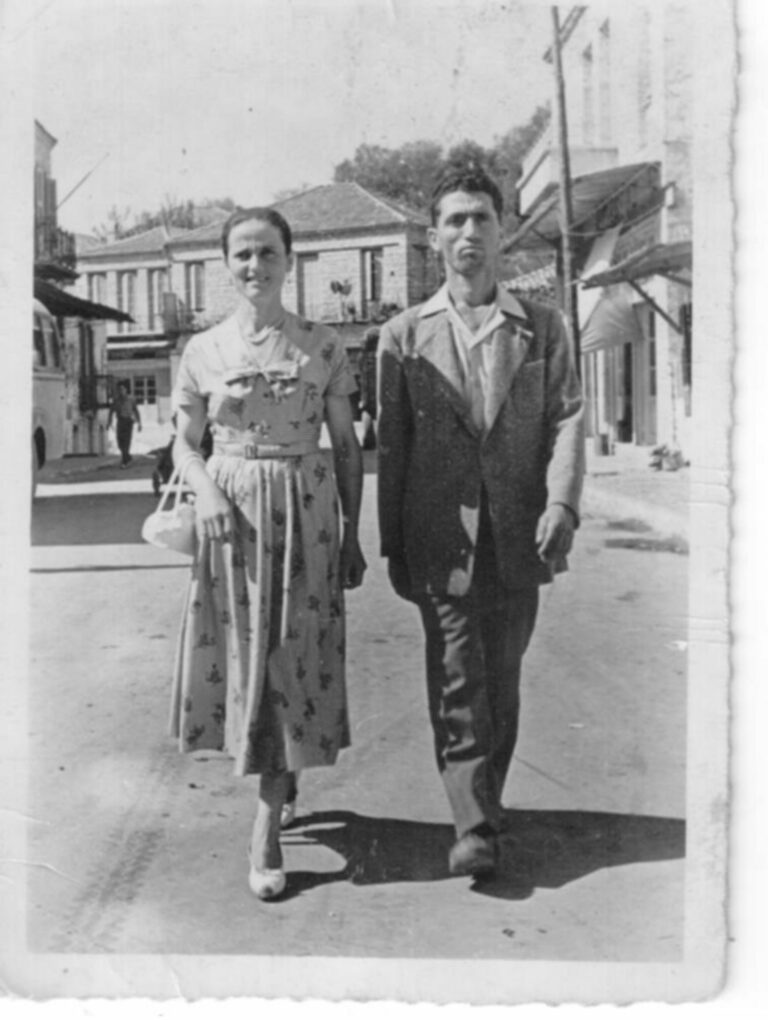

Georgia (Kamaterogiannis) Papathanasiou and Koula (Kokori) Xyna met on board the Aurelia in April 1958, leaving behind their villages in the Western part of Greece, for the first time.

In the ship heading to Australia, there were hundreds of other Greek girls and even a priest. Most were already engaged to marry someone they met once or twice, and others not at all.

Georgia was travelling to meet her brother, Nikos, and Andreas, her future husband, who she had been introduced to a year earlier, before he migrated to Australia. Koula, on the other hand, was travelling on the same ship to meet her future husband, who happened to be Georgia’s cousin.

Both motherless from a young age, Koula and Georgia leaned on each other on that journey and became lifelong friends, and as fate would have it, they would be travelling to their final resting place on the same day, 63 years later.

These two women’s lives are unique but their stories are typical of hundreds of thousands of migrants who were driven away from their homeland in the aftermath of war.

The early years, the war and depression

Georgia was born in 1926, in the tiny rural village of Taxiarchi in Aitoloakarnanía. She was only twelve when she lost her mother. A hard life became even harder as she took charge of the household and care of her younger brother. When World War II broke out, fear would become another constant. She saw people shot, hung. Many times she could hear their cries in her head even after they had died.

She herself had narrowly escaped when she came face to face with enemy soldiers, her children recall, and she never forgot seeing a mother shot in the arm while breastfeeding her baby.

Koula was born a few years later in Evinochori, into a family of eight children, and though she never knew her mother, who died when she was only 2 months old, her childhood memories were happy ones.

It was not a life of excess, but a rich one made so by gatherings of friends and family. Her family home had a well, and so, many people would gather there at all times of the day. She often told her children that there scarcely was an evening when a guest did not sit at their table or stay overnight before continuing on their journey the next morning.

The years of the second world war and the civil war brought hardship. Relatives from Athens saw this period out in her father’s household in the village

Just after the war, a traumatic event would remain with Koula for the rest of her life.

“When the Italian and German soldiers left, the villagers gathered all the unspent mines and piled them by the river in her town. The soldier who was on guard, must have been bored. And he was just firing off into the distance and a bullet ricocheted and instantly killed her friend Panagioti, who was just next to her. She would often wonder ‘Why did I live and why did Panagiotis die?'” Spiridoula, her daughter tells us.

After her father died she was pressured to migrate, and marry in Australia.

“The migration process was hard for my mother,” Spiridoula continues. “I think because it wasn’t really her choice to come out here. Like a lot of women of that era, the decision was made for them.”

There was only one thing she had ever asked for herself. Which was to return to her homeland when she died.

Spiridoula says she felt at peace, when her mother was being lowered into the ground, close to her childhood home in Greece.

“I felt that she was 500 metres from where she grew up. I think that because her mum died when she was just two months old, she always had a longing for something that was absent. And in her mind she just wanted to be there. It was the only thing that she requested that was completely self referential. Every other decision or thing that happened in her life was decided by others. Firstly by her brothers, who decided for her to come out here, because they had lived through the Second World War and the depression. They had four sisters, only one of which was married, and they must have been nervous that they were going to have three unmarried sisters to look after.”

The journey, and settling in Australia

Recently, before her death, Georgia recalled Koula’s anguish as they were reaching the port of Melbourne.

“You have your brother, Nikos, waiting for you at the port, but me.. where am I going and to whom?”

They lived together in that first chapter in their new lives, the two couples, along with siblings sharing a house, before the children arrived. This was a time when important lifelong relationships were formed that were expressed through koumbaries.

Working and caring for their children – Women helped each other to get by

When Georgia first arrived in Melbourne, she desperately wanted to find work.

Once, after hearing that a factory was hiring, she would travel out of town every day, for the next 42 days, hoping to get hired. On arrival the ladies would be given a number and asked to wait until they were called. Many numbers weren’t called, and those women were asked to come back the next day. Georgia did this for seven weeks before she gave up.

As work didn’t come in, the mums in the neighbourhood would ask Georgia to look after their kids, so they could go to work.

She would look after four children at a time, along with her own. She had a jar on top of the fireplace, and the women would put 2 shillings, or if they didn’t have that amount, anything they could afford. Over time, she looked after a total of 76 children, and never forgot their names.

Just before she fell pregnant with her seventh child, Georgia finally found work at a sewing factory making quilts.

She hid her pregnancy from her workplace, afraid she would lose her job, and returned back to work only 40 days after giving birth to her youngest child.

“My parents had to make ends meet to pay the bills, for us, the schools, and she needed the work,” her daughter, Maria, told us.

Georgia’s job was labor intensive and very difficult. There were periods of time where she would cry every day. She spoke of regularly piercing her fingers on the machine hooks and the blood she and the other workers would spill on the factory floor.

She would wake up at 5 in the morning to prepare school lunches and sometimes an evening meal before waking the children and leaving for work.

She would get home around 5pm, and if her eldest, Maria, who was only 9 at the time, hadn’t cooked dinner, Georgia would. Then she would bathe her children and put them to bed before spending hours tending to household duties and washing the entire family’s clothes by hand. This left her with very little time to rest.

In the factory where she worked there were many newly arrived migrants. Italians, Greeks, Yugoslavs, Turks. She made friends, and they looked out for each other. Sometimes when she was so tired, they would tell her to lie down and sleep during the breaks, whilst they covered for her.

From them she would learn how to sew, knit, crochet, and discover new recipes. “She’d see a pattern and she’d pick it up straightaway.” Maria said.

Though she had little education, she picked up where she had left off when her children started Greek school, and became an avid reader.

She was interested in finding out about natural cures, and many people would come to her for advice.

The husbands of both Georgia and Koula worked night-shifts or around the clock

Before they set up the Albert Park Deli, Koula’s husband Vassili was initially a baker, and his work was a 24 hour cycle. He would start at four in the afternoon, make the bread, deliver it and then come home mid morning before he was off again after a few hours of sleep.

“My mum had to tend for four kids on her own, it wasn’t easy. She would have been quite lonely too, as they were living in Essendon, where there were not many Greeks,” Spiridoula says.

Georgia was also very involved in her children’s learning, and tried to help them with their homework, even if it was at times, beyond her.

“She always encouraged us to better ourselves,” her daughter Rini says. “She would come to all the Parent-Teacher interviews. She also put her three sons into Scouts, as she wanted them off the streets, and she would be the one to take them there by bus.”

Georgia returned to Greece for a holiday only once, whereas Koula and her family had tried to repatriate in 1976.

“It was a very important time in our family’s existence, because it was the first time we met our extended family, and a grandmother. As children of migrants, I used to look at my Australian friends and think how great it would be to have a house that belonged to previous generations or somewhere where family could congregate across generations,” Spiridoula said.

“Our parents, our family friends they were all preoccupied, trying to get food on the table for their children, and we didn’t have the grandmother’s touch, you know, the way grandparents relate to their grandchildren. We didn’t have that source of affection, That feeling of stability that extended family gives you.”

“Meeting the extended family in the villages they grew up in, I was able to understand them better. It was a miracle really, that they were able to adjust at all to Australia. Can you imagine their gaze getting off the ship? They came from a rural environment to an urban one, let alone the cultural differences, the distances. They were heroes really.”

The wisdom they gave

“When her mother passed away, aunty Georgia was only 12 years old, yet she instantaneously became the glue that kept her family together. Her father and my dad,” her nephew, Arthur, says.

“As life continued, with marriages, children, grandchildren, and the clan became bigger in a strange foreign land, aunty Georgia stood out as the only person for advice and guidance in all aspects of life. She would also settle arguments, about tradition, scripture, you name it. Her presence was always felt when you entered a room, yet she was the quietest person there.”

“People trusted her with their innermost secrets”, Dimi, Georgia’s daughter told us. “My mum knew stuff about other people that she never told a soul.”

Spiridoula was grateful to know from the priest of her mother’s church, from someone outside the family that is, that her mother had been happy.

“I just wanted to be able to provide for her what she wanted, without her having to ask.”

Maria also says that they could see sadness in their mother’s eyes, sometimes, and they strove to make her smile.

But for Georgia and Koula, seeing their children around them filled them with joy. The family that grew, with grandchildren and great grandchildren gave them solace and pride.

They kept in touch with each other throughout their lives, and the families met and celebrated together on many occasions.

Though Koula passed away a year before Georgia, it was on the same day of the same month that they travelled to their final resting place, in September last year.

Georgia to join her beloved husband, Andreas, who had died only a couple of months before, her brother and father in Fawkner Memorial Park, and Koula on her way back to Greece, with her children, to be buried in her homeland.

Georgia was my aunty who always had a comforting piece of advice for me when I settled in Australia a few years ago. Her gentle kind nature reminded me of my own grandmother in Hungary, who was born in the same era and saw her dreams collapse from the impact of war.

Givers to a fault, these women, as so many more of this generation, though oppressed, strove to better the world, planting the seed for their children and grandchildren to grow, and find their place in the future of Australia.